"At the midpoint of fluorescence and dripping lies effluvium": A Chat With Isaac Fellman About Archives and Vampirism

Recently I had occasion to chat with my pal Isaac Fellman (of Isaac’s Law) about Dead Collections, his latest novel released earlier this week. Here’s a condensed version of our conversation (if you boil the conversation gently for three hours, you’ll end up with dulce de leche).

Danny: Can I ask you for a brief précis of the book before we get into the more abstract questions of attachment and and archives. What’s your (indoors-only-to-avoid-sunlight) elevator pitch?

Isaac: So vampires and archivists both hate sunlight. It will kill a vampire, and also a manuscript. Vampires and trans mascs both have problems with medical stigma and looking younger than they do. As for what trans mascs and archivists have in common, it’s a subscription to this newsletter. Dead Collections is about all of these conditions colliding, in the form of a wretched but gleeful man who is secretly living at his basement job. Basically, the book is a love story about how this vampire archivist (Sol) gets a donation offer from the widow (Elsie) of his favorite TV writer, and the two of them rapidly realize that they’re in lust with each other, not least because Elsie also has a lot of gender stuff to unpack. How can they convert their horniness into something lasting? How can Sol use archival cataloguing and processing to set the writer’s unhappy ghost to rest? Also, how can I convey the feeling of working with archival materials through multiple pastiches, vividly described smells, and a scene where the ghost makes a guy’s packer shrivel up?

I started writing this in January of 2020, after a co-worker told me an anecdote about a donor who complained that "the vampire archivists" were too enthusiastic in their work. Calvin Kasulke told me I had to write this vampire idea, and the book is a little bit a tribute to Calvin's Several People Are Typing; it’s also a little bit about my undimmed ardor for Ling Ma’s Severance. Confessions of the Fox is in its DNA too, in that it’s a book about a trans man having an ultimately productive emotional breakdown and thinking about tits.

Danny: Talk to us about your vampires! No two sets of fictional vampires are alike — what rules govern yours?

Isaac: I love that phrasing. It's true — one of the ways you know you’ve got a vampire on your hands is that they have rules, despite their popular image of lawlessness.

My book has sort of a kitchen-sink drama take on vampirism: it’s defined by its daily grind. Sol has to have his blood cycled every week in a rundown clinic. His body’s functions are slow, and his medical transition has more or less come to a halt, even though he’s still taking his hormones. Any hint of sun will kill him instantly, and he lives in a world that doesn’t care to provide accommodations for his basic safety, so he lives in constant fear of an early death. He’s always getting caught out and hiding in basements, in subway stations, in café bathrooms with toilet paper stuffed under the door.

I wanted to engage thoughtfully with the idea of vampirism as a chronic illness that needs to be managed. I'm wary of presenting a literal monster as a metaphor for a marginalized experience, which was why it was important to me that Sol's vampirism isn’t a metaphor for anything; it's just something difficult that he has to go through, and which other people regard with a combination of stigma and desire. (I mean, I'm slightly lying about the metaphor part — there are obvious parallels between his vampirism and his transness — but I've tried to use them to comment on each other, rather than have one stand for the other.)

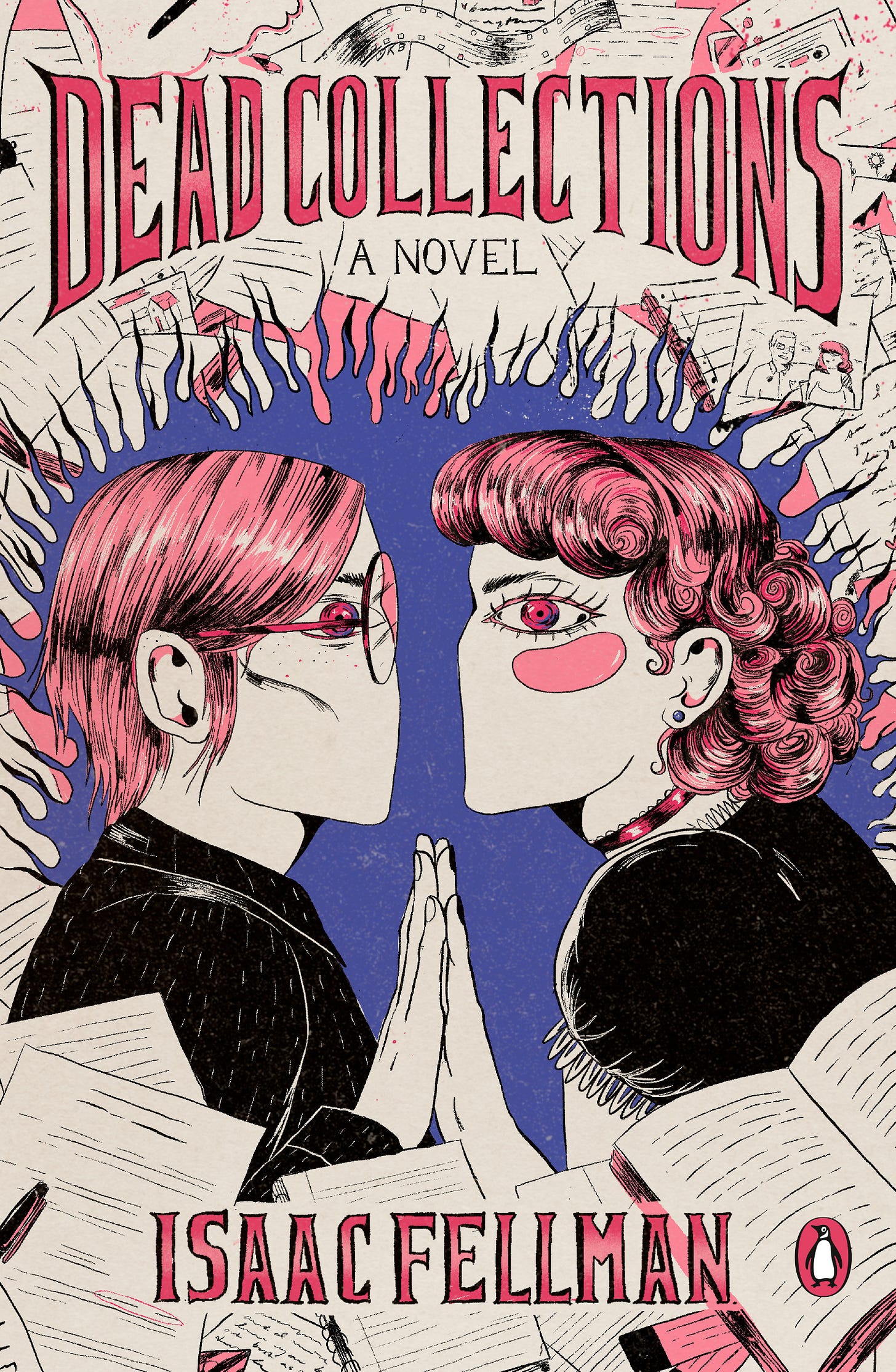

Danny: I don't know many novelists (outside of one or two big-name outliers) who have any more input over their books' covers than what you get at the eye doctor ("Which of these three similar options do you like least?"), but you successfully lobbied for Evangeline Gallagher to illustrate Dead Collections. How did that come about?

Isaac: Yes... “Is 1 or 2 better? How about 3...or 4?” My editor at Penguin asked me to send suggestions and reference images for the cover. I have no idea how common this is, but I think it helped that people don't have a clear idea of what archives look like. It's tough to nail down an “archives vibe” unless you’re going the Grimoire route, which wouldn’t be suitable for a book like mine, which is about a modern collection.

Archives are actually atmospheric in a very un-Grimoire way: fluorescent-lit, anonymous, yet suffused with a kind of dripping paranoia from the sheer awareness of how much deeply personal stuff is all around you. I’m a comics fan and pay attention to illustrators. To convey the feeling of archives, I immediately thought of Evangeline, whose work has a similar sense of paranoia, combined with big, tidal queer emotions suitable for a love story. The piece I linked them to was “Setting Each Other On Fire,” to which the finished cover owes some of its vibes (and a print of which is on display in my oddly-horny kitchen). The characters in this piece have been through it, and are in a state of high emotion. They've arrived at the brink and cruised each other there, and I think the book designers were like, “Yes! That’s Isaac's book! The spirits [Isaac] did it all in one night!”

Danny: It feels very Isaac that a book you’ve described as fluorescent and dripping with paranoia (accurately, I think) recently made it onto a Good Housekeeping list of best romance novels for "get[ting] you in the mood." What's the mood, Isaac?

Isaac: Fluorescent yet dripping, Daniel!

No, like — it’s a book about how a crush can mean a lot of things, and one of those things is change me. We can get crushes because people are hot, or because they know just how to tease us, or because we’re excited about the idea of love, but the ones I’m most interested in are the crushes we get because the way someone lives their life unnerves and excites us. My archivist hero, Sol, is depressed and grieving the time when — pre-vampire — he could go outside without dying, and his transition felt like it was going somewhere. It’s a frozen grief. His future partner, Elsie, steamrolls in with a burning grief — for a dead wife and a youthful sense of possibility, including possibility about gender. These two are perfectly positioned to shake each other's bones, and also to jump them. They are going to challenge each other’s assumptions about what a good life means. They are also going to have unwise sex at dawn in a movie theater projection booth. The mood is “recognition that in decay there is rebirth.” The mood is “we are forty and making the mistakes we were supposed to make at twenty-five, but didn’t, because we thought we could avoid loss by cultivating poise and resignation.” The mood is “I want you to destroy me, mostly in a fun way.”

Danny: At the midpoint of fluorescence and dripping lies effluvium. Archivally apropos!

You’ve talked elsewhere about the way the unpredictability of archival work can destabilize or postpone significant life choices like transition and "at a time when many of our friends are settling down, we’re being stirred up like fallen paper and scattered to the winds," which seems particularly true of Sol upon meeting Elsie.

In some ways, this feels like an answer to a question you posed in that same piece: “Should the privilege of unattachment determine whether a person can become an archivist?” You said no on both occasions, of course, but at greater length in Dead Collections, and without giving anything important away I think I can say the book is particularly interested in how archival work can incorporate attachment rather than holding it perpetually in abeyance or swallowing it wholesale. I imagine that has something to do with the way Elsie engages “possibility about gender” that doesn't look like replicating Sol's own transition.

Isaac: Damn, Danny...you dug up a blog post I did for my professional association in 2019? This is advanced stuff.

Danny: “Dig up” is a little strong, maybe, but I did read it. I can no longer remember who the woman was, nor what outlet the interview was for, but sometime around 2012 I was tasked with interviewing this writer (I want to say she was a biographer?) who just blitzed through the questions I’d written down in about eight minutes, because I’d wrongly assumed she’d fill in any possible gaps in the conversation or that some of the questions might lead her to bring up related topics, and then she got very sharp with me when I admitted I didn’t have any more questions for her. So ever since then, before I interview anybody, I like to go through their other interviews in the last few years, as well as the first few hits from a basic Google search, just as insurance.

Isaac: I feel like we’re talking about two different kinds of attachment. One is the attachment that makes it hard, practically speaking, to go into an unpredictable field like archiving. I have a permanent job now, but it sits on top of a pile of temporary or untenable jobs — ones that were easier to string together because I was literally unattached (divorced, childless, without family to support).

Then there’s the kind that's at the heart of your question — emotional attachment, un-objectivity, love. Archivists talk a lot these days about the illusion of neutrality, how we need to stop pretending that we don’t bring our biases, traumas, and personal histories to our work. It’s good that we’ve internalized this, because for a long time, the idea of neutrality really was central to our field. That said, I don’t think we’ve figured out what to replace that idea with. The old idea of the archivist as transparent eyeball is too central to our thinking, even though we know it’s wrong.

I didn’t write this novel to chart a new course forward for my field, but I do think Sol’s story has been useful for me as an archivist. He has a lot of obvious professional vices: he’s highly emotional in his approach to the work, he projects himself into the collection, he gets lost down rabbit holes. But what if we consider those vices as attempts to create an ethos of non-neutrality? What if Sol’s willingness to pick up vibes, to make good guesses, to be sloppily honest at inopportune times, are the beginning of a new and useful kind of thinking?

Danny: Fan fiction is a very literal inheritance here – boxes and boxes of a dead woman’s investment in fandom make its way to Sol's office where he has to figure out how best to dispose of/preserve/catalog/interpret it, to say nothing of his subsequent relationship with her widow who delivers said boxes. There’s a funny, shared lack of futurity between Sol’s transition and this inherited tradition. His transition is externalized and stalled at the same time, out but not “finished,” present but also sort of impossible, and sometimes seems fully alive and sometimes inert. It struck me, on rereading, that there's a complex engagement with the idea that transition is like death, as it’s been so often described ("It feels like someone died," etc) – that you've taken this idea both literally and seriously, and sought to envision what kinds of existence are possible once the question of life and death has been settled. Is this a reading you’ve expected? One that surprises you? One you disagree with? Circle yes/no/maybe.

Isaac: I didn't expect that reading, and it surprises me, but I don't disagree! Some cis people do see trans people the way they see dead people. Our perspective is unimaginable. Our interiority is inconceivable. Nobody can think about us without imagining “it” happening to them, and how they're sure they would feel if it did. The things that happen to our bodies don't bear thinking about.

I suppose I connect that to the way I felt before transition: as if I’d been assigned an inviolate body to maintain in perfect condition forever. Embracing transition meant embracing the cycle of degradation and resurrection that’s essential to life.

So, sure, why not take literally the idea that trans people are dead? Why not ask, well, if we're dead, what new life do we feed and sustain? It wasn’t something I meant to put into the book, but it’s the kind of thing that’s always in the back of my mind.

Danny: The first time I read Dead Collections I was surprised to realize I was as invested in the development of Sol’s relationship with his work enemy/begrudging comrade/Ahab, Florence, as I was in the development of his romantic relationship with Elsie. (Well, maybe not surprised; I love thinking about having an enemy.) It’s a very textured relationship, and a highly mediated one – some of their mutual aggression is explicit and avowed, lots of it is indirect and filtered through HR, and there’s a slight but definite sense that just below the surface is a good old-fashioned identity politics brawl eager to bust out and bust up. Did you find Sol and Elsie’s relationship at all connected to Sol and Florence’s? Or did they feel distinct as you wrote them?

Isaac: Florence was a character who snuck up on me. She really made herself known during edits, when I took Calvin’s advice to make her 20% worse in every way, and also changed her from a younger femme to an older butch; she was always fascinated and horrified by Sol's transition, but it wasn’t always this personal, which seems bizarre to me now.

Sol is surrounded by three people who are refusing to imagine transition. All of them project their anxieties onto him. Florence is proud to be a butch lesbian, and Sol’s existence feels invalidating and spooky to her. Elsie is an old-school femme whose pride in femininity disguises a sharp desire to experience every gender at once, and who is inspired by Sol to become something totally different from him. And the late Tracy, the TV writer — and, I’ll go on record here, the only one of the three who is a trans man per se — never knew Sol at all, but is reaching from beyond the grave to ask for his help.

I definitely see all of them as parallels to each other. They each have their own reason not to examine their gender, and I think Sol helps all three of them in different ways. This doesn’t mean Sol and Florence aren’t enemies; she does very badly by him, and he’s failed her too, and they’re not going to come out of this buddies. But I think knowing Sol helps her to realize what kind of asshole she wants to be, and maybe what kind of woman.

Exeunt.

"Embracing transition meant embracing the cycle of degradation and resurrection that’s essential to life." I've been thinking about this a lot lately. Gender-affirming surgery, though I want it, also feels like a kind of death -- at least to some of my past selves. (Oh no, is my inner child a TERF?) Transitioning during the pandemic makes death an unavoidable concept and also curiously liberating when I stop running from it.