“But,” said Grimaud, in the same silent dialect, “we shall leave our skins there”: What's Going On With The Sign Language in "The Three Musketeers"?

Help me out, French history experts...

I hesitate to ask “Why is no one talking about this?” because that’s a surefire way to look like ignorant. Almost certainly someone has talked about this, and I just haven’t gone about looking for it in the right way — so I must call upon you, my readers, in the hopes that some of you know more about Alexander Dumas and the history of sign languages in France than I do.

You’ll remember that I’ve recently been reading Dumas’ The Three Musketeers, and I’ve been struck by how often the book makes reference to sign language — often in a complicated and formalized way. There are plenty of scenes during military or espionage missions where one character will quickly sign to another to follow them, or to keep silent, or to keep watch — but there are even more instances where there is no obvious or expedient “need” for silence, where the signs serve interpersonal or social purpose.

I thought there’d be plenty of articles or dissertations on the subject. And maybe there are, and I’m just employing the wrong search terms!

The two characters who most frequently make use of signs are Athos, the oldest Musketeer, and his manservant Grimaud:

“Athos, on his part, had a valet whom he had trained in his service in a thoroughly peculiar fashion, and who was named Grimaud. He was very taciturn, this worthy signor. Be it understood we are speaking of Athos. During the five or six years that he had lived in the strictest intimacy with his companions, Porthos and Aramis, they could remember having often seen him smile, but had never heard him laugh. His words were brief and expressive, conveying all that was meant, and no more…

His reserve, his roughness, and his silence made almost an old man of him. He had, then, in order not to disturb his habits, accustomed Grimaud to obey him upon a simple gesture or upon a simple movement of his lips. He never spoke to him, except under the most extraordinary occasions.

Sometimes, Grimaud, who feared his master as he did fire, while entertaining a strong attachment to his person and a great veneration for his talents, believed he perfectly understood what he wanted, flew to execute the order received, and did precisely the contrary. Athos then shrugged his shoulders, and, without putting himself in a passion, thrashed Grimaud. On these days he spoke a little.”

All of the Musketeers, and D’Artagnan too, thrash their manservants (or talk about the importance of thrashing your manservant early on in the relationship, to make sure he respects you) throughout the book, so there is nothing unusual about this aspect of Athos’ relationship with Grimaud. The silence is unusual, that is to say, not its violent enforcement. And while the story does reference Grimaud’s occasional misreadings of his master’s wishes to comic effect, for the most part the two are shown understanding one another remarkably well without speech.

During one episode, where D’Artagnan appears unexpectedly at Athos’ apartments wearing his mistress’ clothing after fleeing from some enemies, “Athos made [Grimaud] a sign to go to D’Artagnan’s residence, and bring back some clothes. Grimaud replied by another sign that he understood perfectly, and set off.”

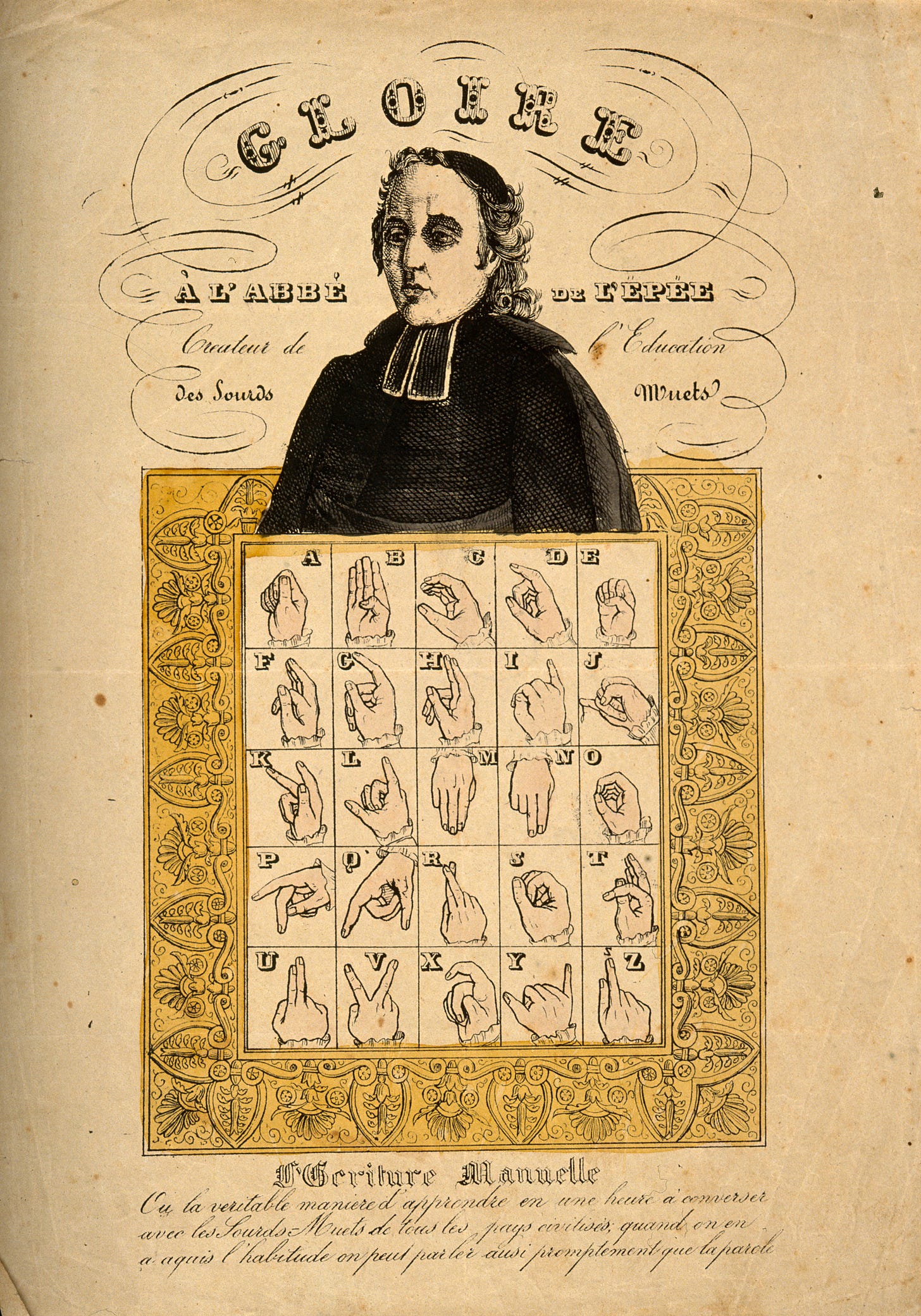

I have a very cursory understanding of the development of sign language and Deaf history in France — I know that the Abbé de l’Épée began learning from a Parisian group who used sign language in the mid-18th century, and that a few decades later the Deaf bookbinder Pierre Desloges published Observations of a Deaf and Dumb Man on An Elementary Course in Education (which is available on Project Gutenberg).

But I have no idea how familiar Dumas might have been with any of this. His own father, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, became partially deaf after imprisonment and an assassination attempt in 1801 — but since he died when Dumas was only three or four, I have no idea how much this might have affected his family.

I know too that a number of monastic orders developed types of signing systems in the medieval period, usually for the purpose of observing the Great Silence, some of which were “gestural” (without grammar or other features of a distinct language) and some of which involved finger-spelling. Many of them were quite complicated:

These are the signs of the books that one shall use at the divine service in church.

When you would like a gradual, move your right hand and crook your thumb, for this is how it is denoted.

If you would like a sacramentary, then move your hand and make a motion as if you were blessing.

The sign of the epistolary is for one to move his hand and make the sign of the cross on his forehead with his thumb, because one reads the word of God there as well as on the Gospel-book.

When you would have a troper, then move your right hand with your right forefinger turned forward toward your breast, as if you were using it.

If you would like an oblong book, extend your left hand and move it, then set your right (hand) over your left arm the same distance as the length of the book.

But curiously enough, the Musketeer who is preparing himself for a career in the Church, Aramis, almost never employs signs, either with his manservant Bazin, or with any other character. It’s Athos, the aristocrat living in semi-concealment, who uses it most. Sometimes their use of signs reads like an extension of Athos’ aristocratic authority over Grimaud, his total mastery of Grimaud’s body and behavior:

“On their way they met Grimaud. Athos made him a sign to come with them. Grimaud, according to custom, obeyed in silence; the poor lad had nearly come to the pass of forgetting how to speak.”

But while in certain moments it’s depicted as a patrician whim, at other times his reliance on signing is associated with depression or melancholy; Athos is sometimes so overwhelmed he finds speech impossible:

“And yet this nature so distinguished, this creature so beautiful, this essence so fine, was seen to turn insensibly toward material life, as old men turn toward physical and moral imbecility. Athos, in his hours of gloom—and these hours were frequent—was extinguished as to the whole of the luminous portion of him, and his brilliant side disappeared as into profound darkness.

Then the demigod vanished; he remained scarcely a man. His head hanging down, his eye dull, his speech slow and painful, Athos would look for hours together at his bottle, his glass, or at Grimaud, who, accustomed to obey him by signs, read in the faint glance of his master his least desire, and satisfied it immediately.”

Some of the other signs between Grimaud and Athos are described, if sketchily, while others seem remarkably abstract [emphases mine]:

“Grimaud no doubt shared the misgivings of the young man, for seeing that they continued to advance toward the bastion—something he had till then doubted—he pulled his master by the skirt of his coat.

“Where are we going?” asked he, by a gesture.

Athos pointed to the bastion.

“But,” said Grimaud, in the same silent dialect, “we shall leave our skins there.”

Athos raised his eyes and his finger toward heaven.

Grimaud put his basket on the ground and sat down with a shake of the head.”

“D’Artagnan dressed himself, and Athos did the same. When the two were ready to go out, the latter made Grimaud the sign of a man taking aim, and the lackey immediately took down his musketoon, and prepared to follow his master.”

Athos recognized Grimaud.

“What’s the manner?” cried Athos. “Has [Milady] left Armentières?”

Grimaud made a sign in the affirmative. D’Artagnan ground his teeth.

“Silence, D’Artagnan!” said Athos. “I have charged myself with this affair. It is for me, then, to interrogate Grimaud.”

“Where is she?” asked Athos.

Grimaud extended his hands in the direction of the Lys. “Far from here?” asked Athos.

Grimaud showed his master his forefinger bent.

“Alone?” asked Athos.

Grimaud made the sign yes.

“Gentlemen,” said Athos, “she is alone within half a league of us, in the direction of the river.”

“That’s well,” said D’Artagnan. “Lead us, Grimaud.”

And it’s not only these two who speak in signs, even in signs which communicate fairly complicated ideas. Nor is signing always enforced from the top down as an indicator of dominance: The Queen of France signs to her women and to D’Artagnan; Aramis makes a sign to D’Artagnan in an early chapter “to keep secret the cause of their duel,” while D’Artagnan later makes a sign to the Musketeers “to replace in the scabbard their half-drawn swords.” D’Artagnan interprets signs from his landlord (a serious social inferior), his landlord’s wife, Cardinal Richelieu, a poor and elderly stranger, and Lord de Winter.

It’s all over the story! And I’ve been able to learn so little about it, about whether Dumas might have had a particular signing tradition in mind when writing the book (or, for that matter, his ghostwriter Auguste Maquet, about whom I know almost nothing, or Gatien Courtilz de Sandras’ Memoirs of M. D’artagnan, on which The Three Musketeers was based, and about which I know even less).

So: do you know anything about Alexandre Dumas, French early modern history, 17th or 19th-century literature, or the history of French sign languages? And if so, can you shed any light on what might be going on here? I’m terribly curious and I rely on you to help cure me of my ignorance.

Like Lord de Winter, I fill two glasses and by a sign invite you to drink with me…

[Image via]

I’m sorry I can’t help you directly, but I wanted to let you know that there’s another instance of Dumas sign language in The Count of Monte Cristo, which I am currently reading and listening to in French. The young woman Valentine uses a sign-based language with her grandfather M. Noirtier, who is paralysed from the neck down following an illness, but is able to blink to indicate yes and no. A lot of it seems based on using intuition and context to enable Valentine to frame the correct closed questions. For more abstract issues, a dictionary comes into play. There’s also a reasonably long scene describing how M. Noirtier is able to dictate his will to a notary using blinking and a dictionary. Valentine’s lover promises to learn her sign language so that he too can communicate with her grandfather and take an active role in caring for him. This really confirms Dumas’s interest in sign-based languages generally and how people can communicate when speech isn’t possible.

I love this! I have been reading the D'Artagnan romances this year, also, and really enjoyed this piece. Even if you never get to the bottom of it, I feel like my reading experience has been enriched.

I wonder if it might just or also be indicative of Athos' refinement, his aristocratic mien, that he is able to communicate such complexity with such subtlety, and indicative of Grimaud's "quality" as a lackey (not sure what translation you're reading - mine repeatedly refers to Grimaud, Bazin, et al as 'lackeys') that he is able to interpret it. They are beyond a marriage - the aristocrat and manservant. They don't finish each others sentences, they know them with out saying them. Additionally, I felt like the silent communication was being used to a comic effect; its so overdrawn (i.e., "we shall leave our skins there") that it might be meant to draw a laugh?

I would like more thoughts on The Three Musketeers, please.