Kafka's Metamorphosis But The Other Samsas Are All Empaths

Previously: I am the horrible bug that lives in the town. I am the bug and you are the miserable mother with no antennae. I invented my body and it was the worst idea.

As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect. He was lying on his hard, as it were armor-plated, back and when he lifted his head a little he could see his dome-like brown belly divided into stiff arched segments on top of which the bed quilt could hardly keep in position and was about to slide off completely. His numerous legs, which were pitifully thin compared to the rest of his bulk, waved helplessly before his eyes.

What has happened to me? he thought. It was no dream. His room, a regular human bedroom, only rather too small, lay quiet between the four familiar walls. Gregor’s eyes turned next to the window, and the overcast sky — one could hear rain drops beating on the window gutter — made him quite melancholy. What about sleeping a little longer and forgetting all this nonsense, he thought, but it could not be done, for he was accustomed to sleep on his right side and in his present condition he could not turn himself over. However violently he forced himself towards his right side he always rolled on to his back again. He tried it at least a hundred times, shutting his eyes to keep from seeing his struggling legs, and only desisted when he began to feel in his side a faint dull ache he had never experienced before. As he struggled again to rouse himself, he tilted too far across the new axis of his thorax and clattered noisily to the ground. All at once there came a knock at his bedroom door.

“Gregor,” his sister Grete cried from the hallway, “I am a highly sensitive person, with a keen ability to sense what people around me are thinking and feeling, an ability that is so keen within me, in fact, that it operates as both superpower and chronic disease. I can tell that you’ve turned into a giant bug in there, and that you have a terrible pain in your side, and that you’re worried about work, and family rejection, and that you want to eat garbage, and it’s as if it’s happening to me, too.”

“Just a minute,” Gregor said, lumbering his many little legs in what he hoped was a consistent direction doorwards. “I’ll be up at once. The life of a traveling salesman may be difficult, but it’s nevertheless the life I’ve chosen, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

“I know how hard you work to support this family,” Grete said, weeping a little. “I can sense it, because of my great empathy, so in a way I work as hard as you do to support this family, because of how keenly I can sense your hard work, which is very tiring for me.”

“How distressing that must be,” Gregor jawed.

“Oh! Oh!” Grete said. “My jaws! I can feel them alive with mandibular clackings and re-settings — as if my entire anterior skull has been rearranged along horizontal lines for the purposes of grasping, crushing, and grinding. How monstrous!”

Gregor heard the sounds of additional footsteps in the hallway, and moments later his sister’s voice was joined by that of his mother and father, high and pinched with empathy.

“Oh, Gregor,” his mother wept. “I often feel deeply tuned into the feelings of those around me, even people I don’t know well. I suppose you could describe me as exceptionally sensitive, but of course it’s more than mere sensitivity, or even receptivity. Think of me as a sponge, which absorbs the emotional conditions of others without differentiation and without protection from the energies that others give off. I myself do not give off anything. It is a terrible gift, this empathy of mine, and I cannot help but experience your enweevilment as a psychic assault. Against your experience I have no defense. I am being horribly transformed! I am being metamorphosized!”

“So too am I being metamorphosed,” said Gregor’s father. “All through the night last night was I troubled by intranquil dreams, dreams that rearranged my soft innards into chitinous spinnerets and agglutinated scales, and when I woke, it felt as though my numerous legs, which were pitifully thin compared to the rest of my bulk, waved helplessly before my eyes. There are thirteen signs that a person might be an empath, Gregor — empaths are vanishingly rare, but I count myself one of them — we experience things differently than other people, and can even sense someone else’s pain or even their intentions, without ever meaning to. One sign is that you take on other peoples’ experience as your own. Another is a deep sensitivity to vibes. For example, an ugly or cluttered room is not merely distasteful to me, but the source of profound spiritual and physical pain.”

“So too did my numerous legs feel pitifully thin compared to the rest of my bulk,” Gregor’s mother said. “So too are they waving helplessly before my eyes, even now, and sometimes people turn to me for advice, because empaths make exceptionally good listeners, although that sometimes means that other people don’t realize how much energy it takes for me to listen and advise them, and how important it is for me to recharge after I have shared my gift with them.”

“As an empath,” Grete said, “the mere idea of pain or violence completely incapacitates me. I am completely incapacitated by your verminity, Gregor. I am beset by ridges, and I feel too swollen to even hide under the sofa.”

“All I need,” Gregor’s father said, “is for someone to bring me a whole selection of food, all set out on an old newspaper. Some old, half-decayed vegetables, bones from last night’s supper, perhaps covered with a white sauce — one that has thickened, of course, if the sauce has not thickened than I shall not desire any sauce at all — some raisins and almonds, a piece of cheese that I would have called uneatable two days ago, a dry roll of bread, a buttered roll, and a roll that has been both buttered and salted, for the purpose of comparison, and besides all that, a basin full of water that is to be reserved for my exclusive use, and for the creature who brings me my nourishment to understand with fine and innate tact that I cannot eat in their presence, and so to withdraw quickly, even turning the key, to sensitively and indirectly communicate they understand the importance of my taking my ease, as much as I like.”

“Yes,” Gregor’s mother said, “That is exactly what I need, too, for I have been turned into a horrible sclattering sort of creature, and besides I am in exquisite agony from when the chief clerk at my traveling-sales office threw his shoes at me this morning, because I was late for work, on account of having been crittered in my sleep.”

“Oh, Gregor!” Grete moaned. “If only you could open this door, and see how much we are bugs now, I am persuaded that you would take pity on your family, and not shut us up in this hallway like vermin, nor cry out in disgust at our monstrous visage.”

“It is terrible, how much we are bugs now,” Gregor’s father said. “Please, Gregor, my son, if you have ever cared for your father, you will open the door and care for us, just as if we had never transformed, and were still your same loving relatives.”

“But I cannot open the door,” Gregor said. “I have no hands with which to operate the lock—”

“Please, Gregor,” his mother begged. “You who are a bug only in body must surely understand the greater terror and alienation of second-hand co-buggification. My empathy is so attuned as to cause me incredible pain and distress, to the near-derangement of my senses; I am so very empathetic that when something happens to you, you are murdering me.”

“We are such bugs,” Greta said, kicking out with her legs against the door, such that the plaster fell from the ceiling of Gregor’s bedroom. “We are such bugs, Gregor! If only you could understand us — if only you were possessed with a finely-tuned instrument of sensitivity, as we are, and could imagine our pain and terror, I am sure you would be only too eager to help your poor family, who are the most bugs it is possible to be —”

“Yes, Gregor,” his mother said, tearing through the door with the poker from the fireplace, her hair slipping out of its usual careful arrangement with the effort, “you must not lock us in — you must realize we cannot simply turn our feelings on and off, as you do — that our trilobitation is more than merely literal, as in our case, but goes straight down to the root of our souls — as an empath I dread conflict, but this is a case of survival for me —”

“You are feeling only your own pain, Gregor,” his father said, stepping through the door and carefully removing his shoes before helping his wife and Grete pick their way over the splintered wood and into the room, “but we are feeling ours, and yours, and each other’s, and so much more.”

“Empaths often have a hard time setting boundaries,” Grete said, stationing herself at Gregor’s dorsal segments. “We are soft, and permeable, and very much bugs now, and all of us are late for work, Gregor.”

“If only he could understand us,” said her father, moving closer to Gregor’s compound pigment-pit ocelli, “as we understand him.”

“I understand Gregor so much,” his mother said, sobbing, and wrapping her fingers around one of his fore-legs. Her hands were so soft; everything in the room was as tender as fresh corpseflesh, except for Gregor. “He has no softness to him. As an empath, I cannot see someone in pain without wanting to help.”

“I can’t walk past someone in need without doing something,” Grete said, weeping too. “I don’t care if I lose my job as a traveling salesman, or stay in this hideous, chattering body for the rest of my life, with no one to bring me delicious garbage to eat, or to stow me safely under the sofa.”

“I’m a bug, Gregor,” his father cried. “Gregor, your father is a bug all over! Can’t you feel it? Why can’t you feel what we’re feeling? This morning we awoke from uneasy dreams to find ourselves feeling you transformed in your bed into a gigantic insect. Won’t you help us?” And they all three began to stroke at him, in soft fleshy unison, until the whole room was filled with sympathy.

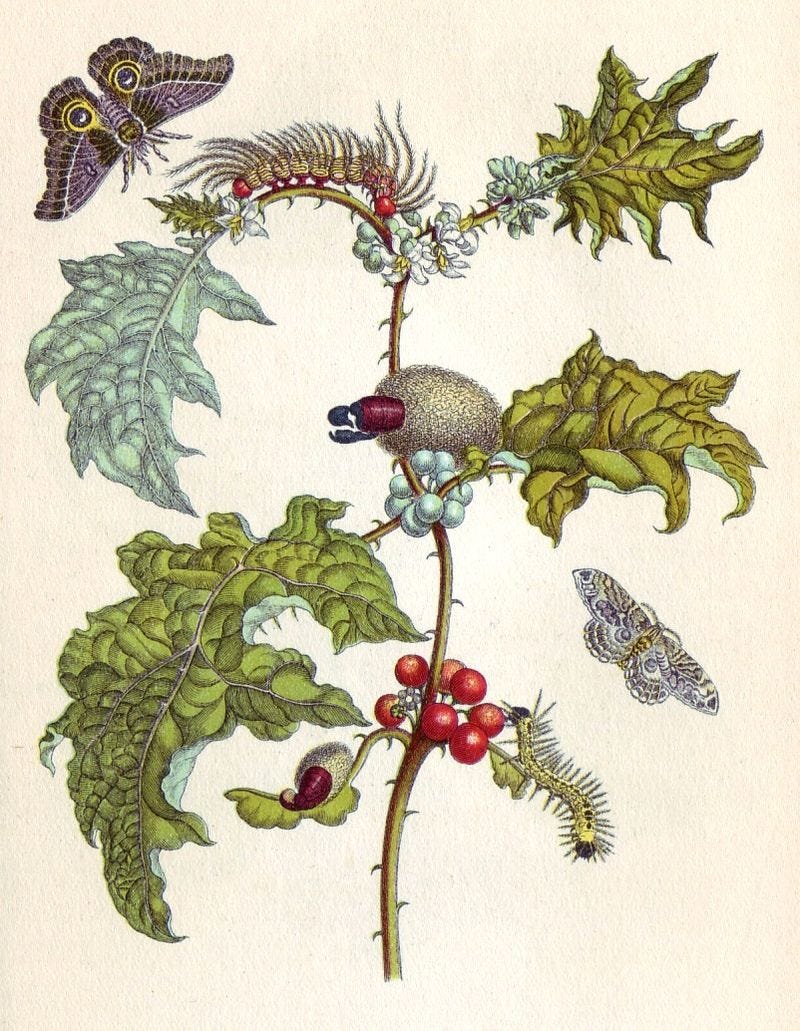

[Image via]

This piece of horror hits home pretty hard and I will be pointing people to it who don't understand my abusive family dynamics because the emotional stuff was so insidious and invisible to other "loving and caring" people.

Parents who say "Why can't you feel what we're feeling?" are more horrifying than becoming a bug!