Love's Work in "Go, Dog, Go"

Do you like my hat?

“Do you like my hat?” -P.D. Eastman, Go, Dog, Go

“There is no democracy in any love relation: only mercy.” -Gillian Rose, Love’s Work

The only narrative to speak of in P.D. Eastman’s Go, Dog, Go follows the repeat encounters between a pink poodle and a yellow dog who might be part beagle. The rest of the book is in a taxonomical style; here is a green dog over a tree, here is a yellow dog under a tree, here are dogs in cars, here are big dogs going up, here are little dogs going down, that sort of thing.

Each encounter runs along the same lines. They say hello; she asks him if he likes her hat; he offers judgment, and they part ways. He never likes any of her hats until the very last; the Party Hat. After he sees the Party Hat they ride off into the sunset together.

(It may interest you to know that the baby calls this book Dog Go Dog, and that he correctly identifies the sunset on the final page by pointing a fat, deliberate hand towards the sun and croaking, “Sun set,” after which he shake the book at me and say, “Dog Go Dog again.”)

While it is true that Go, Dog, Go was published in 1961, you need not worry that the hat subplot tells the story of a woman changing herself for a man. Everyone is changed; all the dogs go.

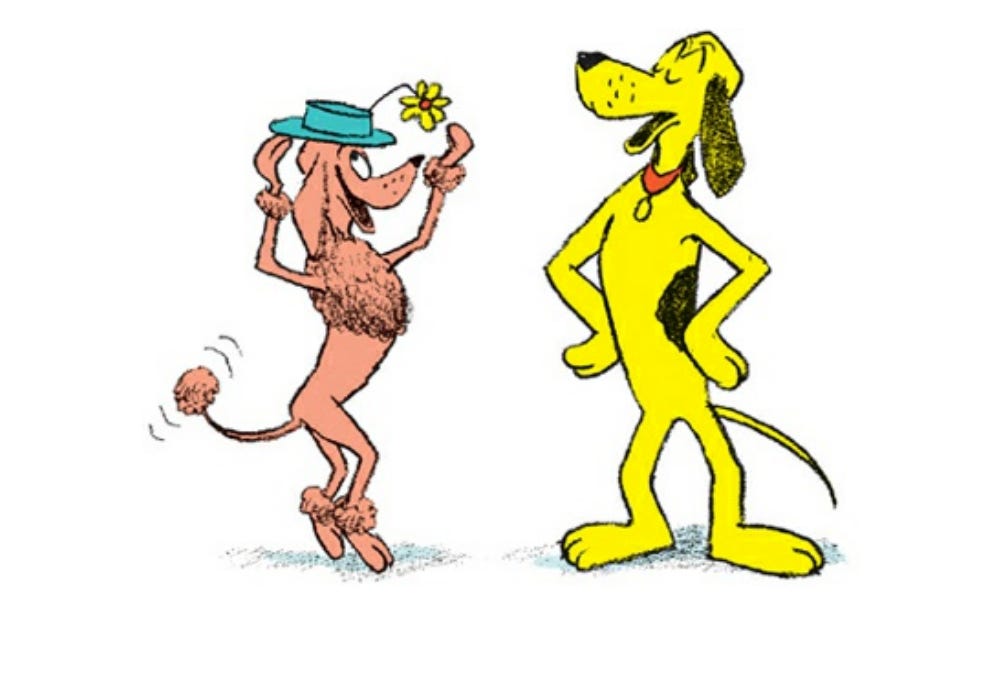

The first encounter

“Hello.”

“Hello.”

“Do you like my hat?”

“I do not.”

“Good-by!”

“Good-by!”

At the moment of parting, we can trust at least that the boy dog has acted without guile. He smiles, and his smile is a friendly one. There is honesty and openness in his gait. Whether he has been rude remains open to debate, but he was asked a fair question and gave a fair reply.

For her part, the pink dog turns to look back at him but does not open her eyes to him in return — she carries out the act of looking until the last possible moment of withholding. She is not pleased, exactly, but neither does she appear truly angry. Both are courteous as they slide out of one another’s lives.

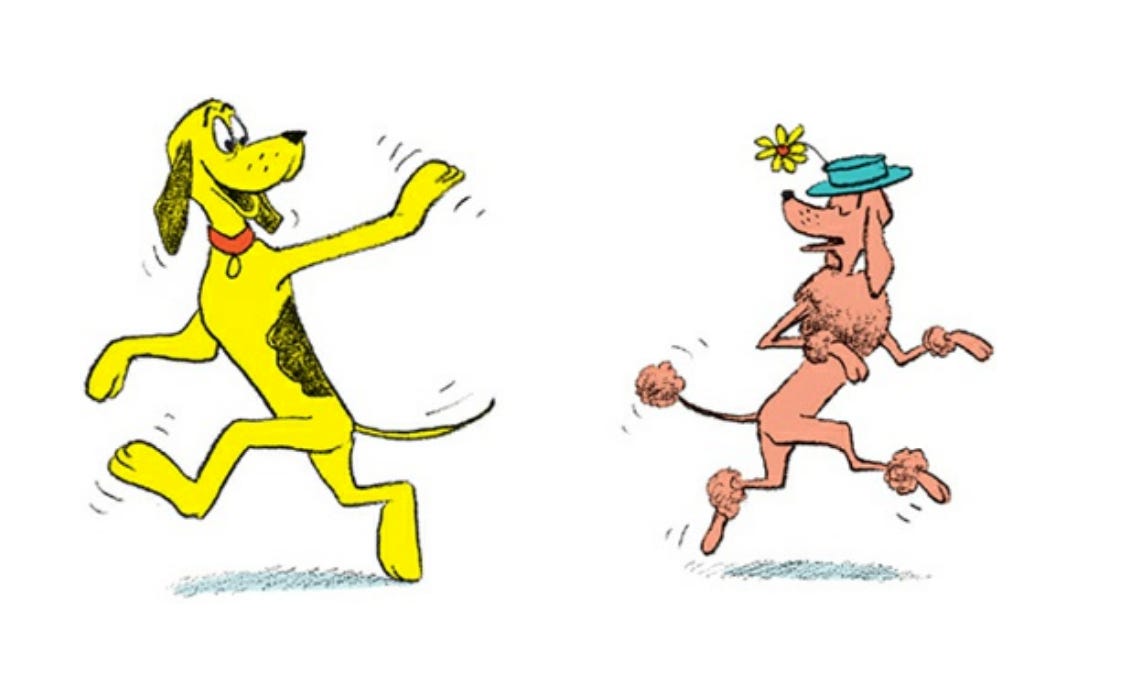

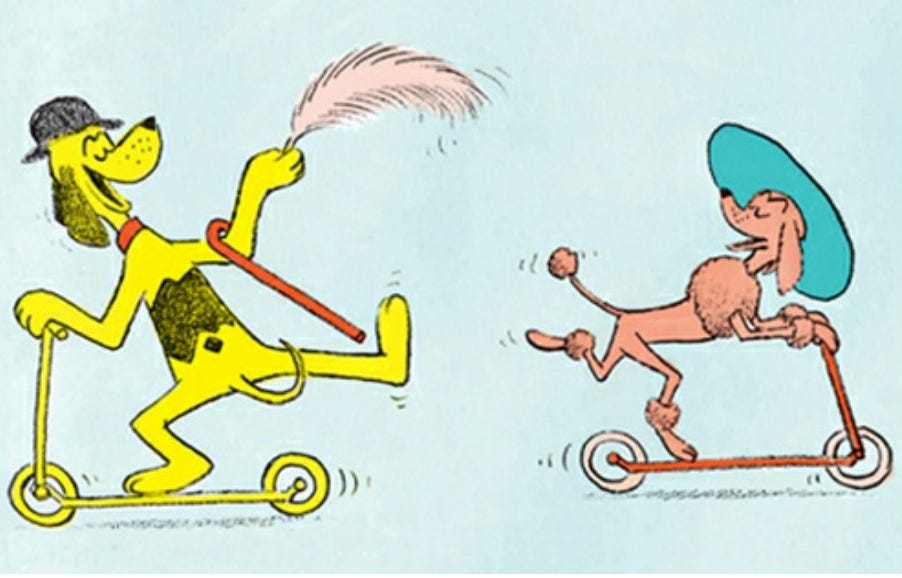

The second encounter

Takes place about thirty pages later. “Hello again,” she says, and you must admit she looks pleased to see him. Not only that, her new hat is larger and more ostentatious than the first! The simple daisy has been replaced by an ostrich feather; the modest sadie has given way to a Gainsborough hat. The size of their smiles! There is joy in the scooting forward on both sides, is there not?

“Hello again,” she says; “Hello,” he says in return, and crucially he takes his hat off to her in greeting. I ask you, who has been changed by their first meeting? She has only become more of herself, while he has adopted a brand-new hat habit.

“Do you like my hat?”

“I do not like it.”

And so good-by again.

Has she given him the feather? Has he stolen it, and if so was it out of pique or cheek? Did he remove it in an effort to “fix” her hat, or to give the lie to his own claim — I don’t like your hat, but I must have some of it to remember you by? Is it simple pigtail-pulling, or was it a cruel gift? Here, if you hate it so much, take it with you — I am all at sea. You can fairly call her expression “miffed” here, I think. She is less pleased with him than himself is.

To return to Rose [emphasis mine]:

“In personal life, people have absolute power over each other, whereas in professional life, beyond the terms of the contract, people have authority, the power to make one another comply in ways which may be perceived as legitimate or illegitimate. In personal life, regardless of any covenant, one party may initiate a unilateral and fundamental change in the terms of relating without renegotiating them, and further, refusing even to acknowledge the change. Imagine how a beloved child or dog would respond, if the Lover turned away. There is no democracy in any love relation: only mercy. To be at someone’s mercy is dialectical damage: they may be merciful and they may be merciless. Yet each party, woman, man, the child in each, and their child, is absolute power as well as absolute vulnerability.”

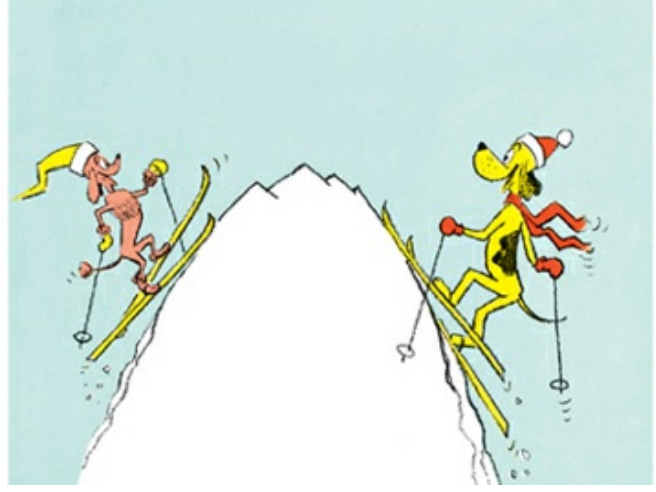

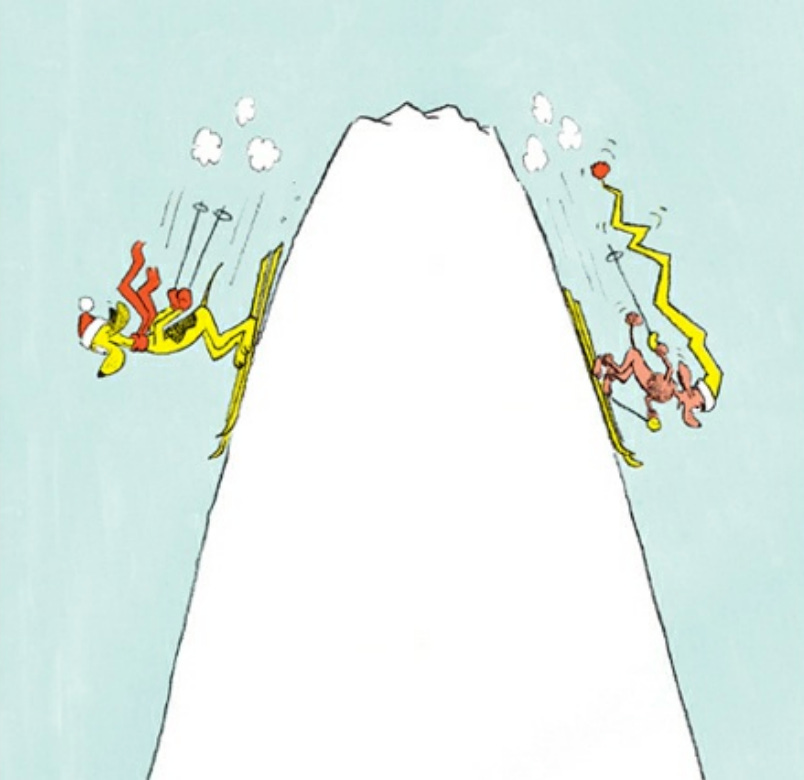

Third encounter

Hello again, this time on a mountaintop. (The third meeting of Love is always charmed.) Hats and smiles worn by each. Equal footing, although she is slightly higher on the mountain than he is. Both dressed for the occasion and prepared to move forward. We must note that after the very first meeting the yellow dog is never again bare-headed. He may not like her individual hats, but we cannot say the same about hats more generally. He becomes an immediate and enthusiastic adopter of hatfulness as soon as the idea is introduced to him.

Once again the pink dog has escalated the scale and intensity of her hats. She seeks his opinion again and again, yet he does not have the final word with her. She would know what he thinks, but he does not guide her path. Her hats have grown bigger than both of them.

“Do you like my hat?” she asks again. She has not been sitting around in front of the mirror, putting her own life on hold until she gains his approval, this pink dog. She has gone skiing around the world. She has acquired and given away ostrich feathers. She has Lived.

This time, I think we can fairly say he appears self-conscious when answering: “I do not like that hat.” There is at last a gap between his honesty and his affection, and he does not like having to speak truthfully to her. Their skis are crossed over one another; they cannot move forward without knocking one another down.

A miracle: By the next panel, without explanation, they have moved past each other with real skill. He smiles and looks forward; she for once casts her eyes back, but only once he can no longer see her. The pink dog only looks back at him when it is impossible for the yellow dog to look back at her!

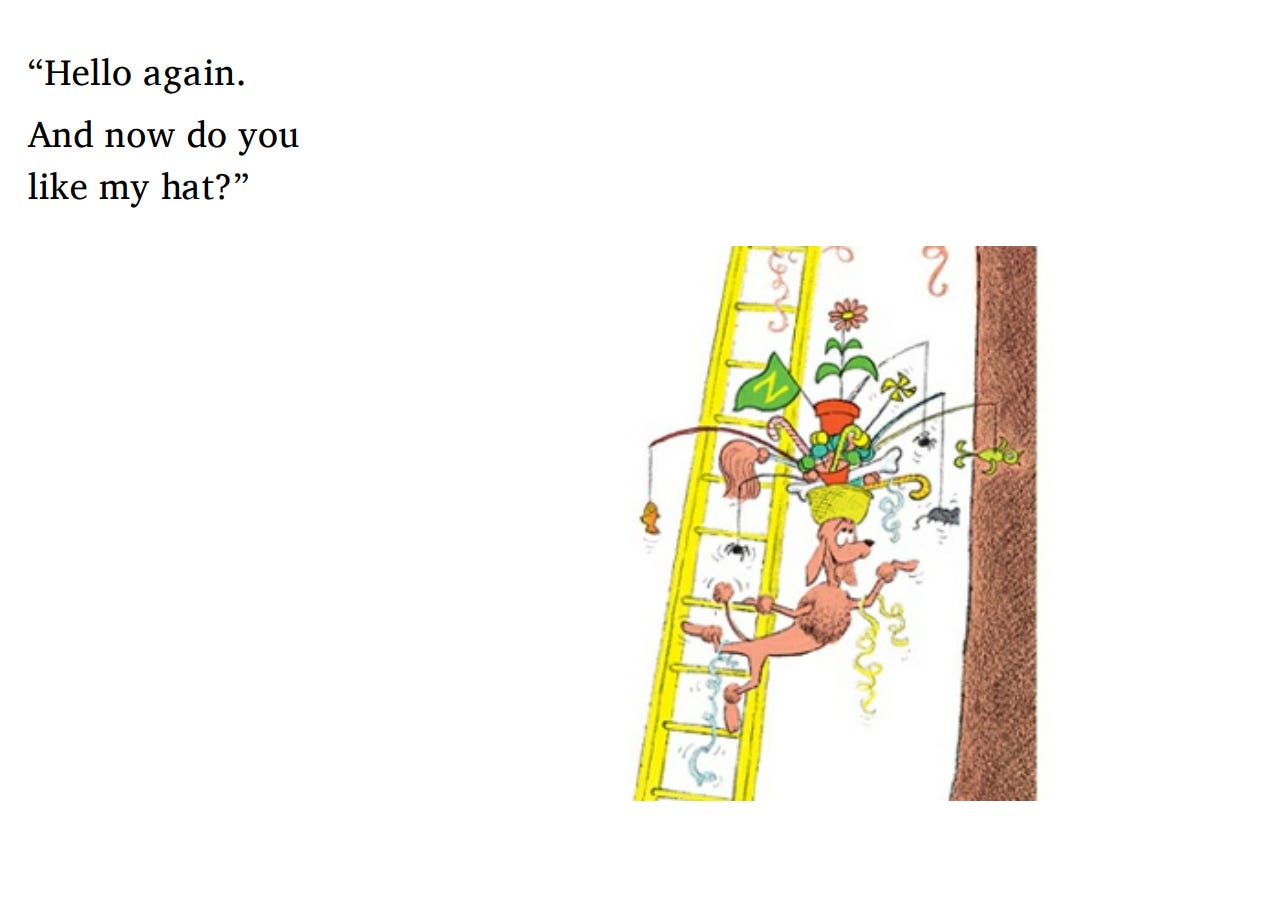

Fourth encounter

At last: The dog party! The big dog party. The pink dog seems to have a sense of an ending, since she asks the yellow dog “And now do you like my hat?” She leans down from the ladder leading up to the dogs’ party tree, like Beatrice in Purgatorio (“I saw the lady whose appearance shook/Me first amid the angelic festival/Gazing upon me now across the brook;/Although the veil beneath the coronal/Twined of minerva’s leaves, from head descending/O’er face and form, did not reveal her all,/Regal of aspect and withal unbending,/Thus she resumed, as who, to hold the ear,/Keeps the most telling words back for the ending:/‘Look on us well; we are indeed, we are/Beatrice”).

Surely the yellow dog who disliked her simple straw boater with a daisy in it, who pulled apart her Gainsborough hat, will recoil at this explosion on her head —

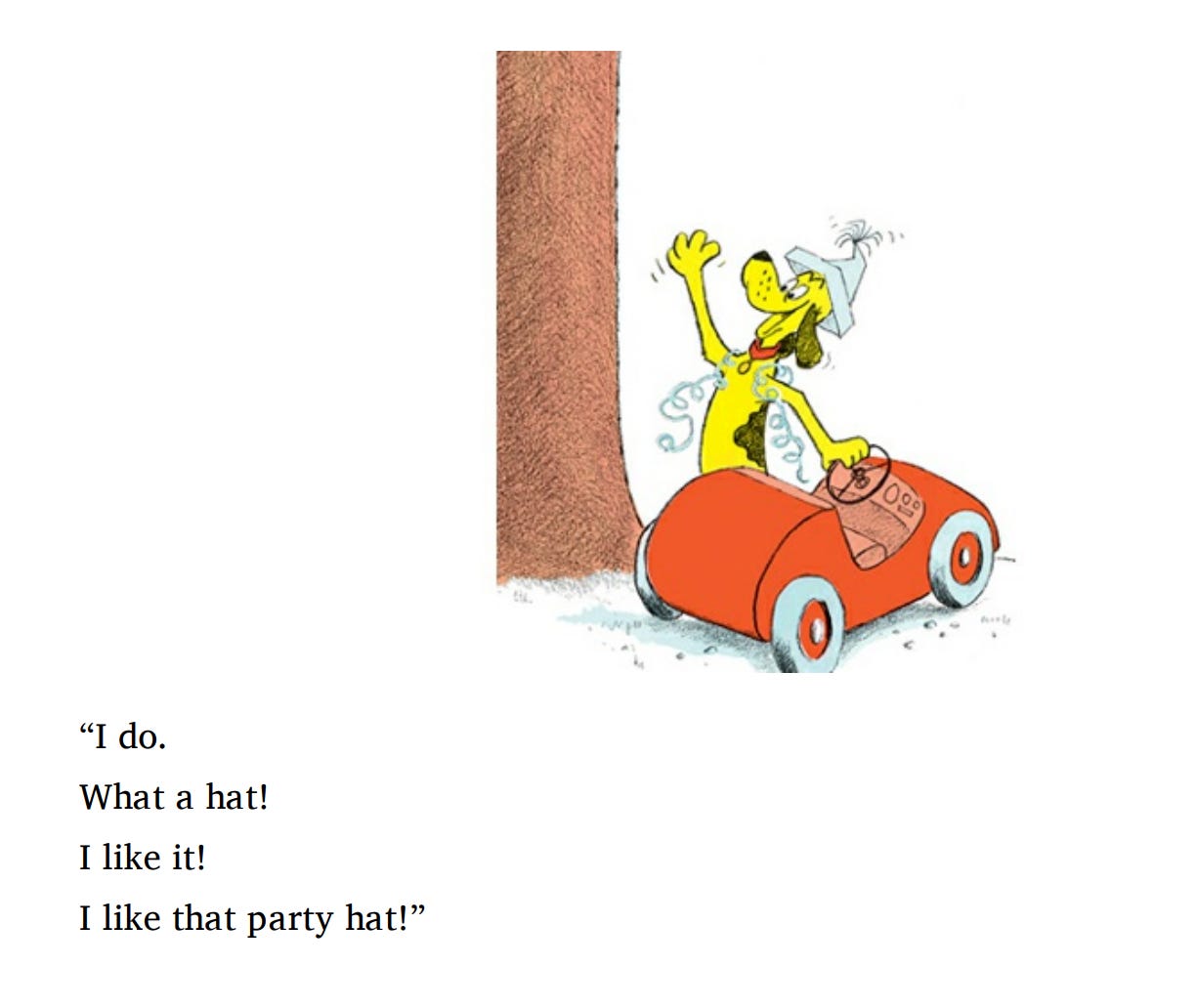

“I do,” he says, and he leaps up as he says it. He says it again, that there may be no doubt in his meaning, “What a hat. I like it — I like that party hat!”

His face is the same, whether he likes the hat or not; he delights in looking at her. Never through a glass darkly; always face to face. They drive off together into the sunset, each in a party hat, with no shadow of parting between them. There is no lesson. There is nothing to learn from their story. It happened, and now you know it, too.

I have read this book 736,297,148,453 times, or possibly 736,297,148,454; I lost count one night.

Sleeping with my then-young granddaughter one night, or rather NOT sleeping, she said to me: “Now it is night. Night is not a time to sleep. It is a time to play.”

I have been thinking and thinking about why this book is so weirdly compelling to my kid, what the deal is with the plot, why to me it feels like a fever dream (and makes more sense when I’m a little bit stoned) written by an off-brand Dr. Seuss—and once more Danny has articulated it all better than I ever could. Bravo.