Northanger Abbey, Part II

Previously: Northanger Abbey, Part I. And people don’t go to Bath in the summer anymore. Have you noticed? Now they all want to go to the seaside and writhe around in a little striped tent that gets towed into the North Sea by a team of donkeys. They call it sea bathing, and it sounds terrible. When I was young going on vacation meant walking back and forth across the Pump Room exactly fifteen times so everybody could watch how you drank sparkling water, and that was excitement enough for us, let me tell you.

Chapter Eleven

It rains. It didn’t seem like it was going to rain, but it did rain. First there were clouds, and then there was rain afterwards, and everyone agreed rain meant wetness. It was a wet day, due in no small part to all the rain, although Mrs. Allen agreed that if the rain would only stop, it would be a very nice day, and a dry one. Then it rained harder, until eventually it stopped. If it doesn’t seem very interesting to read all this, imagine how much less interesting it is for this to happen to you. Most of life isn’t very interesting, you know. That’s why people read Gothic novels.

Miss Tilney was meant to visit Catherine that morning, but rain means mud, and it’s very difficult to walk in the mud without getting dirty, which made Miss Tilney very late, and in the meantime Catherine was lightly kidnapped by the Thorpes. The kidnapping was over pretty quickly, just like the rain, because it turned out the roads were much too muddy to make it to Clifton before sunset, so everybody went home, which is where they ought to have stayed in the first place.

Chapter Twelve

You know when you’re not sure if a friend is mad at you or not, and after a few hours of anxiety, find yourself getting preemptively mad at them for not putting you at ease, as a form of emotional protection, so that they next time you run into one another in public you keep looking over to see if they’re ignoring you or if it’s you who’s ignoring them? It was just like that the next day between Catherine and the Tilneys, since Catherine could not decide if they had slighted her, by visiting her so late in the day that she’d already gone out, or if it was she who had slighted them, by going out herself. It wasn’t any fun.

On the credit side of things, General Tilney agreed with John Thorpe that Catherine was good-looking after all. That brings us up to five good-looking characters, unless I’ve miscounted, and it’s still only four.

Chapter Thirteen

You remember the days of the week. All but one of them had passed by now. Have you ever noticed that if you make one friend on vacation — the kind where you’ve told one another everything there is to know about you by the second night you spend together, and you meet for lunch every day and it’s generally assumed you’re going to do everything together — and then you try to make a second friend, it starts to drive a wedge between yourself and the first vacation friend, even though at home you can easily have multiple friends at the same time? I don’t know why it should be so, but it almost always is.

Catherine tries to reschedule her walk with Miss Tilney, but her brother and the Thorpes band together to prevent it. They’d rather see her dead than on a walk with Miss Tilney. Catherine bands together with herself to reestablish the walk. By God, no one’s going to stop her from taking a walk.

Chapter Fourteen

Catherine takes her walk with the Tilneys at last. “This is just like the south of France,” Catherine says as the pass Beechen Cliff, “I would imagine, never having seen it myself.”

The Tilneys and Catherine all agree that novels are terrific and that everybody ought to buy more. And if I might add my own two cents at this point, they ought to be published on time, so audiences can get the full context, and not have to wait thirteen years for a timely satire on contemporary reading habits. Because reading habits can change a lot in thirteen years, and that isn’t the author’s fault.

Catherine didn’t know anything about drawing, which is a wonderful quality in a good-looking woman. That sounds sarcastic, but it mostly isn’t. There’s a tremendous sort of vacant pleasure that comes from an earnest, handsome boy taking you by the hand and explaining something urgently to you on a hillside, and I wouldn’t take that away from the next generation of girls for all the world. Much more fun than learning about drawing from a drawing-master. If you’ve got to learn about things from someplace, isn’t it better to learn about them from someone young and vibrant, with a great head of hair, who thinks you’re fascinating, than from some dried-up old teacher, who doesn’t even own a horse?

Chapter Fifteen

A point for Isabella, who scores one over on Catherine’s having skipped the second trip to Clifton by announcing she got engaged to Catherine’s brother James on the drive back. She follows this up with an unforced error by promising that she’s going to love Catherine better than her own sisters; Catherine, having five or six sisters at least, does not reciprocate.

Isabella offers what seems to be the fifth or sixth hint that the Thorpes believe the Morlands are millionaires. Catherine lets it sail beautifully over her simple little head. Isabella declares she would gladly live in an old dead dog with James, because money means nothing to her.

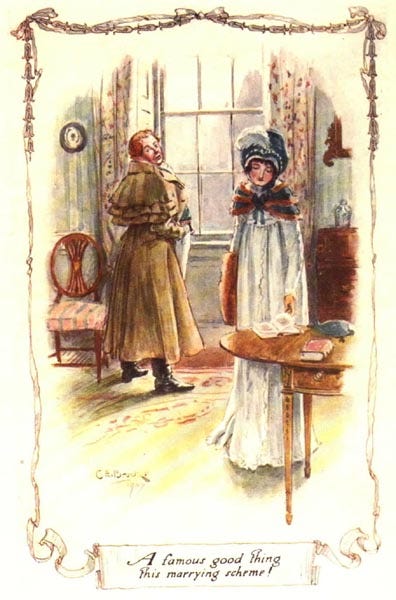

John Thorpe stops by to fidget by the window, and to ask Catherine if she thinks getting married is generally a good idea. “Yes,” she says, a little puzzled, and then he fishes for a few more compliments before at last toddling off.

Chapter Sixteen

Isabella will not dance. She hates dancing! She wants to sit in the corner and think about being engaged and living on coffee grounds and shoestrings in the wonderful little dead dog house of poverty she plans to live in with her faithful fiancé. Then she dances with Henry Tilney’s older brother, who has been introduced by way of contrast.

The Morlands will settle a four hundred pound-living on James, plus an estate of the same value, which apparently adds up to being able to get married in two or three years.

“That’s so great,” says Isabella.

“I agree,” says her mother. “It’s so great. Especially since you didn’t want very much money from them. It really lines up with your expectations, that they’re not giving you very much money to get married with.”

“It sounds like a lot of money to me,” Catherine says, simple as a baby cow.

“Oh yes,” Isabella agrees, lying facedown on the floor. “I only wish it were less. Maybe we can give some of it away, or throw it in a river.”

Chapter Seventeen

General Tilney invites Catherine to come stay with them at Northanger Abbey, and lists all the celebrities he knows for some reason. The Marquis of Longtown. General Courteney.

“I’m afraid I don’t know any of those people,” Catherine says.

“Hah-hah! A very good joke. Of course I understand that my home is an old apple core to you. But please. If you would come stay with us, I would feed you breakfast every morning like a mother bird feeds her chicks.”

“Why won’t anyone believe that I am not a famous millionaire?” Catherine Morland writes in her diary that evening. “But I am glad to be seeing an abbey at last. Thank God for Henry VIII for despoiling them in the first place. Otherwise they might be well-maintained and full of people who lived there in an ordinary sort of way. I wonder what a Catholic is?”

Chapter Eighteen

Catherine and Isabella take their leave of each other. Isabella’s eyes are glued on the doors of the pump-room. “Who are you looking for?” Catherine asks. Even baby cows are not so simple; she is as simple as grass.

“I’m not looking for anyone,” Isabella says, even though her eyes and tongue are hanging out of her mouth like that Awooga wolf from old Tex Avery cartoons. “I’m just relaxing my eyes. You should let them open all the way at least twice a day. It’s good for you. By the way, John has written to tell me he considers the two of you engaged. Don’t try to argue with me about it; he wrote it all down. If you didn’t want to be engaged to him, you should have written it down first. It’s in the Magna Carta.”

“Oh dear,” says Catherine, who has never read it, but will believe anything if you tell her it’s from the Magna Carta. “I really don’t like him at all. But I’m afraid I didn’t think to put it in my diary first.”

“Well, the law is the law,” and then they sat in silence for a while. Then Captain Tilney entered the room, and Isabella shoved Catherine out the window, to make room for him to sit next to her.

Chapter Nineteen

You’re not going to believe this, but Isabella continues to behave badly.

[Image via]

Goddammit you are making me want to reread Northanger Abbey despite my vow to never read it again

“Everyone agreed rain meant wetness.”