Remittance Man

I have a new short story out this month, “Remittance Man,” in a strange fiction anthology called Mooncalves, courtesy of NO Press, which is run by my old pal John Thompson. It also features stories by Sasha Geffen, Brian Evenson, Ernest Ògúnyẹmí, and Chelsea Sutton. You can order Mooncalves here, and I’m including an excerpt from “Remittance Man” for your deliberation, in case you’re on the fence. It’s lightly spooky fun!

I DECIDE TO TRAVEL

Not long ago I encountered the prospect of having more time than employment before me, having recently received from my employer an indeterminate leave of absence after several of the other fellows started having fits. Finding myself so unexpectedly at leisure, and not wanting for various unrelated reasons to stay at home, I made the decision to spend at least the first portion of this idle period in travel. I had certain interests on the road, moreover, whose addressing I thought might bring some profit to my employer, if it were skillfully done. I should add that, in considering these interests, I had not, of course, withheld essential information from my employer, nor acted covertly in order to avoid engaging with the proper channels. My essential nature is organized against the clandestine. These interests did not at the time qualify for my employer’s notice, and there was by no means any reason to expect a change in circumstances that might alter the fact. These were possibilities only in the most generous sense of the word. I say all this by way of explaining that these interests were not the primary or even sustaining principle behind my decision to travel at that time. They merely reinforced a course already established. I could not work, I would not stay to home, so there was nothing else to consider but the road. Travel would clear things.

Less interested in where I might go, then, since any number of locations both far off and close to hand might have served my purposes equally well, I turned my attention to which person or persons I might choose to see. I see no reason to boast about such things, but neither can I affect pointless self-deprecation merely from the fear of being thought to be boasting. I am a skillful man and valuable to my employer. I can travel under my own power, undetected and unimpeded, to many places and on a moment’s notice, sure of my welcome anywhere. This has always been my way, even if I might choose not to exercise these qualities for certain periods. Though it had been some time since I had taken so much as an afternoon from my work, I knew I could count on being received warmly anywhere in my network of acquaintance, which was extensive, having been cultivated over the duration of many years, and not solely by me. I have found it profitable and even gratifying to be known in many places. In addition to the no-mean extent of my personal acquaintance, I am also fortunate in belonging to a well-connected and harmonious family of considerable size, with at least one relative in almost every city worth visiting throughout the breadth of the country. We are a congenial bunch and forever calling upon one another, for no sooner does one member complete his tour of every one but another member is born to one of us, calling for a fresh flurry of visits, introductions, appointments, arrangements, exchanging of goods and services, various cataloging and secretarial inevitabilities, etc. Moreover, I am distinguished even among my own harmonious relatives with a happy knack for concord. I have never lost even a single friend to a harsh word or misunderstanding. I have today as many friends (and more) as I did as a boy, and never fallen out with any of them.

Being now committed to a general course of action, and thinking it merely a question of choosing which of my associates to make happy first, I lost no time, but turned that very first unengaged morning to making inquiries among them. Despite the clearest of intentions and the firmest of wills, I found I could make contact with none of them, nor even retrieve corroboration of any previous correspondence between myself and another person. Large as I knew my circle of acquaintance to be, and unquestionable my preparedness to travel, each attempt to contrive a particular friend out of the general haze, was nonetheless plagued by some colossal error of conception, the plane of my recollection as featureless and unpurchasable as glass. I could draw to my attention the abstraction of friendship, and the approximate sense of having been known as a friend myself, but nothing more particular than this – no names, no dates, no special connections, no distinct face or history – answered the call.

The design in detail might be perfection, the fidelity with which I sought to carry it out complete, my attention rigorous and unflagging, and yet each subsequent attempt collapsed regardless. I knew myself not to be friendless, and yet if called upon could not have furnished a single name to answer on my behalf. I knew, for example, that in the city of ________ I had so many relatives, but precisely which relatives and in which neighborhood remained just beyond my comprehension. That I corresponded extensively, even regularly, with many of these friends and relations was beyond questioning, yet now a series of minute but insurmountable administrative blockages stood between myself and the retrieval of these archives.

I swept out the front door to venture into the city, hoping for an answerable face, looking in on each of my most familiar haunts, and ended exactly where and as I had began my walk, at my own front door, certain I had encountered other people throughout the course of the day, but unable to single any of them out from the general rolls of humanity. Otherwise my memory was unaffected. I retained still my own identity, my place of employment, my general history, my usual grasp of mathematics and political affairs and so on. Physically I felt all right. Not great, but all right. But the sense of being somehow interfered with really enraged me. It was then that one of those beneficial little offices I rely on for storing my messages began to issue a certain pattern which historically indicated a recent arrival, and the name of the sender was that of an old friend and one long known to me. With real relief but no particular expectations I began to read –

I wonder that you do not come to see me. Things are not going at all well in your present situation, but I tell you, it is possible to work out your own regeneration amidst snares. I recommend the strenuous life for men like ourselves, and recall with fondness our days of enlistment together. I suppose you do too? You might well come out and see for yourself how I live at _____. Drop down any time. There is no need to send word of your arrival, since I have been expecting you,

Servius Johnson

I liked his letter but little, and I liked the letter-writer less. It was sneering, it was over-familiar, it lapsed more than once into factual error, it spoke not at all to my tastes, my habits, nor my inclinations, it did not even refer to our shared past beyond acknowledging its existence. The aversion his letter provoked in me, however, made me rather more inclined to see him than otherwise. After all it had been a long time since I had seen my friend, and my curiosity was naturally aroused by such a profound change in his style of correspondence. I might even discover its cause during my visit, if I were sufficiently discreet in my methods. Moreover, I told myself, although our intimacy had lapsed somewhat over the years, he retained a serious claim to my affections as a companion of my youth. Perhaps he had written this strange message under great mental strain or even duress, and I could be helpful in either the diagnosis or treatment of whatever impaired him. And should all this prove ineffectual, I consoled myself, I might still stop to look in on some of my interests on the road to _____.

Here a reader might begin to fear that my not having mentioned the curious mental blankness which had so recently afflicted me meant I was becoming insensible to it. Nothing could be further from the truth. But there is a great deal of elegance and economy of movement granted to sufferers of real dread, just as to dreamers. It seemed clear I would never be rid of this affliction by rushing headlong towards it in the hopes of startling or dislodging a blockage in consciousness, and that careful observation and deliberate strategy would instead serve me better. Distress rather than tactics had impelled me out of my front door to stare vainly through every door and window in my city, and I had lost any hope that any particular face or neighborhood would do the work of ‘jogging’ my memory for me. Aside from a slight headache and an inward tendency towards panic that required regular checking, I felt very much the same as I always did. Better to continue acting the same as I always did, then, so as to be all the readier when I returned at last to myself.

Fortunately, my memories of Servius were not at all affected, and I looked over them with no uncertain pleasure. Ours had been a friendship of immediate rather than accumulative intimacy. I had seen him at the birthday party of a mutual friend — a friend I had in fact hoped to get to know better that very evening, and indeed I had arrived at the party with hardly any other motive, but could scarcely find them in the crush — and knew, rather than wished, our connection to be imminent. I felt none of the self-consciousness that sometimes accompanies a first, unsolicited introduction, and neither did he; what I proposed he immediately seconded, and all our subsequent association looked very much like our first meeting.

You doubtless already know that there are certain senses which do not correspond with any particular organ but are nonetheless innate and universal, and indeed without which it would not be possible for life to function, such as one’s sense of balance, of locomotion, of time. I believe there are similarly certain senses of social perception which govern our actions, impulses, even sometimes our desires, and I believe myself to have been guided by one of those senses then, though I could not tell you what system of discernment was operating within me at the time. Our friendship was characterized from the first by its mutuality, its reciprocity, even unanimity. I carried him off from his own set that evening in a triumph. I cannot say now if I ever saw any of them again.

Certainly whenever Servius and I met in future, it was almost invariably at my apartments rather than his, and among my set, too. He was so easily incorporable I do not think it occurred to me to do otherwise, although I had no other friends I saw in so dramatically one-sided a setting. Those other friends, too, I often met out in the world, at varying times of day, various locations, sometimes alone, sometimes with others, etc., but with Servius our meetings never varied after the first. His was a remarkably easy temperament, and he was always pleased wherever he saw an opportunity to be pleased. I found his companionship infinitely pleasurable whenever I was with him, and had no wish to vary the circumstances, and I assumed he felt the same way.

Whenever he was with me, he occupied the better part of all my thoughts; if I wished to please anyone, it was him, if I wished to entertain anyone or single them out for special favor, he was the most natural candidate, if I wished to show off, or flirt, or triumph in something, he the most natural end. Once, perhaps twice, the thought that I had no idea of how he occupied the hours that were not spent with me gave me pause, but this thought found no purchase within me. How could it? I had no reason to suspect anyone disliked him, that any conduct of his might ever reflect on me in any way, that any trouble might ever arise from such a connection. He was either in my company (and, I felt at the time, very much in my power) or he hardly seemed to be at all. In this way several very agreeable years passed. After first his work, and then mine, took us out of one another’s daily orbits, I experienced the same pleasurable indolence at the circumstances that kept us apart as I had at the earlier circumstances which had pushed us together, and cheerfully lapsed into first occasional, and then only exceptional, correspondence. I had only ever felt secure of him.

I opened to a familiar page of The Book of the Significant Man, the guide I carry with me always, and read the following:

“So long as you don’t make light of my instructions, you will never find yourself caught saying, ‘Come right in, Mr. Agostino,’ to someone whose name is actually Agnolo or Bernardo; and you will not be forced to say, ‘Remind me, what was your name again,’ or say over and over again, ‘I’m not putting it very well,’ nor ‘Gosh, how can I say it,’ nor stammer nor stutter at length in order to remember some word: ‘Mr. Arrigo, no, Mr. Arabico. What am I saying? Mr. Agapito!’”

“You might well come out and see for yourself how I live” was the first invitation Servius had ever issued me. It is possible I had felt flattered then, as well as repulsed. At any rate, it was the only invitation I had to my name, and since I had at least as many excellent reasons for not staying home as I did for going to him, I resolved to lose no further time, and set off for _____ at once.

If you find yourself clamoring for more of “Remittance Man,” as well as other stories like it, you have simply to step over here to be united with the object of your desire.

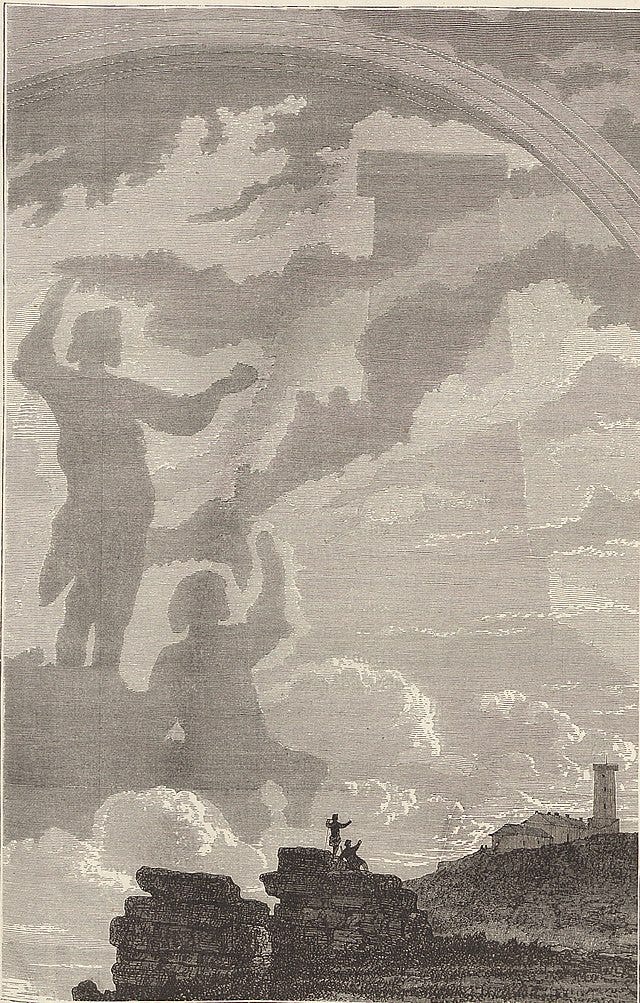

[Image via]

Danny!!!! Marvelous!!!