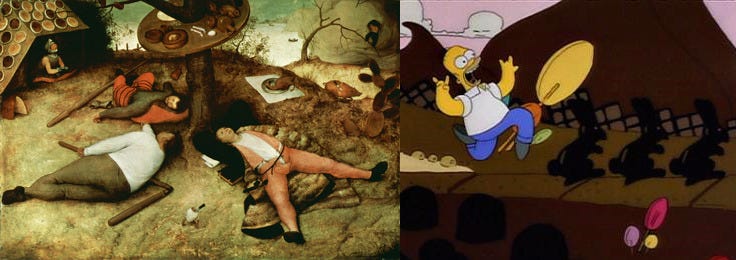

The Battle Between Carnival and Lent: Homer Simpson, The Land of Cockaigne, and The Triumph of The Flesh

“The flight of the ragged and starving masses of the modern era into artificial paradises, worlds turned upside down and impossible dreams of compensation originates from the unbearability of the real world, the low level of sustenance, dietary deficiency and (for contrast) excesses; these inspired an unbalanced, incoherent and spasmodic interpretation of reality.

At the lower level of ‘civil’ society — in the subordinate world of instrumental and ‘mechanical’ beings, tyrannized by their daily use of ‘vulgar breads’, in which the mixture of inferior grains, often contaminated and spoiled by poor storage, or, as happened not infrequently, mixed (sometimes deliberately) with toxic and narcotic vegetables and cereals — the troubled rhythm of an existence verging on the bestial contributed to the formation of deviant models and delirious visions. The dichotomy between the ‘bread of princes and great masters’ and the ‘bread for dogs’ is transformed into a dietary metaphor of the two different cultural systems that find their focal point in bread.”

—Bread of Dreams, Piero Camporesi, trans. David Gentilcore

“Everyone living at the end of the Middle Ages had heard of Cockaigne at one time or another. It was a country, tucked away in some remote corner of the globe, where ideal living conditions prevailed: ideal, that is, according to late-medieval notions and perhaps not even those of everyone living at the time. Work was forbidden, for one thing, and food and drink appeared spontaneously in the form of grilled fish, roast geese, and rivers of wine. One only had to open one’s mouth, and all that delicious food practically jumped inside. One could even reside in meat, fish, game, fowl, or pastry, for another feature of Cockaigne was its edible architecture…The stories about Cockaigne even competed with one another for the greatest entertainment value, incorporating contrasts — as absurd as they were grotesque — to combat the fear, sometimes driven to frantic heights, that this already wretched earthly existence would suddenly take a turn for the worse.”

—Dreaming of Cockaigne: Medieval Fantasies of the Perfect Life, Herman Pleij, trans. Diane Webb

“If you see me, weep.”

–Carved “hunger stone” visible from the Elbe during low tide, Czech Republic

“Let me have men about me that are fat,

Sleek-headed men and such as sleep a-nights.

Yond Cassius has a lean and hungry look.

He thinks too much. Such men are dangerous.”

—Julius Caesar, Act I

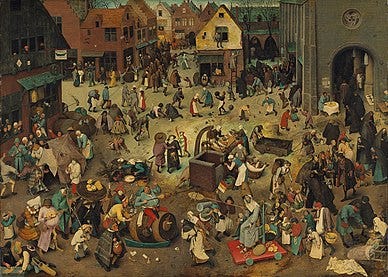

“In Bruegel’s Fight Between Carnival and Lent, everything revolves around food, in arrangements that literature has meanwhile made familiar to us. A fatso standing on a barrel of beer or wine brandishes a meat skewer — full of such edibles as a grilled pig’s head and a roast chicken — at a woman, as wan as she is skinny, whose weapons consist of nothing but a breadboard bearing two lean stockfish and some cracnkel and bread rolls. Other edibles trot alongside the glutton, including an enormous ham with an inviting knife stuck in it, eggs, waffles, white bread, and pancakes. This tub of lard armed to the teeth with food, who portrays the proverbial knight with a full stomach, turns up repeatedly in literature, armed with the lethal meat skewer, carrying hams, suckling pigs, and capons.” (Cockaigne, Pleij.)

Think of Homer Simpson’s greatest enemies: Ned Flanders, Rex Banner, Frank Grimes. Abstemious, frugal, suspicious of pleasure, indifferent to the joys of the table. Rex Banner pushes aside a beautiful ice cream sundae complete with pinwheel candles, insisting “this isn’t a very happy birthday for Rex Banner.” Frank Grimes’ lunch exists only to be stolen. Ned makes nachos “Flanders-stye: That’s cucumbers with cottage cheese,” which is to say, he does not make nachos at all. It is true Lenten food, inventiveness born from desperation and the long shadow of the temperate-agricultural hunger gap, insufficiency named in honor of the memory of plenty.

While it can hardly be argued that The Simpsons has an altogether positive outlook on Homer’s fatness — indeed the show regularly took great and cruel delight in pathologizing fatness, and not merely Homer’s, either — his extravagant, ingenious love of pleasure, ease, and the medieval art of banquetry was so lovingly detailed as to become irresistible, such that the writers might have been said, like Milton, to be “of [Carnival]’s party without knowing it.” Homer’s pleasure is the viewer’s pleasure; we set sail to the land of Chocolate with him, and Slumberland too; his hallucinations are our hallucinations, his comfort our comfort, with appetite unrestrained by limit, shame, or order.

In the Battle Between Carnival and Lent, who takes Lent’s side? Who cheers for dry pretzels and bare trees? Who places Lent in visions of paradise? You don’t win friends with salad.

“Little is known of intentional addiction in the Middle Ages, but times of scarcity frequently made it necessary to switch over to a diet of grasses and seeds. These substitute foodstuffs included hemp and poppies, which filled whole fields in parts of southern Europe. Hallucinations were stimulated in any case by the recurrent lack of certain nutrients. A constant deficiency of essential enzymes also weakened one’s mental state, causing the mind to roam and automatically to dream up more pleasant circumstances. In this way Cockaigne was born again daily in hungry minds seeking hallucinatory compensation for everything the body was so painfully lacking.” (Dreams, Camporesi.)

“As long as an intense fear of hunger persisted, there was a great need for comfort and moral support…Oddly enough, simply not eating was one way of outwitting hunger as well as the fear of it. There were various ways of indulging in rigorous fasting, and — an added attraction — in a state of complete self-denial one was treated to the most wonderful visions….In short, starvation leads to a radical narrowing of consciousness.” (Cockaigne, Pleij.)

The early 16th-century Howleglas (literally “owl-mirror,” apparently a scatalogical pun in early modern Low German that one of you will have to explain to me) follows the adventures of Till Eulenspiegel. In “How Holeglas gat bread for his mother,” he offers his starving relative two practicalities, bread and advice:

As Howleglas’ mother was thus without bread he bethought how he might best get bread for her. He went into a baker’s house, where he asked the baker if he would send his lord for bread, some wheat and some rye, and bade the baker let one go with him and that he should have his money, and the baker was content. And then Howleglas gave the baker a bag that had a hole in the bottom, and therein put he the bread, and so departed with the baker’s lad, and when he was in another street he let fall…

Then knew the baker that he was deceived, and so returned home. Then said Howleglas to his mother: “Eat and make merry when you have it, and fast when you have no more.”

“I’m not a bad guy,” Homer says in season four’s Homer the Heretic. “I work hard and I love my kids. So why should I spend half my Sunday hearing about how I’m going to Hell?” Eat and make merry when you have it. Carnival beats Lent, every time.