The Problem With Blurbs, Or My Problem With Blurbs, Or A Problem With Blurbs I Often Have

Where Problem Is Inclusive But Not Exhaustive

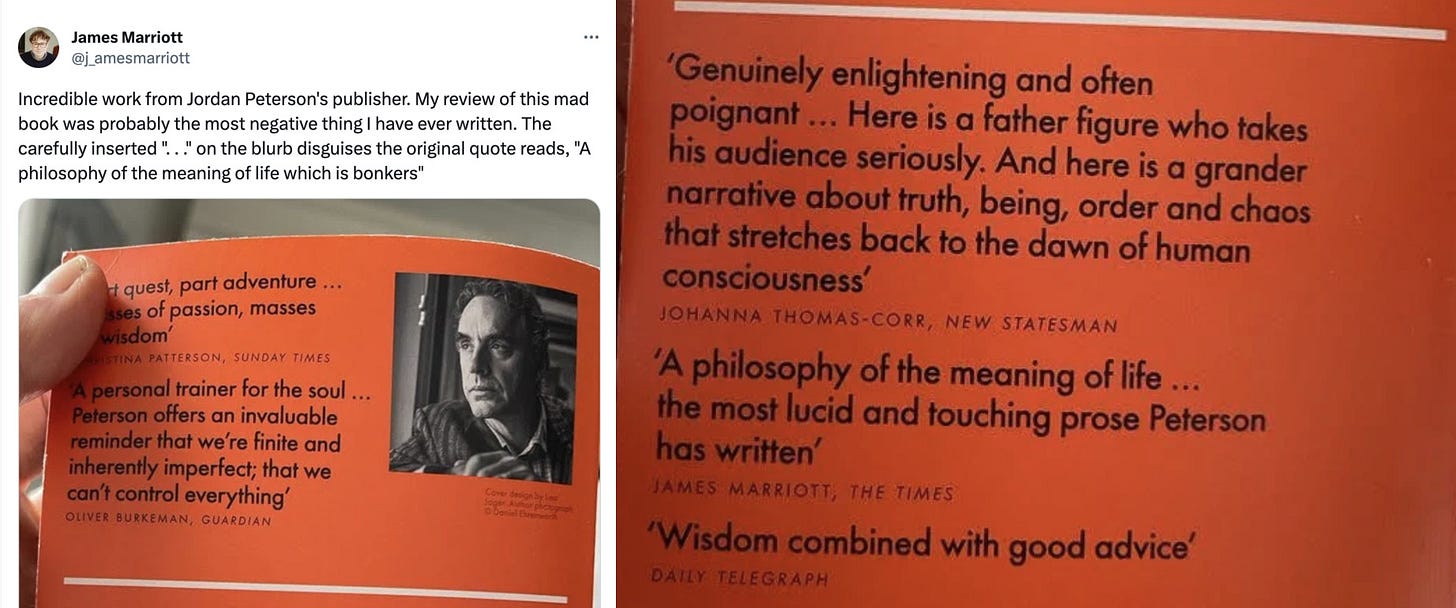

This is not a type of blurb problem I have, but it’s certainly one I always find entertaining, wherein a cheerfully opportunistic publisher chops up a negative review into its smallest possible constituent parts, then reassembles them into the shape of a rave.

I don’t mean to complain about being occasionally asked to write blurbs, I should say. It doesn’t happen very often, and I’m very comfortable saying no if I don’t have the time or don’t think I’ll like the book enough to recommend it; most of the time I say yes and feel pleased and proud to get to do so.

Recently, as a matter of fact, I was called upon to blurb a friend’s new novel. I enjoyed agreeing to do so, I enjoyed reading the book, and I enjoyed thinking about how to describe it to a potential reader.

Then — and this happens every time, as regular as noon — I lose any ability to put a reasonable sentence together. It’s as if I’ve never read a book, never had a conversation, never offered a recommendation to anyone in my life before.

The most deranged phrases occur to me. Suddenly I want to call things “dizzying.” All I can think of are things I’ve read in other blurbs, or lies, or gross misrepresentations of fact. Everything I say sounds wildly inauthentic, and I find myself growing hostile towards my own claims of an interior experience.

I become both Nixon and Homer Simpson in a single moment:

Kennedy [another blurb-writer] says easily and confidently, “I would like to take this opportunity to express my fondness for Duff beer.” I believe them.

Myself-as-Nixon stammers, “Uh, I’d also like to express my fondness for that particular beer.”

Myself-as-Homer objects, shaking with rage, “That man never drank a Duff in his life.”

I know better than to call something a tour-de-force, or unflinching, or worse yet a slim volume of surprising and uncommon power, but aside from being able to mark out the most obvious pitfalls like Scylla and Charybdis, I’m completely lost. Why have I described a book as “readable”? That’s like calling a television show “watchable,” which — hideously — I am almost sure I have done at some point.

Should I call it “generative”? Must I? And why am I suddenly diverted into negative theology? “Book does X — but never at the expense of Y.” “It imagines Z, but without ever getting bogged down by A.”

I can say something like “It made me miss my subway [or bus] stop,” which is doubly effective because it makes me sound like I’ve got the common touch — I ride the bus! I’m not one of those stuck-up guys who has a rolling ladder in his library and imprisons local women — and makes the book sound engrossing. But then I want to say it all the time, and while I hardly think anyone is out there fact-checking blurbs, if you claim 5 or 6 books in a row all made you miss your bus stop, it sounds less like any of the individual books were anything special, and more like you’re forgetful. Or worse, like you’re trying to cultivate a charmingly forgetful, absent-minded persona on purpose.

Most of this anxiety can be chalked up to a power fantasy, I think. I’ve read loads of blurbs, mostly by accident, over the nearly thirty-seven years of my book-reading life, but I’ve never given them very much thought. If any struck me as slightly clumsy or cack-handed, I didn’t hold it against the writer; it’s difficult to write marketing copy, perhaps especially for something you really like, and still sound remotely human. If any appealed to me, I read the book, and naturally the itself book always affected me more than the blurb did.

It’s only when writing a blurb that anyone becomes really interested in blurbs, and is tempted to externalize that interest to everyone else around us. I don’t always think overthinking is a real problem, but it might be when it comes to writing a blurb. They almost always sound a little hokey; this isn’t a reason to lean into hokiness, of course, but it should encourage one to relax a little. The idea isn’t to write a blurb that’s so good it ought to be a book by its own merits; the idea is to communicate more or less generally that you liked the book, or its author, or both, for one or more reasons you think might also apply to somebody else.

If there is a problem to be diagnosed in the blurbing world, it’s probably an internal engine driving us towards compliment inflation. We worry that just saying “It’s a good book, and I liked it” will seem damningly faint praise, so almost no one ever writes a blurb like that. But then again, everything can’t be a luminous revelation, can it? It’s possible words fail me, in blurbing, both because I have to keep it short and because I’m not really just discussing a book I liked with a friend, free to discuss its various points at leisure; I’m pressing my own enjoyment into service to try to help the author move copies. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to sell copies of a book, but it certainly does increase the overall sensation of flop sweat while trying to come up with something snappy, at least for me.

Occasionally one sees joke books with “wacky” blurbs about how the author owes Mel Brooks money or something, and it’s sort of funny, but that offers diminishing returns, too. What I think we need a bit more of are books with conspicuously sober blurbs. Not humorously underhanded digs, I mean, nothing with a joke to be located, just readjusting the average, steering away from boosterism:

“I enjoyed this book.”

“The sixth chapter was the best one, I thought.”

“I’d like to read something else by this author, maybe when I have more time next summer.”

“If you like ____ by ____, odds are good (not “you’ll love” or “you’re sure to love”) you’ll like this.”

You see what I mean? Calm, reasonable claims that reassure the would-be buyer they are not being lied to by a bunch of carnival barkers and maniacs, that serve as a reminder of the very real virtues of the pretty-good. W. Somerset Maugham said he stood “in the very first row of the second-raters” in his memoir The Summing Up, which is a very good get, like calling yourself the second-cheapest wine on the menu, and not for nothing an excellent method of gathering more praise and less criticism than you might have otherwise.

This is particular on my mind lately, I think, because I am right in the middle of the manuscript of my first novel, Women’s Hotel. It’s a book that’s very much concerned with middleness — the middle of the century, edge cases of middle-classness, middling talent, and insufficient ambition.

It’s also reminded me how very difficult it is to write a pretty-good novel. Frankly, it’s more difficult to write garbage than I would like. I don’t usually think of myself as a writer who experiences stuckness often; this is in no small part because I’ve mostly made a living from blogging, and taken my cues from former newspaper-types (Robert Benchley, Don Marquis, Dear Abbey, Marjorie Hillis); writing that one churns, turns out, hands over, punches up, and moves past more quickly than otherwise.

It’s possible that there is no other blurb necessary than “Try it…you’ll like it!,” a slogan I always mistakenly associate with Life cereal (I’m thinking of “Hey, Mikey! He likes it!” of course), but which actually comes from a 1972 Alka-Seltzer spot.

“Came to this little place,” the man says, already in media res, authoritatively wiping his mouth in a way that lets the viewer know he knows how to eat, “Waiter says, ‘Try this, you’ll like it,” with the faintest hint of an ethnic burlesque. “What’s this?” he says as himself, “Try it, you’ll like it,” he groans beatifically as the waiter, then “But what is it?” as himself again.

“Try it, you’ll like it,” he sings, fully Italian now. “So I tried it — Thought I was gonna die,” and his voice drops back into an Anglo-Saxon basement, the butch equivalent of “And then I stepped on the Ping-Pong ball.”

“Took two Alka-Seltzers. Alka-Seltzer works. Try it,” he intones, inhabiting the never-seen waiter one last time, haunting his own impression with an ever-present ironic echo, a ghost of a ghost, “You’ll like it.”

Try it! You’ll like it. More than that I can’t say here; there isn’t any room for it.

Great, now I've missed ANOTHER bus

A new Chatner subscriber writes: "A dizzying post that made me want to : be asked to write a blurb for something myself, rewatch more old Alka Selzter ads, and get a hold of Mr. Lavery's first novel when it come out. "