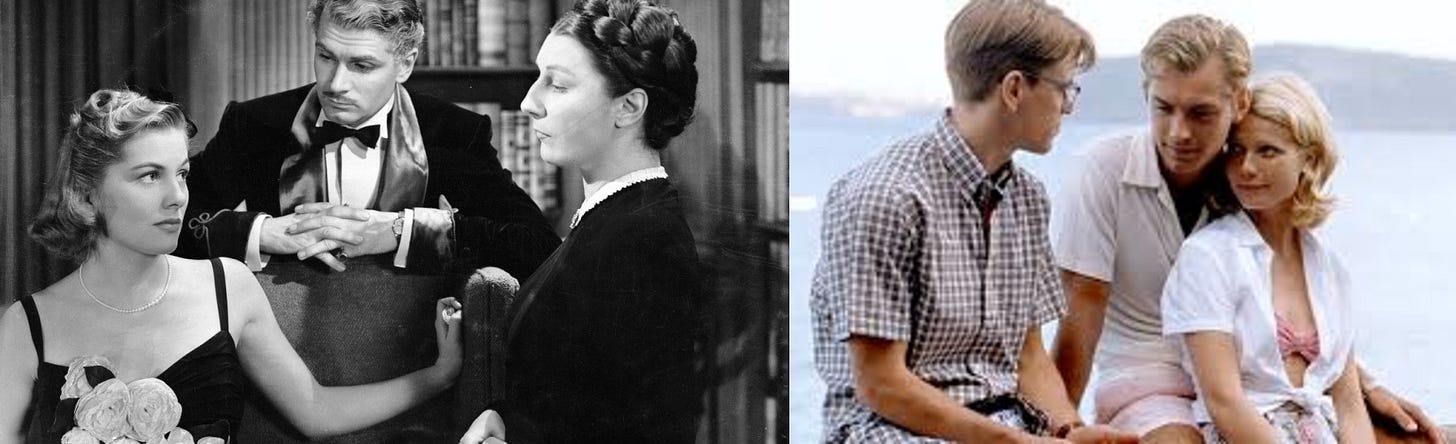

The Talented Mr. Ripley and the Second Mrs. de Winter

Spoilers for both Rebecca and The Talented Mr. Ripley follow.

Recently I had occasion to sketch a brief comparative character study of Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley and Daphne du Maurier’s second Mrs. de Winter, two of literature’s sulkiest schoolboys. Both are fond of slouching, stuffing their hands in their pockets, treating their ersatz-husbands like King Quarterback Bully-My-Love, avoiding women, barely suppressing a murderous rage against rivals for King Bully’s attention, slotting everyone they come across into a rival-or-burly-protector index, and responding to abstract vaginal imagery with terror and revulsion (no reason!!!). One can easily imagine swapping them into one another’s stories and causing nearly-identical havoc. The unnameable second Mrs. de Winter never loves Maxim better than when she learns he’s “accidentally” killed his wife (“My heart was light like a feather floating in the air”), and is only frustrated she was too love-shy to ask him about it sooner (“Maxim would have told me these things four months ago, five months ago”); as happy as Tom persuades himself he is as Dickie’s replacement, by the end of TTMR he can admit to himself that if only he’d played his cards right he “could have lived with Dickie for the rest of his life, travelled and lived and enjoyed living” instead of living in Dickie’s clothes. Both love their man and their man’s personal effects with the same world-obliterating love, trapped on different ends of the “fuck them or be them” conundrum. Both physically small, where that smallness seems to signal queerness in a way they’re both terribly proud of and deeply resentful about, both itchy and disgusted by the proximity of anyone else’s queerness, except for His, and of course it’s not queer when it comes from Him, just (I’m not, are you? You go first. I’ll be right in. Let’s both say it on the count of three. I’m not. She might be. He is. Look, over there — up in the sky — it’s someone else’s queerness) —

Happy, unhappy, dressed up, dressed down, he loves me, he loves me not. The Don’t Call Me By Your Name twins, the past and present Mr. Tom de Winter, née nothing in particular.

Male Accessories

If Mrs. deW2 had her way, she’d do nothing but watch Maxim light cigarettes with an elegant (yet masculine!) manicured hand for the rest of her life; there are over a dozen references to her “scrubby,” “schoolboyish,” hard-bitten nails in Rebecca.

Before she could trap him into a resurrection of their first meeting he had handed her his cigarette case, and the business of lighting-up stalled her for the moment. ‘I don’t think I should care for Palm Beach,’ he said, blowing the match, and glancing at him I thought how unreal he would look against a Florida background. He belonged to a walled city of the fifteenth century, a city of narrow, cobbled streets, and thin spires, where the inhabitants wore pointed shoes and worsted hose.

His face was arresting, sensitive, medieval in some strange inexplicable way, and I was reminded of a portrait seen in a gallery, I had forgotten where, of a certain Gentleman Unknown. Could one but rob him of his English tweeds, and put him in black, with lace at his throat and wrists, he would stare down at us in our new world from a long-distant past—a past where men walked cloaked at night, and stood in the shadow of old doorways, a past of narrow stairways and dim dungeons, a past of whispers in the dark, of shimmering rapier blades, of silent, exquisite courtesy.

THERAPIST: “Would you say you were in love with him?”

TOM RIPLEY: “In love? With Dickie? Perverse. Disgusting. I just want to look at his rings on my fingers while nothing else happens to me for the rest of my life.”

Anticipation! It occurred to him that his anticipation was more pleasant to him than his experiencing. Was it always going to be like that? When he spent evenings alone, handling Dickie’s possessions, simply looking at his rings on his own fingers, or his woollen ties, or his black alligator wallet, was that experiencing or anticipation? Beyond Sicily came Greece. He definitely wanted to see Greece. He wanted to see Greece as Dickie Greenleaf with Dickie's money, Dickie's clothes, Dickie’s way of behaving with strangers.

Venomous Descriptions of Women Who Have Committed The Unforgivable Sin of Enjoying Food

Mrs. deW2 ranks women (both the kinds she approves of and the kinds she doesn’t) according to how persuasive she finds their boyishness; Rebecca is a rapacious, unnatural monster but has the distinct advantage of “looking like a boy in a sailor suit,” Beatrice lands too close to unbecoming mannishness to be worthy of admiration, but is still better than Mrs. Van Hopper, who enjoys eating breakfast, talking on the phone, and not dying at the age of 25 and is therefore fit only for the guillotine.

[Mrs. Van Hopper] would precede me in to lunch, her short body ill-balanced upon tottering, high heels, her fussy, frilly blouse a complement to her large bosom and swinging hips, her new hat pierced with a monster quill aslant upon her head, exposing a wide expanse of forehead bare as a schoolboy’s knee. One hand carried a gigantic bag, the kind that holds passports, engagement diaries, and bridge scores, while the other hand toyed with that inevitable lorgnette, the enemy to other people’s privacy.

Marge Sherwood is Tom Ripley’s Ned Flanders. If she wears a nice pair of pants, it ruins his day; if she enjoys a sandwich, he thinks about drowning her in the Adriatic.

Marge was already dressed in slacks and a sweater, black corduroy slacks, well-cut and made to order, Tom supposed, because they fitted her gourd-like figure as well as pants possibly could…Marge smiled gaily. She was always in a good mood when they were about to eat.

There’s Something About This Georgia O’Keefe Painting That Makes Me Want To Commit Murder; Can’t Quite Put My Finger On It

“Women are untidy. I am a broom.” — Mrs. deW2

No wildflowers came in the house at Manderley. He had special cultivated flowers, grown for the house alone, in the walled garden. A rose was one of the few flowers, he said, that looked better picked than growing. A bowl of roses in a drawing room had a depth of color and scent they had not possessed in the open. There was something rather blowzy about roses in full bloom, something shallow and raucous, like women with untidy hair.

“Wait a minute…there’s something bothering me about this place. I know! This lesbian bar doesn’t have a fire exit! Enjoy your death trap, ladies.”

He showed Marge the front entrance of the house, with its broad stone steps. The tide was low and four steps were bared now, the lower two covered with thick wet moss. The moss was a slippery, long-filament variety, and hung over the edges of the steps like messy dark-green hair. The steps were repellent to Tom, but Marge thought them very romantic. She bent over them, staring at the deep water of the canal. Tom had an impulse to push her in.

My Favorite Food is Nothing

Mrs. deW2’s most frequent response to mealtime throughout Rebecca is to describe in loving detail the food that has been set before her, and how much she doesn’t want it. She might steal a biscuit in private and eat it in shame, but you’ll never catch her lunching. You’ll never catch her at anything — she’ll take her pleasures in private or not at all.

I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now.

“Will you be taking lunch?” said Robert.

“No,” I said, “No, you might bring me some tea, Robert, in the library. Nothing like cakes or scones. Just tea and bread and butter.”

Tom “I’ll have what he’s having” Ripley likes food when handsome men are eating it, is vastly indifferent when father figures are eating it, and riddled with fury and contempt when women do it. Both Tom and Mrs. deW2 protest they don’t want anything, when in fact their hunger is catastrophically, vampirically, immense, only they’d rather starve to death than get a drop less than everything they want.

Tom felt a little hungry, though he rather liked the idea of going to bed hungry tonight…he stopped at a bar-tabac and ordered a ham sandwich on long crusty bread and a glass of hot milk because a man next to him at the counter was drinking hot milk. The milk was almost tasteless, pure and chastening, as Tom imagined a wafer tasted in church.

Crying Over Gifts

There’s nothing quite so embarrassing as a present from a friend, unless it’s letting your husband’s expensive furniture see you unraveling completely because you don’t know how to process positive attention.

A large parcel arrived one morning, almost too large for Robert to carry. I was sitting in the morning room, having just read the menu for the day. I have always had a childish love of parcels. I snipped the string excitedly, and tore off the dark brown paper. It looked like books. I was right. It was books. Four big volumes. A History of Painting. And a sheet of notepaper in the first volume saying “I hope this is the sort of thing you like,” and signed “Love from Beatrice.” I could see her going into the shop in Wigmore Street and buying them. Looking about her in her abrupt, rather masculine way…

There was something rather sincere and pathetic about her going off to a shop in London and buying me these books because she knew I was fond of painting. She imagined me, I expect, sitting down on a wet day and looking solemnly at the illustrations, and perhaps getting a sheet of drawing-paper and a paint-box and copying one of the pictures. Dear Beatrice. I had a sudden, stupid desire to cry.

Tom Ripley’s Guide to Etiquette: The correct response to a fruit basket is to leave the country forever and murder the son of whomever sent it to you (drowning).

He saw a big basket of fruit on the floor by his bed. He seized the little white envelope eagerly. The card inside said:

Bon voyage and bless you, Tom. All our good wishes go with you.

Emily and Herbert Greenleaf

The basket had a tall handle and it was entirely under yellow cellophane — apples and pears and grapes and a couple of candy bars and several little bottles of liqueurs. Tom had never received a bon voyage basket. To him, they had always been something you saw in florists’ windows for fantastic prices and laughed at. Now he found himself with tears in his eyes, and he put his face down in his hands suddenly and began to sob.

A Friendless Future

“They’re all going to laugh at me.”

But even as he spoke I remembered those advertisements seen often in good class magazines where a friendly society demands succor for young women in reduced circumstances; I thought of the type of boardinghouse that answers the advertisement and gives temporary shelter, and then I saw myself, useless sketchbook in hand, without qualifications of any kind, stammering replies to stern employment agents. Perhaps I should have accepted Blaize’s ten percent.

“Do you know, I’m beginning to suspect this contemptuous straight man who pretends not to notice the desires of others and I don’t have the same definition of friendship…”

Tom felt a painful wrench in his breast, and he covered his face with his hands. It was as if Dickie had been suddenly snatched away from him. They were not friends. They didn’t know each other. It struck Tom like a horrible truth, true for all time, true for the people he had known in the past and for those he would know in the future: each had stood and would stand before him, and he would know time and time again that he would never know them, and the worst was that there would always be the illusion, for a time, that he did know them, and that he and they were completely in harmony and alike. For an instant the wordless shock of his realization seemed more than he could bear. He felt in the grip of a fit, as if he would fall to the ground. It was too much: the foreignness around him, the different language, his failure, and the fact that Dickie hated him. He felt surrounded by strangeness, by hostility.

God, I Love Servants

What a hidebound couple we must seem, clinging to custom because we did so in England. Here, on this clean balcony, white and impersonal with centuries of sun, I think of half past four at Manderley, and the table drawn before the library fire. The door flung open, punctual to the minute, and the performance, never varying, of the laying of the tea, the silver tray, the kettle, the snowy cloth. While Jasper, his spaniel ears a-droop, feigns indifference to the arrival of the cakes. That feast was laid before us always, and yet we ate so little.

Those dripping crumpets, I can see them now. Tiny crisp wedges of toast, and piping-hot, floury scones. Sandwiches of unknown nature, mysteriously flavored and quite delectable, and that very special gingerbread. Angel cake, that melted in the mouth, and his rather stodgier companion, bursting with peel and raisins. There was enough food there to keep a starving family for a week. I never knew what happened to it all, and the waste used to worry me sometimes.

The ship was moving before Tom dared to go down to his room again. He went into the room cautiously. Empty. The neat blue bedcover was smooth again. The ashtrays were clean. There was no sign they had ever been here. Tom relaxed and smiled. This was service! The fine old tradition of the Cunard Line, British seamanship and all that!

God, I Hate Servants

She need not have disturbed herself, for the waiter, with the uncanny swiftness of his kind, had long sensed my position as inferior and subservient to hers, and had placed before me a plate of ham and tongue that somebody had sent back to the cold buffet half an hour before as badly carved. Odd, that resentment of servants, and their obvious impatience. I remember staying once with Mrs. Van Hopper in a country house, and the maid never answered my timid bell, or brought up my shoes, and early morning tea, stone cold, was dumped outside my bedroom door. It was the same at the Côte d’Azur, though to a lesser degree, and sometimes the studied indifference turned to familiarity, smirking and offensive, which made buying stamps from the reception clerk an ordeal I would avoid.

Anna was in the kitchen, preparing lunch.

“Anna, there’ll be one more for lunch,” Tom said. “A young lady.”

Anna's face broke into a smile at the prospect of a guest. “A young American lady?”

“Yes. An old friend. When the lunch is ready, you and Ugo can have the rest of the afternoon off. We can serve ourselves.”

“Va bene,” Anna said.

Anna and Ugo came at ten and stayed until two, ordinarily. Tom didn’t want them here when he talked with Marge. They understood a little English, not enough to follow a conversation perfectly, but he knew both of them would have their ears out if he and Marge talked about Dickie, and it irritated him.

What’s The Matter, Don’t You Like It? I Wore It Specially for You

“Funny how dressing up like a woman doesn’t seem to work, somehow.” — Mrs. deW2

My heart fluttered absurdly, and my cheeks were burning. What fun it was, what mad ridiculous childish fun! I smiled at Clarice still crouching on the corridor. I picked up my skirt in my hands. Then the sound of the drum echoed in the great hall, startling me for a moment, who had waited for it, who knew that it would come. I saw them look up surprised and bewildered from the hall below.

“Miss Caroline de Winter,” shouted the drummer.

I came forward to the head of the stairs and stood there, smiling, my hat in my hand, like the girl in the picture. I waited for the clapping and laughter that would follow as I walked slowly down the stairs.

Nobody clapped, nobody moved. They all stared at me like dumb things. Beatrice uttered a little cry and put her hand to her mouth. I went on smiling, I put one hand on the banister.

“How do you do, Mr. de Winter,” I said.

Maxim had not moved. He stared up at me, his glass in his hand. There was no color in his face. It was ashen white. I saw Frank go to him as though he would speak, but Maxim shook him off. I hesitated, one foot already on the stairs. Something was wrong, they had not understood. Why was Maxim looking like that? Why did they all stand like dummies, like people in a trance?

Then Maxim moved forward to the stairs, his eyes never leaving my face. “What the hell do you think you are doing?” he asked. His eyes blazed in anger. His face was still ashen white.

“Funny how dressing up like a man doesn’t seem to work, somehow.” — Tom Ripley

He chose a dark-blue silk tie and knotted it carefully. The suit fitted him. He re-parted his hair and put the part a little more to one side, the way Dickie wore his. “Marge, you must understand that I don’t love you,” Tom said into the mirror in Dickie’s voice, with Dickie’s higher pitch on the emphasized words, with the little growl in his throat at the end of the phrase that could be pleasant or unpleasant, intimate or cool, according to Dickie's mood…

Tom darted back to the closet again and took a hat from the top shelf. It was a little grey Tyrolian hat with a green-and-white feather in the brim. He put it on rakishly. It surprised him how much he looked like Dickie with the top part of his head covered. Really it was only his darker hair that was very different from Dickie. Otherwise, his nose — or at least its general form — his narrow jaw, his eyebrows if he held them right —

“What’re you doing?”

Tom whirled around. Dickie was in the doorway. Tom realized that he must have been right below at the gate when he had looked out. “Oh — just amusing myself,” Tom said in the deep voice he always used when he was embarrassed. “Sorry, Dickie.” Dickie’s mouth opened a little, then closed, as if anger churned his words too much for them to be uttered. To Tom, it was just as bad as if he had spoken.

Dickie advanced to the room. “Dickie, I’m sorry if it —”

The violent slam of the door cut him off. Dickie began opening his shirt scowling, just as he would have if Tom had not been there, because this was his room, and what was Tom doing in it? Tom stood petrified with fear. “I wish you’d get out of my clothes,” Dickie said.

Tom started undressing, his fingers clumsy with his mortification, his shock, because up until now Dickie had always said wear this and wear that that belonged to him. Dickie would never say it again.

i would like to register my interest in literary criticism pertaining to internecine sexual resentment going forward

absolutely, without a doubt, yes

narrator/G--------/Tedward is also Richard from The Secret History re: social climbing anxiety-shame & wanting to be adopted by someone who will tell him where his place is & put him there & lend him sweaters! or I think so. but I'm not sure that Richard is also Tom, Richard would never do a murder if it wasn't a social obligation, I don't think he is good at it or considers it quite his own special subject.

this is a very delicate & tricky equation