Apple-Shot: On A Christmas Story, Body Blocking, Childhood and the Avoidance of Violence

“There is no such thing as "taking aim" with an arrow. He is a bungling archer who attempts it. Shoot from the first by your sense of direction and elevation. It will surprise you at first to see how far you will miss, but soon you will begin to close in with your arrows towards the gold.”

- Maurice Thompson, The Witchery of Archery, 1878

I share my friend Jane Marie’s ambivalence about the popular 1983 movie A Christmas Story, which was on constant TV repeat during my own youth.1 It’s a distinctly uncomfortable movie, in a way that I think replicates many of the discomforts of childhood, where you largely cannot choose what you wear, where you go, what and when you eat. Ralphie spends the entire run of A Christmas Story dreaming of a BB gun in the hopes of ending the adult monopoly on violence. His friend Flick gets his tongue stuck to a frozen pole, his mother breaks his father’s beloved leg lamp to preserve her own dignity, he gets his own mouth washed out with soap, while both he and his brother Randy are frequently knocked around by local bullies Scut Farkus and Grover Dill; both Parker boys are repeatedly bundled into hot and uncomfortable outfits and forbidden to take them off.

One of the reasons I suspect A Christmas Story became so foundational to my generation is that it was screened in an uncomfortable way. Both TNT and TBS replayed the movie relentlessly throughout each December in the 1990s; by 1997 they started playing it for a 24-hour-loop on Christmas Eve, so that watching A Christmas Story became as intolerable as childhood itself. At any point in December, you could find yourself swept up in the small-scale sufferings of Ralphie’s Passion; here he is locking himself in the bathroom and being betrayed by Little Orphan Annie, here he is humiliated in a bunny costume, here he is being chased home in the dark, here he is making his little brother cry, here he is dreaming of violence.

When Ralphie isn’t too hot, he’s too cold; when he isn’t afraid, he’s swept up in delusions of grandeur; he’s often charged with responsibility for his younger brother without any real power to enforce the rule of parents in their absence; his only encounters with non-parental authority (the department-store Santa whose elf pushes him down the slide screaming, his teacher who gives his Great Work a C+ and the comment “you’ll shoot your eye out,” which echoes James McNeill Whistler’s line to Mortimer Menpes, “You will blow your brains out, of course”) result in violence and dismissal.

Last week there was an extended conversation about collective responsibility towards children and dogs in public that arose from a tweet beginning, “Small child runs up to [my dog]. I body block and say, ‘Maybe we don’t run up to dogs we don’t know.’” Things quickly, if predictably, turned into a sort of referendum on whether dogs or children have it harder, especially in public, and devolved from there.

Most people, I think, when hearing about such a situation, remember the times when they felt misunderstood and intruded-upon in public, on behalf of their own children or dogs, and interpret the story accordingly; I myself am much likelier to remember incidents where I felt put-upon by a stranger than ones where I intruded on somebody else. I so often want to be understood, and only belatedly, if at all, experience a similar desire to understand others.2

It puts me in mind, strangely enough, of the William Tell story. In case you’ve forgotten, William Tell was a legendary Swiss marksman with the crossbow, whose story is set during the late medieval period, in the early days of the Swiss Confederacy. According to the Chronicon Helveticum, the Habsburgs appointed a man named Hermann as the bailiff of Altdorf; Hermann being cruel and domineering, mounted his hat on a pole under the village linden-tree and demanded everyone bow before it. William Tell, being brave and democratically-minded, refused to do so during a trip to town with his young son, was arrested for it, and tasked with a characteristically-cruel test: He must shoot an apple off the head of his young son in a single attempt, or else they would both be executed. He succeeds, and Hermann asks why he had drawn two bolts, since he had only been permitted one; Tell says that if the first shot had failed, the second bolt would have been for Hermann.

Until recently I was dimly aware that William Tell might not have been a real person, but had no idea that the story of an archer being forced to shoot an apple off his son’s head was itself a popular motif appearing in numerous, non-Tell-related folktales.

The motif even has a name: The apple-shot, from the German Apfelschuss (Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index F661.3, which also includes “Skillful marksman shoots left eye of fly at two miles” and “Skillful marksman shoots meat from giant's hands”). Similar stories are attributed to a man named Toko, who served Harald Bluetooth, in the Gesta Danorum:

One day, when he had drunk rather much, he boasted to those who were at table with him, that his skill in archery was such that he could hit, with the first shot of an arrow, ever so small an apple set on the top of a wand at a considerable distance. His detractors hearing these words, lost no time in conveying them to the ears of the king. But the wickedness of the prince speedily conveyed the confidence of the father to the peril of the son, ordering the sweetest pledge of his life to stand instead of the wand, from whom, if the utterer of the boast did not strike down the apple which was placed on him at the first shot of his arrow, he should with his own head pay the penalty of his idle boast. . . . When the youth was led forth, Toko carefully admonished him to receive the whiz of the coming arrow as steadily as possible, with attentive ears, and without moving his head, lest by a slight motion of his body he should frustrate the experience of his well-tried skill. He made him also, as a means of diminishing his apprehension, stand with his back to him, lest he should be terrified at the sight of the arrow.

He then drew three arrows from his quiver, and the first he shot struck the proposed mark. Toko then being asked by the king why he had taken so many arrows out of his quiver, when he was to make but one trial with the bow, "That I might avenge on thee," said he, "the error of the first by the points of the others, lest my innocence might hap to be afflicted and thy injustice to go unpunished!"

The same happens to the hero Egil in the 13th-century Thidrekssaga and Punker of Rohrbach in, amazingly, the 15th-century Malleus Maleficarum; also Henning Wulf in Holstein and William of Cloudeslee in Northumbria:

‘I have a sonne is seuen yere olde;

He is to me full dear;

I wyll hym tye to a stake,

All shall se that be here;

And lay an apple vpon hys head,

And go syxe score paces hym fro,

And I my self, with a brode arow,

Shall cleue the apple in two.’

There are obviously parallels between the William Tell story and the biblical binding of Isaac, although the Tell version is a burlesque where the Abraham version is a melodrama. Both involve the last-minute aversion of violence towards a son, although Hermann is a straightforward villain in the latter to God’s complicated-ambivalent-inscrutable role in the former. Tell can either split an apple or his child’s skull; Abraham can take a knife to his firstborn or a wild ram. God tests Abraham of his loyalty, but all Hermann tests of Tell is his skill; he can go no deeper than that.

There’s always a fine line between silliness and toughness, especially in stories that depend on a disclosure like “You didn’t realize how much danger you were in/Someone is lucky that I restrained myself,” examples of which include Liam Neeson’s “I have a certain set of skills” monologue from Taken, William Tell’s “The second arrow was for you” reveal, the “Silent Protector” image macro popularized in 2016, the “Humans Can Lick Too” urban legend of the 1980s, the Rambo franchise, and last week’s dog-versus-toddler dispute. There is no discursively satisfying substitute for violence, no guarantee that the description of the violence that might have arisen, had things gone slightly differently, is going to make the dismount instead of falling on its face.3

What William Tell, A Christmas Story, last week’s discussion about who is responsible for restraining children in public, and Abraham and Isaac all have in common is the sense of unease that follows an unrealized possibility of violence. Does violence towards children come from tyrants, from God, from the natural order of things, or from nowhere in particular? Why does violence, or the threat of violence, so often fall on children for the transgressions, errors, and forgetfulness of the adults around them? And how can one impress upon a child the seriousness of the violence they have just been spared, except by intimidating them with a description of the violence that might have visited them, had someone not stood in the breach?

Ralphie wants a BB gun for Christmas; he repeats more than 25 times, in a movie that was often replayed more than 25 times a week throughout my childhood, that he wanted an “official Red Ryder, carbine action, 200-shot, range model air rifle, with a compass in the stock and this thing that tells time.” It’s not part of the motif, but I imagine the sons of William Tell, Egil, Punker, and Helling want a crossbow for Christmas more than anything else in the world.

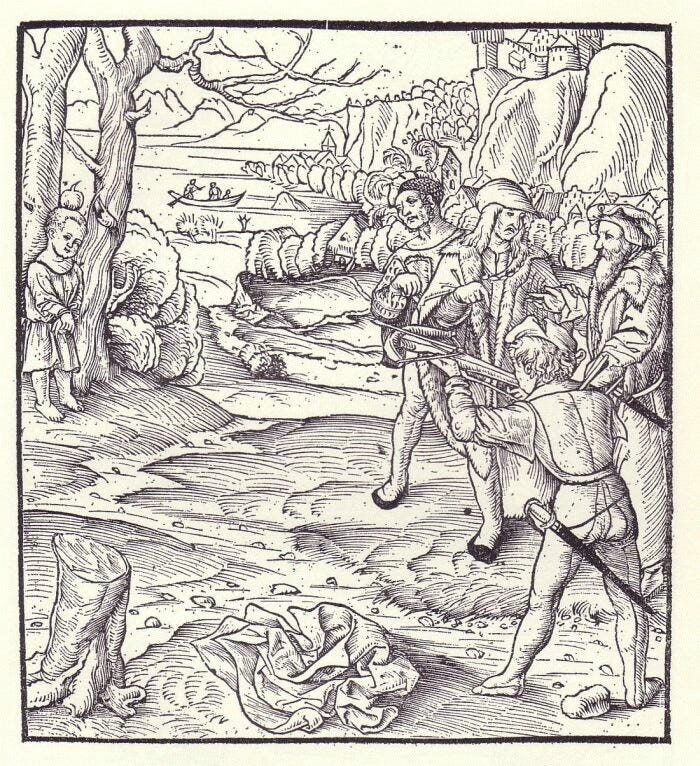

[Image via]

Despite having watched it God knows how many times, I only learned today that it produced three sequels: 1994’s It Runs in the Family, 2012’s A Christmas Story 2, and 2022’s A Christmas Story Christmas; there are also at least four other made-for-TV movies adapting additional stories from Jean Shepherd’s life with titles like The Star-Crossed Romance of Josephine Cosnowski, all of which exist under the umbrella of the “Parker Family franchise.” This man made more off his own childhood than Shirley Temple!

I also think there’s something very memorable and funny about a sentence like “A child ran up to my dog; I body blocked.” It’s pleasing to the ear, if not necessarily to everyone’s judgment.

That’s not to say such avoidance can’t land, or that it’s always silly-sounding rather than successfully-tough-sounding, just that there is no guarantee. Violence isn’t the answer, but nothing else can replicate exactly what violence does.

I was 10 when "A Christmas Story" came out. It instantly became and remained my favorite Christmas movie, because it was the only one that felt REAL. The petty yet all-consuming worries of childhood - homework, bad grades, bullying, weird food, anxious yearning for that one perfect gift that would surely change your life, imagining grandiose scenarios in which you triumphed over all your enemies and they bowed before your clear righteousness - it was like seeing myself on the screen, only substitute every official Garfield product for the Red Ryder BB gun. Every other Christmas movie is too cloying, too preachy - too false. I will always love A Christmas Story for making me feel seen, and for portraying the real horrors and glories of A Child's Christmas in the Midwest!

I've had to body block a child to protect them from my over-enthusiastic dog and I'm sure someone will have to body block mine at some point for a similar reason. If I never have to watch A Christmas Story again I will die happy. Loved this, what a way to start December! <3