"In 1923 I Was Really 'Out'": Valentine Ackland's "For Sylvia"

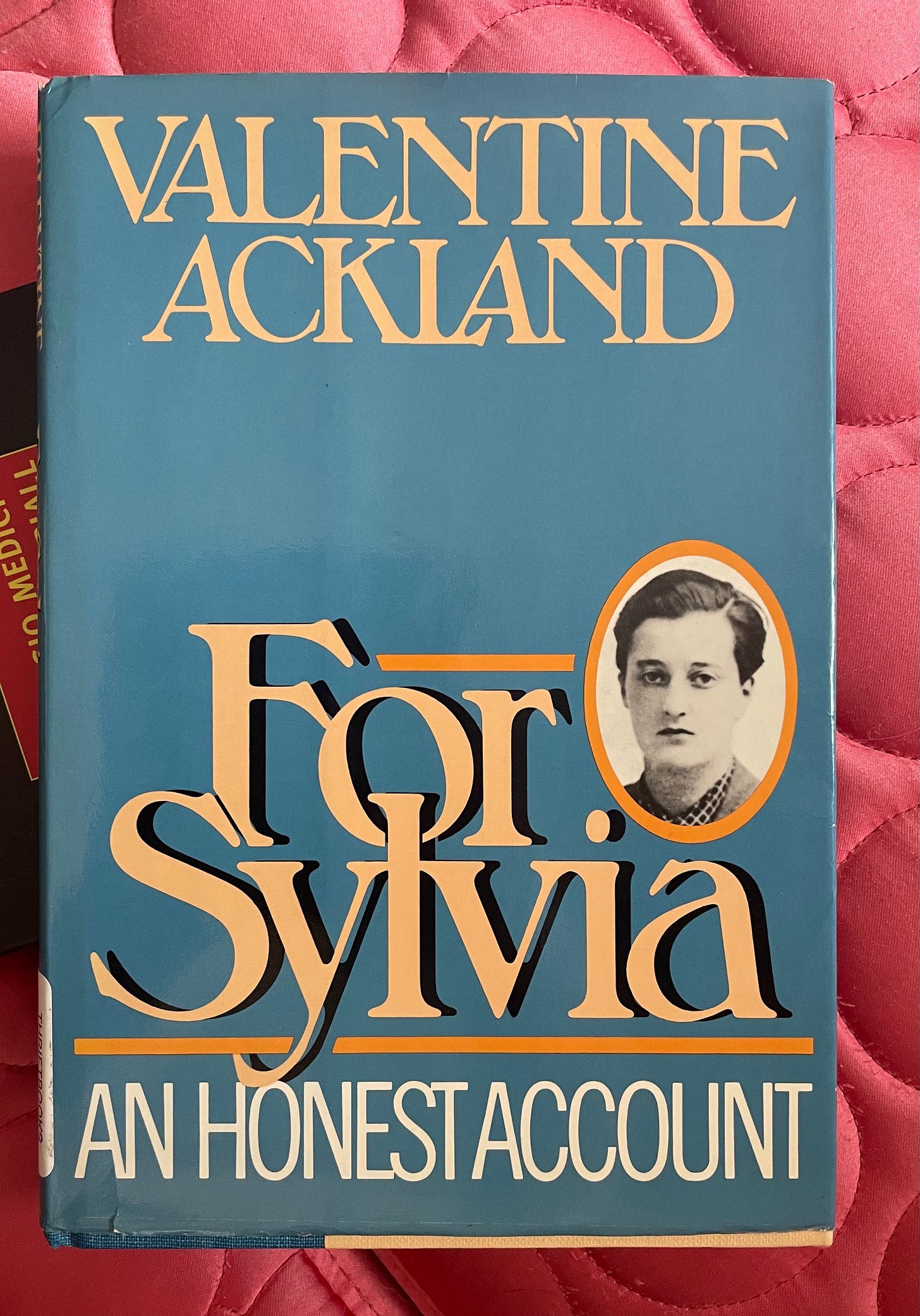

I have an especially soft spot for queer memoirs that are old enough to use “gay” and “coming out” in their original senses.1 Valentine Ackland’s For Sylvia: An Honest Account (written in 1949 and published in 1985) delivers on both fronts:

In that year [1923] I was really ‘out.’ In May of the year I had given a coming-out dance, and now my mother’s insistence that death was nothing to care a straw about gave us a license to live in a riot of dances and parties; more than license — it forced upon us (upon me at any rate) a strange desperation of enjoyment — as though I owed it to her as a duty to be as reckless and assertive as I could manage. That is how it seemed sometimes, at least. And the period favored it.

London was extremely gay, and it was fashionable to commit extravagancies and follies. I remember wearing a bare-backed, sleeveless bright green evening dress and screwing a horn-rimmed monocle into my eye, and walking down the steps into the Savoy Ballroom like that — at the age of seventeen — for a bet. And a fine image of folly I made myself, and desperately shy and ashamed I was of the stir I caused, too. And after all, it ended in paying 10s. 6d. for the right to dance there for three or four hours, and to drink orangeade at 2s. 6d. a time with the young man of twenty who was my partner for the evening. An unsophisticated young man, if ever there was one; who was delighted and a little afraid to be out with such a smart devil-may-care young woman.

And so we drank our orangeade and chattered, as best we might, in imitation of the Bright Young People of that date. And I think we enjoyed it quite fairly, and I know that we enjoyed the act of dancing more than anything else, because we had the skill for it. But we had no emotion whatever towards each other, and indeed, at that date, I had not experienced any physical emotion for any young man, nor responded at all to the few who seemed to be excited by me.

It’s a remarkable book, although unfortunately out-of-print. There are some reasonably-priced used copies available on Amazon and Abebooks, and Handheld Press released a well-received Ackland biography in 2021, so it’s not impossible to think For Sylvia might be due a reissue sometime soon. Valentine’s partner, Sylvia Townsend Warner, has had a number of books reissued by NYRB Classics in the last few years (including the more-than-excellent The Corner That Held Them, an architectural biography of a fictional nunnery that spans several centuries and which I can’t recommend heartily enough), so there’s reason to hope.

Ackland wrote For Sylvia in the months leading up to a carefully-arranged break in their shared domestic life. They had lived together since 1930 quite happily, but from the late 1930s Ackland had also been involved off-and-on with the American heiress and writer Elizabeth Wade White2; in 1949 they decided that White and Ackland would try living together at Frome Vauchurch, Sylvia’s home, while Sylvia herself stayed at a hotel in Somerset.

“I have basely deserted Valentine, though it is by mutual agreement,” she wrote to friend Bea Howe at the time. “She has an American friend staying with her, not an affliction, for she likes her; but so do not I, said the cookmaid.”

To another friend earlier that summer Sylvia had written without trying to make light of the affair:

So in a month or a couple of months Valentine and ————— will be living together. Here, in this house, I hope. It seems much the best plan. It will assure Valentine a continuity of work and trees growing and books, some of her roots will remain in the same ground. It will settle ————— with a certain degree of respectable domesticity, which will be much more settling to her nerves than flitting from hotel to hotel; and for my part, I would rather have the sting than the muffle of staying. But the main reason why I am telling you all this is that for the first time I have been able to feel a living and in-my-flesh belief that Valentine may one day return to me. Til now I have assented to this belief with something more calculating than hope and more tremulous than reason; and chiefly because I love her cannot bear to disbelieve her assurances. But yesterday, I saw her not only more shaken by the news in the cable than I (that could be accounted for by her doubled state of mind, and the burden of two loves she has to keep her balance under) but — what is the word — the word is very nearly appalled. It seemed to me as though this was the first time she had realized herself as living without me, that, until now, solicitude had always presented it to her as me living without her…I cannot tell if it will make the immediate future easier…But it was there and I saw it and so I want to tell you.

For Sylvia is an attempt of sorts to furnish a history of Ackland’s greatest personal struggles — her secret alcoholism, which she calls “dipsomania,” her tortured relationship to Catholicism, her devastating shyness, her failed early marriage — in the hopes of helping Warner better understand her ‘doubled state of mind’:

“I felt released from shyness and timidity, when I was a little drunk, and I became amusing and beguiling. I knew — and as it were I became integrated, together in myself, and possessed myself. I thought that without it I should slip back into being afraid; and I knew instinctively that without that to make me unreal I should see myself as I was, and I dared not.”

The book, which Ackland presented to Warner several months before White’s arrival, has very little to say about White, or about the romantic experiment they were struggling to conduct together, until the very end, which she writes about as an event wholly external to her, like the appearance of a comet:

I write this on a day when I have heard that at any time now another one I love will come to live with me here, in this house where Sylvia and I have lived for twelve years together, through bitterness of private woe, through war, through my degradation and shame and through the almost two years accomplished of my heavenly rescue [the end of her drinking] and our increasing happiness and peace. I do not know how this new thing has come about, nor whether it is the work of heaven or hell. I cannot, for more than a moment at a time, realize what it will be like to be here without Sylvia — or anywhere without Sylvia. But I have a conviction that this must be tried; although it is so dangerous that I can scarcely dare measure it even in my fancy.

The experiment was brief, and certainly from Sylvia’s perspective successful. She had left Frome Vauchurch to make way for White in September, then returned in October after White’s departure; Warner and Ackland remained together until Ackland’s death in 1969. Though they would remain seriously at odds over Ackland’s periodic return to religion (first to the Catholics and later to the Quakers), the great crisis had passed; there was no danger of the horse bolting from the stable (or, more accurately, the stable discreetly decamping from around the horse) a second time.

“One’s life is so very long (I am forty-three as I write this); one’s experience so much; it is as if one were a cistern, filled by the rain running off the roof; very clear and cool and pure, always, the water that runs in, and it is not very often that any is drawn off; and it is as if the cistern, which is oneself, were thinking sometimes of the first showers of rainwater that ever flowed in — how miraculously cool and soft and valuable that water seemed; how little there was, safely stored there in one’s own dark depths; and then more and more rains, showers or storms or drizzling downpours; and what has happened to that first, that purest of all cool waters? Lying right down at the bottom, one might think if one were a cistern; it will never be drawn off — never — never — and yet, the tap (if anyone comes to turn it) is right down at the bottom, and that is the very layer which is first drawn off.

As if water remained stored in layers! But that is how my mind works, taking images and setting them a little awry.”

“Lighthearted and carefree” and “A young woman’s formal introduction into society,” respectively.

In 1939, Ackland also had an affair with White’s partner, Evelyn Holahan.

This is so beautiful.

Often when I encounter earlier written accounts of queerness I feel this hollow sort of sadness that some other feeling echoes inside. Something very much akin to "as if water remained stored in layers!" but in terms of how I think about history.

Lbr if queer memoirists didn't write so frequently of their own afflictions with alcohol it would have taken me way longer to recognize it or feel comfortable acknowledging it in myself so another big soft spot there, yes we love to see it! thanks for sharing