Sibling Vs. Only Child Cinema: You Never Meet Anyone New in Beauty and the Beast

If the blonde triplets who share Belle's face and deride her sexual object choice aren't older-sister-coded, I'll eat my hat

I saw two movies this week: All Of Us Strangers and the 1946 Jean Cocteau version of Beauty and the Beast, both of which were new to me, and both of which struck me as significant examples of experiencing the world as an only child versus as part of a group of siblings.

I’d felt both skeptical of and compelled by the All Of Us Strangers trailer when I saw it a few months ago.1 I worried it would be mawkish; I worried it would overwhelm me. I worried I would find it dishonest or manipulative, and I worried that it would nonetheless make me cry.2 I’m sometimes afraid that I will be moved by ‘the wrong thing,’ especially when it comes to movies; I want to learn what the majority opinion is first so I can calibrate my own emotional response to match it.

Some of the elements about AOUS which had initially put me off made more sense to me when I considered them in the context of “sibling cinema.” Andrew Scott’s Adam spends most of the movie experiencing the curiosity of others without reciprocating. His revived parents and his young lover Harry are all incredibly interested in him. They’re solicitous of his welfare, they want to know his habits, his preferences, and his plans, they want to know how he’s feeling, about them and about life in general, they want to offer him advice or admonition or drugs or all three at once. They don’t often volunteer information about themselves, and he doesn’t often ask. He cares about them, hugely and visibly, but like them he is mostly curious about his own inner experiences.

At first I found this disconcerting — I wanted Adam to “behave better,” to ask more questions of them in his turn, as if I had been tasked with reviewing his social conduct — but I think it communicates a certain kind of only-child experience I find interesting. Adam has no contemporaries, no colleagues, no friends his own age; at 52 he is older than both his twentysomething lover and his ghostly parents, who died in a car accident when he was eleven.

“What do you think we should say to each other?” Adam’s father asks at their first reunion. “I’m not sure I have much wisdom to share. Maybe Adam, being older, should be sharing some with us.”

Both my partners, Grace and Lily, were only children (they still are the only children, I should say, only they are no longer only children, if that makes sense); as the middle child of three I find the concept of being an only child totally fascinating. I’m sure there are as many different ways to experience only-childhood as there are only children, but it must be remarkable, having that kind of uniquely focused and unshared adult attention on you from jump. Besides which there’s something rather grand and fairy-tale-ish about the expression “only child,” as if the only remaining child in the world. Even a very popular only child, possessed of an army of cousins and close friends and other child-allies, is at home either matched or outnumbered by the adults, and can never hope to form part of a majority.

Both my partners were also gay only children, so they were outnumbered twice over by heterosexual adults; in this way it makes sense to me that Adam, the overdetermined only son of vanished parents, experiences the world in All Of Us Strangers as a relentless series of questions, inquiries, reassurances, reunions and repeated goings-over of the past. He is the key to everyone’s past and the bridge to everyone’s future; it’s not possible for an only child to share the psychic weight of family relationships with a contemporary.3 They experience relationships upwards and downwards long before they get a chance to do so laterally.

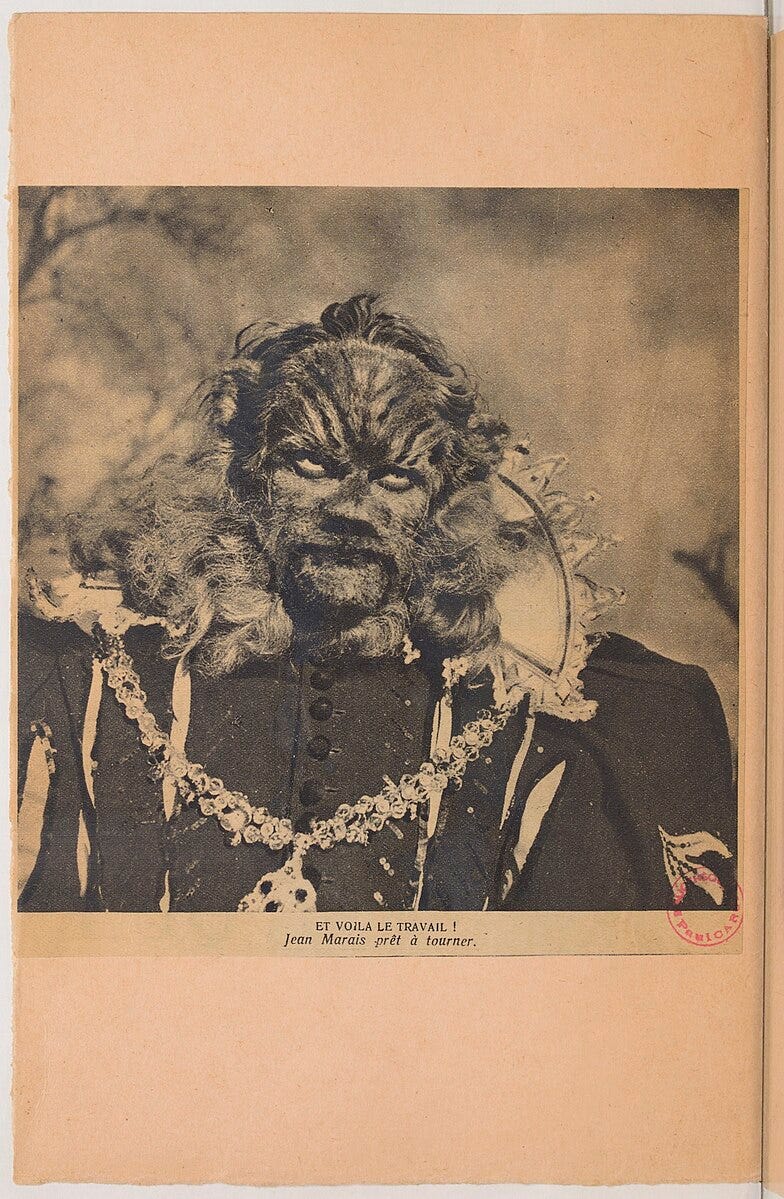

Strangely, in both All Of Us Strangers and La Belle et la Bête it’s sort of functionally impossible for the protagonist to meet anybody new. Adam’s new lover Harry is the only other resident in their otherwise-empty high-rise on the outskirts of London; they already live together before they meet one another, and outside of Harry and a mostly-unseen waitress, Adam doesn’t see anyone else besides the ghosts of his parents for the whole movie. He takes the train back and forth between his apartment and his childhood home, and that’s it. Beauty and the Beast has a sort of Peter Pan-style stunt casting (where traditionally the roles of Mr. Darling and Captain Hook are shared by a single person) whereby the same actor, Jean Marais, plays Avenant, a friend of Belle’s brother and her first suitor, as well as the Beast (both before and after his transformation). Belle moves from her father’s house to the Beast’s house, back to her father’s house and then again to the Beast’s (by the end of the movie she’s moving faster-than-light between her bed in each house), but she only ever talks to the same men in different outfits.

But Beauty and the Beast is a classic sibling story. (The 1991 Disney animated adaptation is, I think, the only version where Belle is given no brothers or sisters, unless you count the mysterious blonde triplets who share her face and deride her sexual object choice, which you have to admit is awfully sister-coded of them.)

In the 1946 Beauty and the Beast Belle has a feckless, affectionate brother and a feckless, needy father, both of whom accumulate debt like it’s a birthright, and a pair of older sisters who are nearly indistinguishable from one another, and absolutely weapons-grade bitches to boot.

Interestingly, Avenant is introduced alongside Belle’s brother Ludovic and is hardly ever separated from him. It took me a little while into the movie to realize that Belle didn’t have two brothers, because in every way but proposing marriage Avenant behaves like a brother does. No one ever says “Avenent, you should go home, this is a private family moment.” He’s as automatically included in their moments of deepest shame and humiliation, when their furniture gets repossessed to pay their bills, and teases the two eldest sisters (Félicie and Adélaïde) as if they were his own sisters.

Félicie and Adélaïde, like all vicious fairy-tale sisters, are hard not to love. They possess irony, teamwork, excellent taste, ambition, rage, desperation, psychological complexity, and political solidarity. They say marvelous things like “Just look at this drunkard. He doesn’t even know his proper role in society. A barefoot guttersnipe!”

(Incidentally, Belle’s sisters are of course right to abuse her for being the architect of their misfortune; asking for a ‘single rose’ when a merchant is heading into town is infinitely more complicated than asking for jewels or a new hat. Sisters make for very exact measurers, like a dressmaker or a bird of prey; they can spot a millimeter of “Oh, so you think you’re better than me?” from a mile away.)

But I have a soft spot too for a beautiful simpleton whose only drive is towards self-abasement! Cocteau’s Belle wears conspicuous martyred drudgery like a peacock wears his tail; it alerts every man within eyeshot to her superior fitness as a mate while simultaneously driving every woman to try to claw her eyes out. We first see her polishing the floor in her sister’s room, after they’ve grandly swept out the front door in ostrich-plumed hats and neck ruffs a foot wide. She doesn’t so much fish for compliments as she shoots them out of a barrel:

AVENANT: Belle, you weren’t made to be a servant. Even the floor longs to be your sister! You mustn’t go on slaving day and night…Why don’t your sisters work?

BELLE: My sisters are too beautiful. Their hands are too white.

AVENANT: Belle, you are the most beautiful of all! Look at your hands.

BELLE: Avenant, let go of my hand — Please go — I must finish my work.

In real life, of course, Belle knows better than to waste any of her kindness or sympathy on her sisters, or indeed on women in general. They hate her and she blanks them. Belle graduates from the school of understanding her father to being awarded with trying to understand the Beast, the most difficult and complicated man in the world. She knows better than to accept Avenant’s premature marriage proposal because she is not willing to be anything less than the most important woman in the world, much less the house — he thinks she’s working too hard and wants to get married so she can relax. “If our father’s ships hadn’t been lost in the storm,” she tells him, “then perhaps I could enjoy myself like [my sisters].”

But to relax would mean never again being stopped in the middle of scrubbing a floor, told the floor itself wishes it could reflect your exquisite beauty, that you’re a saint who is wasted on the brutes around you, that you’re more beautiful than anyone else, that everyone else is putting on airs while you are air itself. Belle knows better than to trade down; like Jane Eyre, she knows what side her bread is buttered on. The Beast is a good trade for her father, because he’s even more despairing and vulnerable, and her virtuous self-denial and prim horror shines even more brightly in his setting. Avenant is handsome, happy, and doesn’t want her to abase herself. What good is that to her?

Once she’s ensconced in his castle, Beauty and the Beast face off in a competition of dueling Munchausen’s. Both of them get sick and threaten to get still sicker if they don’t get their way. Her father gets sick, so she will get sick unless the Beast lets her go home to see him; the Beast will let Belle go, but now he is going to get sick as soon as she leaves him, and will even die if she fails to return on time. A broken animal is the only husband Belle would ever consider leaving her father for; she is satisfied. It’s only once the Beast proves he can be even needier than her own father that she begins to reciprocate his feelings for her.

Cocteau famously understood the Beast’s final transformation as a disappointment:

“My story would concern itself mainly with the unconscious obstinacy with which women pursue the same type of man, and expose the naivete of the old fairy tales that would have us believe that this type reaches its ideal in conventional good looks. My aim would be to make the Beast so human, so sympathetic, so superior to men, that his transformation into Prince Charming would come as a terrible blow to Beauty, condemning her to a humdrum marriage and a future that I summed up in that last sentence of all fairy tales: ‘And they had many children.’”

At precisely the right moment, Avenant trespasses into the Beast’s garden and is himself changed into a beast before dying; the Beast, nearly dead, springs up as Avenant, now wearing princely clothes and if anything looking smugger and more self-satisfied than before. Her disappointment (among other things, she now has competition, instead of being a prized non-pareil) is obvious:

THE PRINCE: Love can make a Beast of a man. It can also make an ugly man handsome. What is it, Beauty? Do you regret my ugliness?…Does my resemblance to your brother’s friend displease you?

BELLE: Yes…No.

THE PRINCE: Are you happy?

BELLE: I shall have to get accustomed to you.

After this she is air-lifted out of the plot and her family, never to return.

In a sibling movie, no one is curious about anybody else, but everyone compares notes and updates their alibis accordingly to get one over one another. The only real prize is marrying out, and the kid with the best image management wins.

The last scene which includes Félicie and Adélaïde shows them stealing Belle’s enchanted mirror to look at themselves; they see a hag and an ape, respectively. They both cry out in fear, but neither will admit to the other what they’ve seen, since any child with a sister learns early to never say anything which may incriminate herself.

“What can you see?” Adélaïde asks, eager to spread the misery around.

“Nothing,” Félicie says. “Let’s take it to Beauty. It’s her turn.”

[Image via]

On the more compelling side: I think Andrew Scott winces (albeit in a different register) about as well as any movie actor since Humphrey Bogart, the last of the really great wincers. On the more skeptical side: I generally dislike time-travel-related plotlines because I think they often produce a cheap sort of emotional bypass that I especially resent because they work so effectively on me.

I haven’t yet read Strangers, the book it was based on, nor seen its 1988 horror adaptation The Discarnates, although now I’m looking forward to doing so.

I mean as an only child, while they’re growing up; I certainly don’t mean that anyone who has been an only child doesn’t know how to relate to other people laterally or anything like that.

The recent-ish Italian movie The Eight Mountains was the most only child-ass movie I, an only child, have seen in many a year. What AOUS misses is the threat of the only child, to have all the attention taken away from you and bestowed on another, although it does nail the particular devastation of disappointing your parents when you're the last of the line.

The only time travel parent feelings movie for my money is Petit Maman. The parents are the least interesting thing about All of Us Strangers