They Don't (Re)Make 'Em Like That Anymore: Formerly-Popular Hollywood Remakes

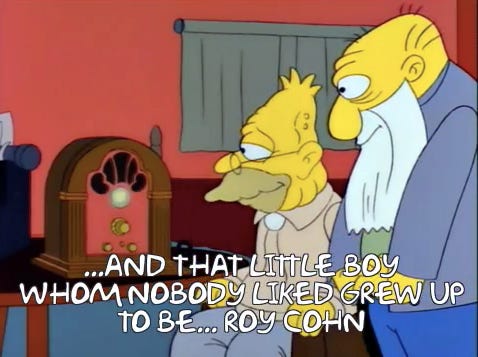

I came to a number of widespread-but-already-fading 20th-century cultural touchstones indirectly — as I think did many of my generation — mostly through Peanuts and The Simpsons. The first time I heard the Roy Cohn gag in the “Homer’s Barbershop Quartet” episode (season 5, aired 1993), I didn’t know who Roy Cohn was, but I understood the cadence of the joke and the implication of the old-fashioned radio.

I’d never actually seen a radio like it in real life, but it looked like the old-fashioned radio I’d seen in annual reruns of A Christmas Story (1983), and I was able to cobble together a reasonably-informed laugh through context clues derived from growing up in the wake of Baby Boomer cultural nostalgia. I didn’t know who Rory Calhoun was either the first time I saw “Two Dozen and One Greyhounds,” or for many years thereafter, but I didn’t need to know in order to find “You know — that person who’s always standing and walking!” followed by a tentative “…Rory Calhoun?” funny. “You know who I mean, that guy” is a comedy routine I’ve never tired of, nor ever shall.

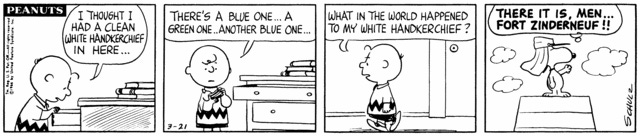

I felt the same way about Snoopy’s frequent sojourns to “Fort Zinderneuf,” even though the figure of the tortured French Legionnaire was totally alien to me. The World War I flying ace was only slightly less alien, but for whatever reason the Sopwith Camel and Red Baron left me totally cold — if I could have sent back the Sunday comics featuring that storyline like a tiny diner rejecting an insufficiently clear consommé, I would have. I had no primary sources for the tortured mercenary, only a copy of decades-old parodies, and would have to work my way backwards. It was the sort of puzzle I liked, reading by inference, along with trivia questions word scrambles, Scattergories, MathBlaster!, anagrams, ciphers, spot-the-difference pictures, Headline Harry and the Great Paper Race, and Microsoft Encarta’s MindMaze (the sort of puzzles I did not like is a much longer list, including, but by no means limited to, crossword puzzles, cryptic crosswords, Scrabble, jigsaw puzzles, Wheel of Fortune, Magic Eye illustrations, Sudoku, the Monty Hall problem (inclusive of all Marilyn vos Savant columns in Parade Magazine, mathemagicians, Sideways Arithmetic From Wayside School, probability problems).

One of the reasons I’ve always liked old movies (particularly from the 1920s and 1930s) is the opportunity to see Victorian and Edwardian themes carried over into mass-media of a type I was already familiar with. So I was able to work my way backwards from Peanuts’ “Beau Snoopy” character to the 1939 version of Beau Geste, the one with Gary Cooper.

This version was itself a remake of the silent 1926 adaptation starring Ronald Coleman and Noah Beery, Sr. (retroactively familiar to me from having seen his younger brother Wallace Beery in The Champ and Grand Hotel and his son Noah Beery, Jr. in Only Angels Have Wings and Flight at Midnight, rather like how I stopped in shock on my first viewing of Errol Flynn’s Robin Hood1 to ask, “Why is the Skipper in this movie?”).

The ‘26 adaptation came two years after the publication of the novel by P.C. Wren, and was subsequently remade in 1966 with Guy Stockwell (a version I’ve never seen) and in the early 1980s for the BBC, as well as onstage at the Campbell Playhouse in 1939 with Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles (!). Wren’s sequels, Beau Sabreur and Beau Ideal, were each adapted only once. Beau Sabreur is lost except for the original trailer. Beau Ideal is free to watch online, although most streaming versions have indifferent-at-best picture quality. Judge for yourself:

It was just as often adapted as parody2, as in the (dreadful, in my opinion) 1931’s Beau Hunks starring Laurel and Hardy, as the equally-dreadful Follow That Camel in 1961. If you’re flexible on the subject of interpretative remakes, you might also include 1950’s Abbott and Costello in the Foreign Legion, Laurel and Hardy’s Flying Deuces remake of their own parody in 1939, and 1928’s originally-silent, partially-wired-for-sound Plastered in Paris.

Then there’s Marty Feldman’s version, released in 1977 as The Last Remake of Beau Geste.

He was almost right, too, aside from the ‘82 BBC miniseries. Beau Geste remakes have gone the way of CinemaScope and DiscoVision. What remains of the Beau Geste legacy is scattered and informal, a few freestanding ruins to suggest an ancient organization. British ornithologist John Krebs coined the “Beau Geste hypothesis” in 1977 to “explain the apparently redundant song repertoires of many oscine birds” in order to assess residential density “to increase the apparent density of singing residents, and hence decrease the apparent suitability of the area to new birds,” citing the then-familiar scene in Beau Geste where the legionnaires prop the bodies of their fallen comrades against the fort they’re attempting to defend and place rifles in their dead hands, to create the illusion of an inexhaustible fighting force. The term has been similarly applied to small coyote packs howling in “rapid tonal shifts” to create the impression of a much larger group.

Dune seems to have replaced Beau Geste for extravagant Orientalist fantasies as if by fiat (the first abortive Jodorowsky remake was kicked off in the early 70s, followed by Lynch and De Laurentiis’ version in ‘84, five video games, a board game released first in 1979 and again in 2019, a collectible card series and an officially-licensed RPG, the Sci-Fi Channel miniseries in 2000 and 2003, the recent Villeneuve version. Do read Max Read’s annotation if you have the time; it’s quite good). There seems to be a boom-and-bust cycle to adapting Orientalist adventure fiction of the 1890s-1930s; for every successful Tarzan and Greystoke there’s a flop like John Carter, for every enduring genre like the Ruritanian romance there’s a short-lived heyday like Spaghetti Westerns (Django Unchained notwithstanding). Cold War thrillers, both of the more meditative and melancholic Le Carré type and the good-guy-with-a-gun Tom Clancy type seem to have taken over the exploration of late-stage-colonial-project anxieties, while 24 and other spiritual successors to Rambo like the Olympus Has Fallen series and White House Down (plus whatever direct-to-video Seal Team Six fantasies John Krasinski is starring in nowadays) handle the tortured-mercenary-turned-imperial-asset front.

Incidentally, the French Foreign Legion still exists and has a formal website; this shouldn’t be any more surprising than any other official military website, and yet there’s something unexpectedly jarring about it. Part of the colonial epic’s responsibility is to regenerate the colonial story, to treat new incursions as if they were happening for the very first time, so any reminder of the recently-scrubbed past is like stumbling onto a family reunion group for Hapsburg descendants on Facebook, or marrying your own grandfather.

Future installments of this series will take a look at the “College Widow” in Horsefeathers and elsewhere, the Tennyson poem that might hold the world record for number film versions, and the rise and fall of the generation ship in science fiction. If you have any particular favorite out-of-date movie trends, I’m happy to take recommendations.

Alan Hale, Sr. might hold the record for most onscreen portrayals of Little John, having reprised the role in the 1922 Douglas Fairbanks version, the aforementioned 1939 version, and in 1950’s Rogues of Sherwood Forest. Lord love any actor who starts looking like he’s in his 40s in his 20s and continues to look like he’s in his 40s until his death.

Two other newspaper comics besides Peanuts spoofed Beau Geste, one British (Beau Peep) and one American (Crock); additionally there was a 1939 spoof starring Porky Pig I’ve never seen but can imagine with what I’m pretty sure is 99% accuracy.

i, too, was a child of the late 20th century with a lot of dated cultural touchstones looming large in my head - partly through Peanuts and the Simpsons but also because i loved old paperback MAD Magazine collections i found at used bookstores, cassette tapes of old-timey radio shows, and, yes, crossword puzzles, which until pretty recently were often premised on the idea that the person doing the solving was born in 1937. i think the 80s were a really peak time for that sort of backwards-looking culture - what with the President being a washed-up 1940s movie star, among other things.

(somewhat related: i am often struck by the relative gaps in time revealed in considering pop culture. see, for instance, the way the Indiana Jones and Star Wars movies are considered a major touchstone in themselves, but for their creators were loving homages to the serialized B-cinema of their youth. a time-equivalent version of "The Wedding Singer" released now would take place in 2008.)

It's a recurring conversation between my Dad and I anytime I reference something way too old. "Where you'd hear that?" "Probably The Simpsons, or Animaniacs, or that one episode of Wishbone..."