"You Should Call Your Father": On the Unbearable Estrangement of Other People's Families

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein describe in The Final Days Richard Nixon’s reaction to his loss of power: “Between sobs, Nixon was plaintive...How had a simple burglary done all this?...(He) got down on his knees...leaned over and struck his fist on the carpet, crying aloud, ‘What have I done? What has happened?…’”

I must admit to a great weakness for rare and peculiar events. As we shall see, one of my chimpanzees had tantrums similar to Nixon’s (minus the words) under similar conditions.

-Frans de Waal, Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes

Over the last few years, particularly since my own somewhat-public estrangement from my family, I’ve advised a sizable number of advice-seekers (first as Dear Prudence, later and on a much smaller scale, as part of the Big Mood, Little Mood show) to earnestly consider severing ties with their own. Like attracts like, of course, so I’m likelier to hear in the first place from people with very serious, weighty troubles like interfamilial abuse, extreme homophobia and transphobia, untreated alcoholism or addiction, cruelty or neglect, that have led them to consider estrangement. It’s a slightly surreal circumstance, as I don’t go about championing widespread estrangement as a first order of business in my daily life, but I’m likelier to hear from people who have already unsuccessfully tried a series of milder interventions and fear they’ve exhausted other possibilities.

I do think there’s often a case to be made for forbearance, for taking people as they are and accepting their human limitations with cheerful tolerance (even one’s parents!) as much as possible. And the last fifty or so years have seen a remarkable shift in how much hard vs. soft power the average parent can wield over their children in this country — the forces of tradition, public opinion, corporal punishment, and economic influence that once operated primarily in parental favor have largely declined, such that the ability to command has often given way to mere suggestion, hope, insinuation, persuasion, bargaining, attraction, or wheedling. I don’t wish to underestimate the scale of the change from what a child in the 1950s or ‘60s might be taught that they owed to their parents versus what they expected of their own children in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and what those children in turn thought was a fair estimation of what they owed to them. And who, whether parent or child, doesn’t hope to be understood by others, doesn’t hope to receive the benefit of the doubt, doesn’t wish to be seen in a friendly and sympathetic light?

For obvious demographic reasons, I mostly hear from adults (some young, others not-so-young) contemplating estrangement from one or more parents, sometimes an entire branch of their family; I very rarely hear from adults considering disowning or ending a relationship with an adult child, and almost never from an adult whose grown child has stopped speaking to them.

Recently I received a letter from someone who doesn’t quit fit into any of those categories, from a parent whose grown children speak to her, but one of them recently shared a critical (or, more accurately, a wistful) thought about her husband; seemingly as a result of this conversation, the letter-writer believes I should stop encouraging other people to consider family estrangement as a viable possibility. The logic is a bit tortured, but I think it’s a useful glimpse into a certain parental perspective that simultaneously fears estrangement above almost all things, and creates all the necessary preconditions for its inevitability.

I have been listening to your podcast that discusses a letter that you received where the writer is asking about estranging her father. As a parent (mother) I am absolutely horrified at the glib insensitive discussion that you and your cohost are taking.

Estrangement seems to be the new behavior of the day that young adults use to deal with their parents. Often the story goes much like the one described by the person who has written in: in therapy someone has unearthed how insecure they are. This problem gets chalked up to a failure on the part of the fallible parents who then receive the blistering response to their efforts as a parent to being excommunicated. Goodness knows in my generation the idea that churches could do this to their parishioners for breaking the rules was considered such an unacceptable practice of condemnation. I am appalled at the number of internet/podcast personalities that just glibly suggest that this is okay. I am also really surprised that therapists might recommend this to anyone but the most severely mistreated.

There’s an interesting elision in how she describes the letter in question: “Often the story goes much like the one described by the person who has written in: in therapy someone has unearthed how insecure they are. This problem gets chalked up to a failure on the part of the fallible parents.”

The letter in question is from the February 8th episode with Marie Manner. Here’s how the original writer describes her relationship with her father:

I’m in my late 20s, and I’ve been in therapy for a few years now for anxiety, shame, and self-esteem issues, as well as a history of abusive relationships. My therapist attributes this to childhood emotional neglect and authoritarian parenting on the part of my father. My father is an emotionally-repressed narcissist who has never taken an active role in my life. He gaslit me, shamed me, criticized me. He constantly called me lazy, ungrateful, entitled. Sure, he met my material needs, but there was no emotional intimacy, acceptance, or love.

For what it’s worth, I was also curious about the first letter-writer’s decision to attribute her father as the source of her anxiety and shame via her therapist, and asked her to consider whether she herself agreed with her therapist’s assessment, or whether she thought saying “my therapist” lends credibility to her perspective she fears she doesn’t have on her own.

But it’s fascinating to see how “anxiety, shame, self-esteem issues…emotional repression…never taken an active role in my life…shamed me…constantly called me lazy, ungrateful, entitled…there was no emotional intimacy, acceptance or love,” which describes a pretty consistent, painful pattern of degradation and alienation, lasting decades and affecting her relationships with other people outside the family unit, is in the second letter-writer’s summation reduced to “how insecure they are.” If that had been the original writer’s sole explanation for why she no longer wanted a relationship with her father, I might have agreed with the second writer about the arbitrary glibness of such a decision – but of course, it was not.

I’m not sure of the second letter-writer’s generation, either, but it’s surprising to see the claim that “the idea that churches could do this [excommunicate] to their parishioners for breaking the rules was considered such an unacceptable practice of condemnation,” when churches in fact invented the procedure of excommunication (or disfellowship, or formal shunning, depending on the denomination). Regardless, I would not encourage any letter-writer to model their decisions concerning personal relationships on church disciplinary practices.1

The second letter continues:

The job of being a parent is long, complicated, and requires enormous amounts of self-sacrifice. The idea that anyone would recommend this [estrangement] to anyone else without knowing in pretty specific detail the ins and outs of the relationship is shocking to me. It shows a complete lack of sensitivity to the person writing let alone the parent. First and foremost every human on the planet should approach each other with empathy and kindness. This goes for complete strangers and god forbid, our parents. As Atticus Finch said we should all consider what it might be like to walk in another man’s shoes. This man sounded terribly hurt that he was unable to walk his daughter down the aisle. I have been with my husband for forty years. He is one of the kindest, most considerate people that I have ever met, but he is human.

It is clear that this letter-writer feels confused and left behind by a seemingly culture-wide shift in values, where stability and respect have been traded for impatience, entitlement, and the attitude that other people ought to make you feel good 100% of the time, or else be shown the door. I don’t doubt that her grief and alienation are very real. And I certainly agree that compassion, imagination, and perspective ought to guide us in our interactions with other people, whether they be strangers or close relatives (and I certainly fall short of this standard in my own life as often as not). But I can’t agree that personal estrangement is necessarily the opposite of empathy and kindness, nor that “recommending” estrangement to someone in the original writer’s position necessarily requires taking an exhaustive history.

It helps, I think, to clarify the role of the internet stranger/advice columnist in such a position – because I have no idea who any of my letter-writers are, and because we play no direct roles in one another’s lives, there’s a great deal of freedom in offering my (necessarily limited, but not necessarily wholly-irrelevant) perspective, since they can just as easily ignore it as take it. I’d be very surprised indeed if someone felt strongly committed to a particular course of action, then decided against it solely on the strength of a single advice columnist’s opinion. I don’t believe I could convince any letter writer committed to maintaining a relationship with their parents to become estranged from them instead, no matter how persuasively I spoke, or how bleak a spin I placed on their connection.

The second letter-writer seems to think that too many young people today consider estrangement too lightly. I am biased in the other direction, and think that most people, by the time they get around to writing to me on the subject, have agonized over the possibility of estrangement for ages, and even tried to put it off for as long as they can possibly bear it. Most people, regardless of the fitness of the relative in question, have a pretty strong desire for parental approval, affirmation, and fondness; that desire is not easily quelled after an argument or two, or the idle realization of a few insecurities in therapy. But I don’t want to preclude the possibility of this second letter-writer being right here! I can certainly imagine any number of situations where an adult child might casually ignore or even end communications with a sincerely affectionate parent, and would be prepared to agree with the letter-writer that such situations would be painful almost beyond description for the parent in question. I don’t believe the letter she references falls into that category, but that doesn’t mean it never happens. Were I being asked for advice by a parent in such a situation, I would encourage them to grant the child their space — even someone who cruelly or unreasonably ends a relationship ought to have that boundary respected; nothing good can be gained from repeated begging — to mourn their loss with sympathetic and supportive listeners, to build up strength and comfort in other areas of their life, and to leave the door open in hope of a possible reconciliation in the future.

But it is this last paragraph, of course, that proves most illuminating:

Recently my son told my daughter that my husband wasn't emotionally accessible enough. My thought with this was that my husband had spent over 30 years putting his feelings aside to provide for his family. Maybe it was hard for him to be emotionally accessible after putting his feelings aside for so long. I hope that in the future on your podcast that you will consider recommending to everyone who writes in that they have compassion for everyone in their lives, whoever they may be. In a culture where we have achieved a level of introspection when it comes to strangers of all different stripes be it racial or sexual orientation etc, and rightly so, kindness with all matters, don't you think that it might be nice if parents, who may have given everything that they could to love their children, that they might receive a little compassion as well?

I can’t be sure, of course, but my best guess is that the daughter relayed her conversation (possibly entered into in confidence) with her brother to their mother, which means that this mother is working with second-hand information about a third party. That’s always a tricky position from which to render judgment — and I mean that sincerely, since that’s often what I’m called upon to do as a part-time internet advice columnist.

But it strikes me as an especially ineffective reaction to this information, especially because “emotionally inaccessible” implies a real, earnest desire for closer communication, rather than a determination to turn away from the relationship. If one hears from one’s daughter that her brother considers their father emotionally inaccessible, I can imagine a number of possible reactions, such as:

Discouraging one’s daughter from coming to a parent as a referee (“Did your brother encourage you to share this with me? I hope you wouldn’t break a confidence without telling him first — I hope the two of you can find a good way to discuss this together, and of course if your brother would like my advice or input, I’d be happy to give it when asked”)

Asking one’s daughter if she shares her brother’s view of their father, and being genuinely open (compassionate, even!) to hearing an assessment of their childhood that might be at first difficult or painful to hear

Asking one’s son if he’s open to discussing the subject with you in the interest of getting to know him better and establishing a new kind of closeness as adults that does not depend upon the younger generation always adapting to accommodate the elder

Encouraging your son to talking about this directly with his father

Talking about this (discreetly and cautiously) with your husband yourself — where did you get the idea that a parent must “put [their] feelings aside to provide for [their] family? Are those your husbands’ words, or yours? You say “maybe it was hard for him to be emotionally accessible” after the children were grown and no longer needed to be provided for, which suggests speculation — why not ask your husband if he finds it hard to access his emotions?

Any of these would be better, more relevant choices than writing to an advice columnist and asking them to stop suggesting other people consider family estrangement. If I cut my finger in the kitchen, I’d better disinfect the wound and put a bandage over it, not write to the nearest hospital and ask them to stop amputating other people’s gangrenous limbs, which is what this letter amounts to.

Perhaps most interesting is that this letter-writer is not (yet, at least) faced with the possibility of a family estrangement. She is faced with instead quite the opposite — it sounds like one of her children very badly wants to have a conversation about how their parents relate to them, and desires a closer emotional connection with at least one of them. That might involve some difficult, even painful conversations, but all in the service of greater future intimacy. Accepting the possibility that one may have hurt a child even with the best of intentions is not the same as saying, “You’re right, I’m [or in this case, your father] the worst parent in the world, I did everything wrong and you did everything right; you’re good and I’m bad.” Perhaps it was not necessary to set aside one’s entire emotional personhood in order to bring home a family wage! Acknowledging that possibility now does not mean putting on a hairshirt forever, and I wouldn’t advise any letter writer, regardless of their age or family position, to adopt such an all-or-nothing approach to hearing loving criticism.

This letter-writer’s son is, in effect, saying he feels all too estranged from his father — there’s a genuine opportunity here to get to know one another better, to soothe some of the hurts of the past, to meet an adult child on a new footing of reciprocity and mutual respect, and I would be very sorry indeed if the letter-writer missed it entirely, becoming so wrapped up in defensiveness and self-pity she mistook an olive branch for a battle standard.

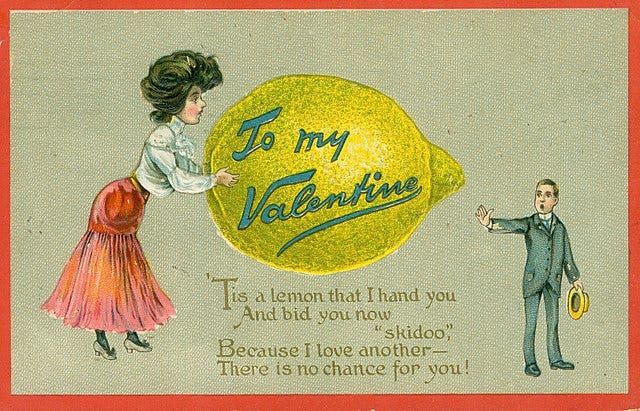

[Image via]

My latest book, Dear Prudence is on sale April 4th. It's an anthology-slash-retrospective of my tenure as Slate’s advice columnist from 2016-2021. You can pre-order your copy here.

Although as a lifelong churchgoer, the second letter-writer is no doubt aware of the Matthew 18 model for conflict resolution within the church, which does in fact leave room for estrangement/shunning as a final resort, and which the original letter-writer actually seems to have fairly closely, if unwittingly, followed already: “If your brother sins against you, go and tell him his fault between you and him alone. If he hears you, you have gained your brother. But if he will not hear, take with you one or two more, that ‘by the mouth of two or three witnesses every word may be established.’ And if he refuses to hear them, tell it to the church. But if he refuses even to hear the church, let him be to you like a pagan and a tax collector.”

Wow, this was amazing from start to finish, but that last line alone is so powerful!

I’m am interested in the subject of family

Estrangement. I am a 67 year old father going through a painful process with my son. I would like to understand more. I don’t understand why this has happened.