"20,000 Years in Sing Sing"

Another successful find from my recent trip to Freebird Books has been an early edition of Lewis E. Lawes’ 1932 memoir, 20,000 Years in Sing Sing.1

I can’t get enough of that chummy, “let me give it to you straight, folks” style from autobiographies of the ‘twenties and ‘thirties. Those two decades are my favorite for both books and film, I think primarily because most writers at the time had either lived through the Victorian era or knew lots of people who did, and had a resulting “gee whiz, anything’s possible” perspective on human relationships, scientific progress, and criminal justice as a result. I will say that the copy I scored has unfortunately lost its dust jacket:

and it’s worth looking up other used versions to see if you can find one with the jacket still intact, because it’s a beaut.

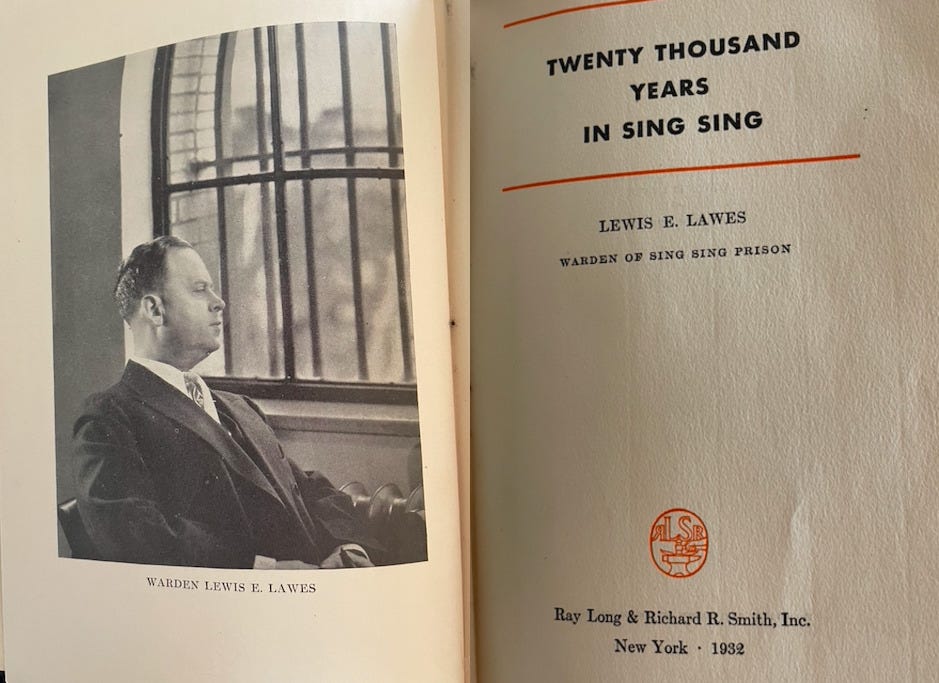

There’s a terrifically staged author photo and title page, too:

It’s snappy, often humane (though obviously from a top-down perspective) look at a really interesting transitional period in American prison reform after the decline of the Auburn model (rehabilitation through isolation and forced labor) and the introduction of psychiatric testing, Prohibition and subsequent “crime wave” sensational reporting, and increased emphasis on re-socializing the anti-social prisoner, recreation and team sports, and hygiene.

That being said, while it’s true that Lewes comes across as an unusually thoughtful and sympathetic warden of his era, he also seems to spend a lot of time tripping over rakes, like when he mistakes an owl for an attacking prisoner in his first year as prison guard:

My assignment was to the West Cell Block, where the third termers were confined. They were regarded as among the most dangerous prisoners. I gazed curiously at the sleeping forms, unable to believe that they were so utterly hopeless. I held a tight grip on my club and felt continuously for the gun at my side, prepared for any emergency. I had been well schooled in the use of arms in my three years in the Army, but the club — well, I didn’t know exactly what to do with it. Suddenly, as I passed along the tier, something banged me on the head. I almost died of fright. I gripped the club with both hands ready for service. For the moment I thought I was being attacked by one of those ruffians, who had somehow left his cell. I stood ready to protect myself as well as to inflict severe punishment on the offender. I felt rather foolish when I discovered that my assailant was only an owl that had flown in through an open window.

He later makes a remarkable discover that I can only describe as a “reverse Shawshank Redemption,” where someone very slowly brings a few grains of sand into the prison every day in order to eventually bash somebody over the head:

What we found [in Frenchy Menet’s cell] gave me my first impression of a prisoner’s ingenuity. Hidden in a corner were a number of keys, made to fit several doors of the institution. And in another corner we found a blackjack, a weapon made out of sand filled into a sock, an instrument that could be used with effectiveness…it was recalled that it was done during recreation periods while walking or drilling in the prison courtyard.

He had a way of stooping while walking. No one paid any attention to his stoop, and the occasional grains of sand which he picked up. But he saved every one of those particles. Took them in with him and deposited them in his sock. It took him a long time to fill that sock. He worked patiently until, on the night of his exhibition, he had a weapon that could, if given the opportunity, accomplish the desired purpose. Had any of us entered his cell alone that night, he would very likely have been clouted.

You also get the impression that security was not all it could have been in those days (emphasis mine; also, in a later chapter, Lawes mentions offhandedly that he’s pretty sure some of the prisoners were using his private car to sneak guns into Sing Sing for a few years).

Frenchy was an ingenious sort of fellow. When he arrived at Clinton Prison he was searched carefully. He was passed as O.K. Yet, all the while, he had six small saws concealed on his body. Only by a fortunate circumstance were they discovered. A few days after his parole in 1924, he called at the Dutchess County Jail to see a prisoner. His astuteness had not left him. On a hunch, he was stripped and searched. A saw was found concealed in the sole of his shoe.

The descriptions of various supervisors and prisoners he’s worked with over the years absolutely cannot be beat. “The man had one weakness: His daughters. His name doesn’t matter. Let’s call him Old Tommy Ahearn.” People just don’t talk enough like this anymore, and it’s a real shame.

He was hard boiled to the officers as well as to the prisoners. One didn’t dare just ask him for anything. “No,” was his favorite answer. He was a little fellow, weighed about 110 pounds, but mentally hard as nails. He had one weakness. His daughters. His name — it doesn’t really matter. Old Tommy Ahearn is near enough.

Again there’s the suggestion that security is not all it might have been, and a surprisingly casual reaction to nearly braining someone to death: “Ah well, good thing he pulled through! And of course, I learned a valuable lesson that day, which is that you should be very careful not to club victims of a knife attack, so really it’s all swings and roundabouts.”

I noticed, during one of my patrol rambles, a crowd of men who seemed anxious to screen something in their midst. It looked like a fist fight to me, and I made my way warily toward them. The men paid little attention to me; they were intent on what was going on. No one shouted. It was a silent, desperate battle — a test of brute strength. I knew my duty. I was pushing my way toward the combatants, when I saw a homemade knife raised aloft over the heads of the fighters. I didn’t hesitate a moment, lifted my club high and brought it down hard on the head of — the man who was being attacked. I struck the wrong man. The fellow who wielded the knife wasn’t touched. Luckily the stricken prisoner pulled through. But I learned something from the experience. I began to understand that in handling men one must have a discerning eye. The punishment cannot be indiscriminate.

Ah, times were simpler then.

[At Auburn] there was no analyzing of prisoners’ minds. They were either sane or definitely insane. For the insane there was the State Hospital for the Criminal Insane.

Speaking of great names, this one blows Old Tommy Ahearn right out of the water:

But there were things they didn’t see. They did not sense the spirit of Zebulon R. Brockway hovering over that institution.

Once again, security seems to be an afterthought in Warden Lewes’ approach to prison management. This reads like something Chief Wiggum would do:

About a year after I become the Superintendent, we were ready to move our entire population to New Hampton where the new Institution was to be built partly with prison labor. I shall never forget that trip to New Hampton. Five hundred and forty-seven boys and young men, all prisoners, tough lads from the East and West Sides of the great metropolis, accustomed to locks and keys and bars, were told to pack up their belongings and prepare for the journey. We had only our usual staff of officers, all unarmed and most of them newly appointed. The boys were in holiday mood as they boarded the City boat “Correction” that was to take them to the train in Jersey City…

All the boys had complete outfits and on the train there was one guard to every car — and he was unarmed. The route was through New Jersey. Had any of our prisoners escaped from the train we could not have taken them back legally. None of these prisoners had been convicted of a felony, and none, therefore, was subject to extradition. To get them back by force would have subjected us to a penalty, with a possible charge of kidnapping.

Later, once the reformatory has been successfully established in New Hampton, Lewes bumps into a few scouts from a little movie studio, who ask if they can film a wartime picture on his grounds. He not only agrees, but suggest they use his inmates to play both sides of the opposing armies. Once everyone has a horse and a gun of their own, he starts to reconsider the idea:

A holiday was declared. Nobody worked that day except the one hundred and fifty men picked for the film. The uniforms were distributed and in a little while one hundred men were assembled on the field resembling, in every detail, a unit of the United States Army. And in a few moments we heard the approach of a large company of horses, and fifty cavalrymen swept into view. Each one carried his regulation army rifle for the infantry and revolvers for the cavalrymen. Each was provided with blank shot.

I was proud of my men, but also somewhat nervous. None of us was armed. It was an open field, with absolutely no barrier between these prisoners and the outside world...There was no way that we could have restrained the boys had any of them taken it into their heads to run off the grounds and away.

There’s a lovely aside about a disgraced abortionist who has a cheerful, all-American perspective on communism: “Gee, it might not work out perfectly, but shouldn’t we give them a chance at least?”

There was the doctor. Ex-doctor, rather. For his name was marked off the roster. He had performed an illegal operation which had resulted in the death fo the patient. He was convicted of manslaughter and sent to Sing Sing. A man of fine education and a very clever fellow, about fifty, I should say…He was more than a radical. He was a Russian and a Bolshevist. An intellectual communist who adored his Lenin and sought every provocation to talk about him…

One could hardly resist listening to his discourse on Russia and the problems of Lenin’s government. He never criticised America, nor the capitalist system.

“It’s an experiment, Warden,” he would say. “A lesson in self-control. Can the proletariat measure up to it? Time will tell. It may be all wrong but it’s worth a try.”

Doc left us some years ago. It is rumored that he now holds a responsible and confidential position with the Russian Government. Rumor has it also that he has amassed another fortune. Possibly he still wears flannels and the attire of the “common people” which he so steadfastly adhered to in Sing Sing.

Then there’s a brief encounter with then-Governor Al Smith that you can just feel taking place in a Coen brothers movie, likely with John Goodman in the role:

At the table before me sat the Governor, in shirt sleeves, his striped suspenders loudly proclaiming the informality of the man. As I entered he was biting into an ear of corn with all the vigor of his indomitable personality. After a word of greeting, he resumed his munching. “What’s up, Warden?” he asked, between bites. “I thought you could run that place. Are the boys too much for you? Pulling your leg, so to speak?”

I told him the story and reminded him of his promise to let me run the prison in my own way. “If that is not to be continued, you can have my resignation at once.” He was at his second ear of corn when I had finished. I remember to this day how he slowly buttered it, salted and peppered it thoroughly. Then he looked up at me and said, “Now, Warden, you go back and tell that crowd that you’re to run that prison as I said you should. Without any interference.”

Some absolutely god-awful legal advice:

Any prisoner of average intelligence can defend himself in court without the aid of counsel. Most prisoners are familiar with criminal court rules. Points of law, recent decisions and court procedure are always important topics for discussion in the prison courtyard.

“The beans did the trick.”

Now, prison fare is not, or rather in those days was not all that could be desired. Prisoners, however, do not often complain about food unless it is utterly unpalatable. The day the condemned woman came in the menu was porks and beans. Beans are beans at all times. All housewives know that sometimes they are overdone, often underdone. Prisoners were accustomed to both kinds of cooking. They seldom complained. If the men were hungry, the beans disappeared regardless of their quality. If the prisoners were not particularly famished, the beans were left over and that was all there was to it. But that day the men were under a nervous tension. A woman in the death house! And all because a man talked too freely. Their peculiar sense of chivalry was touched. It did not need much. The beans did the trick. As luck would have it, the beans were overdone and hard as marbles. The men not only refused to eat them, but commented freely in protest.

An early precursor to the popular sentiment “it’s never the people you wish were polyamorous who turn out to be polyamorous”:

He was a newly admitted prisoner convicted of bigamy. He had married, not wisely, but often. Four trusting damsels he had led to the altar on as many occasions. How he had managed to keep the secret will ever remain a mystery. Finally, however, our Don Juan met his doom. One of the ladies discovered his quadrumus life, and after a few vexatious months he found relief, and a haven, within the walls of Sing Sing.

Now, this man might have had some peculiar love charm. A Don Juan par excellence. But he was far from an Adonis. It hardly ever fails. The bigamist is seldom the strong, handsome fellow; more often he is the frail, weazened shrimp of a creature who wears a size 13½ collar. The kind women like to lord it over.

Once again, security is just bottom of the list of priorities at Sing Sing:

Back at the prison I summoned the guards. They were prepared; but one of them was honest enough to confess that while working with a road gang he had lost his gun. When a policeman in any city loses his gun it’s a trivial matter. When a guard in charge of convicts loses his gun — there is an immediate threat.

The book closes with an explanation of his position on capital punishment (he’s against it, but not for any sissy reasons like sanctity of life):

Neither the threat of death, nor its infliction, has ever halted the march of moral progress. Nor has the fear of death been able to impress a new order of living for which the people were not prepared by education and culture…

Dr. Frederick L. Hoffman, the statistician and consistent opponent of capital punishment, struck the same note in a letter to me in which he asks: “What would be the attitude of the American people if by good or ill circumstances the ten thousand men and women who in any one year commit our murders and manslaughters in these United States, would all be convicted of murder, sentenced to death and that punishment actually inflicted?” What indeed, but an almost universal cry for abolition?

From every point of view, therefore, the death penalty is futile. Its wide and frequent application would arouse public fury against it; the practice prevailing in many jurisdictions to avoid it and the refusal of juries to convict in the face of undisputed evidence of crime, is reflected in the general disrespect of all law and procedure, and is an undoubted influence for crime.

My opposition to the death penalty is not based on sentiment or sympathy. I am not altogether impressed with the religious enthusiasts who talk about the sacredness of life…I am opposed to the death penalty because the evasions, the inequality of its application, the halo with which it surrounds every convicted murderer, the theatrics which are so important to every court proceeding where the stake is life or death, the momentary hysteria, passion and prejudice aroused by the crime which often make it impossible to weigh the facts carefully and impersonally and, finally, the infrequency of its application — all tend to weaken our entire structure of social control.

And (unfortunately not presciently) a call for fewer prisons in the future:

Attacking the problem of crime and criminals through prisons is to approach the problem hind-end foremost. The answer does not lie in “more and larger and safer prisons.” It is rather in ascertaining some method of diminishing prison populations; of reducing them without danger to the peace and security of the public; of turning these prisons into plants where human impulses and the desire for normal living can be recharged with vigor and encouragement.

It’s worth a read if you can find a copy! You might also try Life in Sing Sing, by Number 1500 (sentenced in 1897), and republished by HVA Press, for a prisoner’s perspective of the same institution.

Allegedly there’s some connection with the Spencer Tracy/Bette Davis movie of the same name, but beyond the title and the setting I can’t say I see it. The book’s a pretty straightforward memoir of Lawes’ time as warden at Sing Sing, with a few early chapters dedicated to his earlier career as guard and reformatory superintendent, while the movie’s about a convict named Tommy Connors (Tracy) who’s both guilty and sort of the victim of an unfair system, then takes the rap for his girlfriend shooting someone else and goes bravely to the chair. Nothing like that happens in the book, so don’t say I didn’t warn you.

After all the wonderful stuff in this post, the thing that stuck with me was, “Who puts PEPPER on corn on the cob?”

Saw Guy consumes my waking thoughts. 6 (?!) small saws? How small exactly? Where were they? WHAT was the "fortunate circumstance" that led to their discovery? How many times do we think he WASN'T caught smuggling small saws?