A Good Day To Join The Hittite Army, Chapter Six: A Case-By-Katabasis Basis

A Good Day to Join the Hittite Army, Chapter One. Chapter Two. Chapter Three. Chapter Four. Chapter Five.

Back at home — I mean my home, that is; I’m sorry but I haven’t the faintest idea where you live, although I’m sure it’s very nice and you’ll have to tell me all about it some other day when we’ve got the time — there’s a fellow named Ninurta, or at least there was a fellow named Ninurta when I was there last. For years he had claimed to have visited the Underworld the night he turned twelve as a sort of birthday-present from his father, who Ninurta claimed was Ninazu, the dread god and king of snakes.

I am sorry to say that we none of us believed him. Ninurta was the sort of boy whose claims one was always inclined to take under further review, if you know what I mean. If Ninurta told me it was raining, I would not have gone so far as to contradict him, but I would have stepped outside to see for myself if I got wet. He also said that Inanna had been his wet-nurse, that his mother’s little red cow that was tied up in the back of their garden was the great Bull of Heaven, and that he had been chosen as a very small boy to serve as the image-model for “Virtue” on a famous set of cylinder seals in Babylon. We tried not to take him too seriously, is what I mean. Some of the other children occasionally attempted to help cure him of this habit by giving him a beating, in a desultory and comradely sort of way, but it never seemed to dull his interest. He might temporarily abandon whatever story was causing him problems in the moment, but next morning you’d find him down at the village well, claiming to have just spoken to a scarab beetle piloting the barge of the sun, and you’d just have to beat him again.

Even if Ninurta had been the son of Ninazu, dread lord of the Underworld and king of snakes, I very much doubt Ninazu would have taken him anywhere, as a birthday-present or for any other reason. He was that sort of a boy. I would not go so far as to say that his mother exposed him as an infant on a wild hilltop in the hopes that the gods would take him, but let us say that his mother was not scrupulously exact about his whereabouts on more than one hilltop, on more than one occasion, all throughout his infancy and even well into early manhood. He always turned up again.

I’ll say that much for him: There was simply no discouraging Ninurta. When he claimed to have visited the Underworld, we used to tease him by asking him questions about the nature of his voyage, how much he had had to pay the ferryman to cross the river of souls, what he ate while he traveled there, and so on. But there was no daunting him!

“Oh, my father Ninazu gave me two gold coins to pay my fare! He has wealth beyond imagining, and it is colder than cold, for it lives in the deepest parts of the black earth.”

“Oh, I was given grapes and dates and almonds to eat when I was hungry, for I traveled with my little red cow (which you know is in truth the Great Bull of Heaven), and whenever I was hungry I would tap on his leftmost horn, and food would pour out, and when I was thirsty I would tap on his rightmost horn, and the most wonderful sasqu-drink came pouring out, and I drank.”

“When the passage become too difficult, then my father the dread king Ninazu clapped his mighty hands together, and the seven Anunnaki appeared in glory and power, and they carried me across. Later the beautiful queen Ereshkigal showed me the gardens of the night with her own hands, and made me a special little chair out of red coral, to sit and look at the gardens whenever I liked.”

Of course he may have been making it all up. But if Ninurta had been to the Underworld — and after all he may have been! The son of a god and a woman can tell lies just as easily as the son of a man and a woman, I expect, and even a broken sundial can tell you whether the sun is out or not — he must have been to a different Underworld, with a different class of the dead, than the one I saw. Or perhaps he got the special tour that is reserved for demigods and champions and heroes, and I got the short end of the ox-horn.

Certainly there were no gardens that I could see, only a lot of rather wan-looking people milling about. I think I have mentioned that my own mother was there, which had rather surprised me, since I had only a few months ago left her living. I am a dutiful son, and my travels have not stripped me of my manners; I greeted her first, although I spotted several other acquaintances of mine in the crowd and hoped to speak to them, too.

“Hello, Mother,” I said. “You’re looking well. I speak generally, of course,” I added, once I realized how that could have come across, “rather than of details. Given the circumstances, which both shock and grieve me exceedingly, you are looking surprisingly well, I ought to have said.”

She made as if to kiss both my checks (although of course she couldn’t have done so), and I felt a sort of begrudging idea of a pucker drift from one side of my face to the other, before she motioned that I should sit down on a little stone bench beside her, slightly apart from the others.

“I hope you don’t mind my asking, Mother,” I said after a moment (for she did not seem disposed to say hello beyond the air kisses), “what you’re doing here, and whether you feel that you need to be avenged, or anything like that, or if there’s anything you’ve left unfinished in the upper world that I could, well, finish for you. Or anything like that.”

“If you happened to have a little sheep with you,” my mother said, “you could slit its throat, and pour its blood over the sand — or if you had a little barley with you,” she said, for she must have realized by the look on my face that I had no sheep with me at all, “you could set it on fire in a little brazier and I could eat the smoke that rose from the ashes. But I can see by your face that you have no barley with you, and those are the only things I can eat down here.”

“Oh,” I said, and then after a minute, “Well, I’m sure it’s quite tasty when you get used to it, smoke and blood.”

“It isn’t,” she said flatly. “When you’re here, you’ll hate it.”

“Ah,” I said, because I couldn’t think of anything else to say.

“My son, the reason you see me here, wrenched from the light of the sun so cruelly before my time,” she said, “is because not three days after you left our village in search of the Hittite army — may their pillows be filled with dung-beetles and poisonous adders, may they get no rest, may fleas and hoof-rot do away with their cattle! — the Hittite army came back to town, and as this time we had no barley left to give them, set fire to most of the houses and used all those who could not flee into the hills as target-practice before riding on.”

“Oh, I say,” I couldn’t help exclaiming, “that is bad luck. Imagine my missing them by only three days.”

Which, you might expect, my mother did not very much like. Fortunately at just that moment the ground cracked in front of us, and everyone in the little antechamber began to slip downwards into the great blackness that had opened up just beneath our feet. “Here comes Hell and all the powers therein!” a terrible grating sort of voice bellowed, and then we were falling again, my mother and me and all the other dead people — and wouldn’t you know it, but there was Ninurta falling right next to me, so I suppose in the end that story about his trip to the Underworld had been true after all.

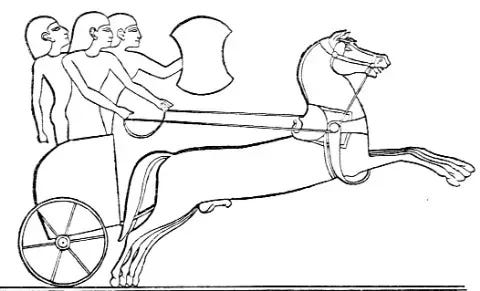

[Image via]

Ninurta was the original Gerber Baby, don't you know.

Beyond anything I could hope or dream for in terms of reading material on a Tuesday lunch break in the end days of late capitalism. Thank you!