The Best Read of the Summer is Edna Ferber's 1933 Story Collection, "They Brought Their Women"

and it's not even close

There’s a terrific used bookstore near us in Michigan, and last week I managed to pick up a copy of Edna Ferber’s short story collection, They Brought Their Women, almost entirely on the strength of the title. Decisive and arresting, no?

I was vaguely familiar with Ferber as the author of Giant and Show Boat and Dinner at Eight, and might even have dimly associated her with the Algonquin Round Table, but that was about it. She’s hardly forgotten today – just a few years ago Harper Collins reprinted three of her novels, So Big, Giant, and Saratoga Trunk — but there’s been a steep drop-off in popularity, going from one of the most successful authors of the mid-20th century to “Oh, that name sounds familiar.”

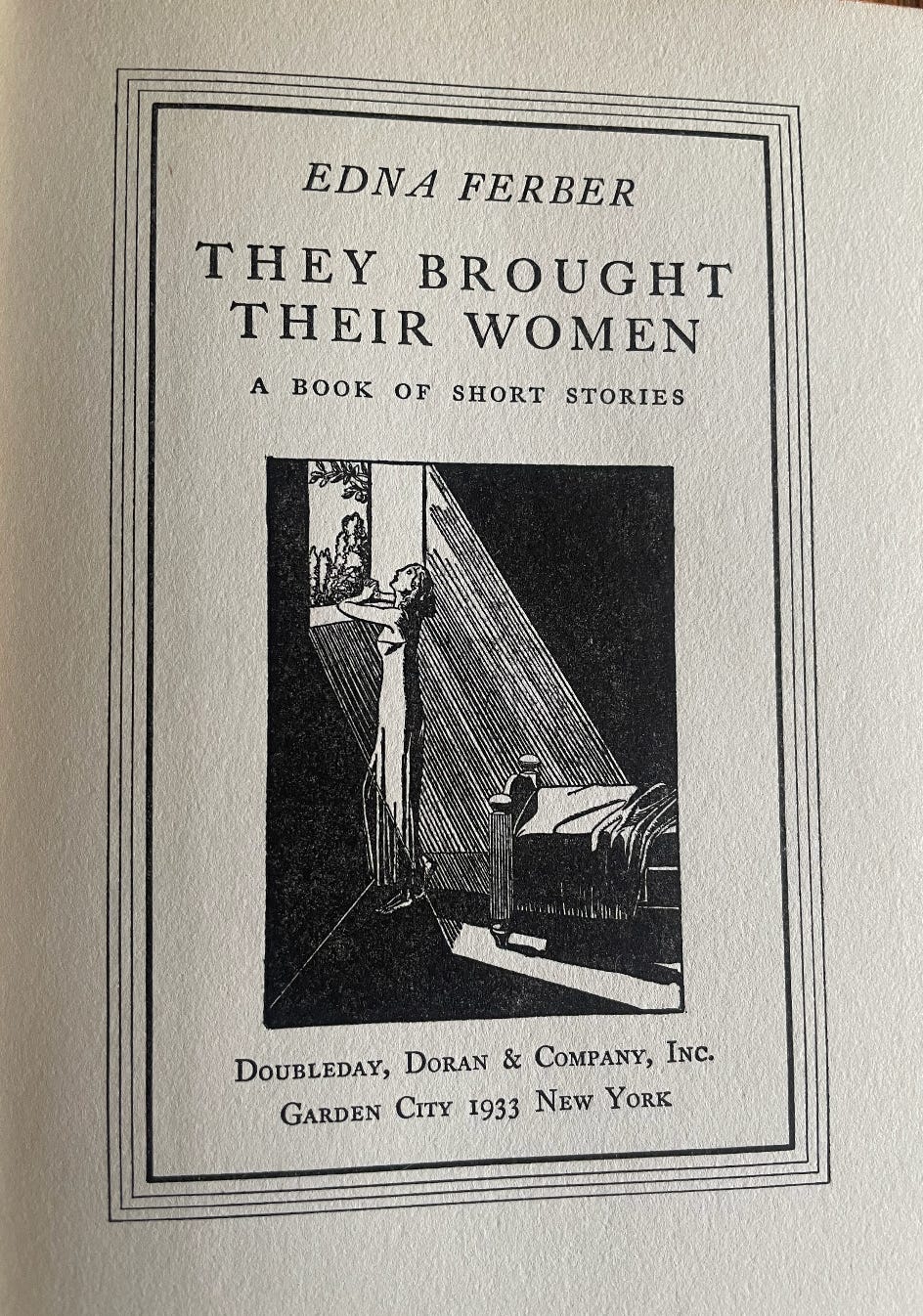

They Brought Their Women is such a good read; I can’t recommend it highly enough. The titles and illustrations alone are worth the price of the book — “Hey! Taxi!” and “Wall Street—’28” are particularly delightful — but the stories themselves are chatty, direct, engaging, measured, funny, and confidently written. The 30s-era dialogue and details are charming but that’s not to say it’s only valuable as a period piece.

The book opens with a tribute to the apparently-vanishing art of short-order pancakes (I cannot remember the last time I was more swiftly, immediately, and thoroughly won over by the first page of a book):

“He is vanishing—that exquisite craftsman who, in white cap and apron, used to ply his trade for all to see and admire through the plate-glass window of the chain restaurant. With what grace he poured the creamy batter, with what dexterity he jerked back the wide-lipped pitcher; what a sense of timing in the flip of the wrist that turned the bubbled surface to reveal the golden-brown underside of the hot pancake. Perhaps tact has all but banished him, or fear or caution. Certainly the hungry man in the street in this Year of Grace must have felt keener resentment, known deeper frustration, as he watched the delicate circlets browning for the delectation of other mouths…

The American short story of a passing generation was the hot pancake of literature. The same deft pouring of the batter, the same expert jerk, the same neat flip of the wrist at the end.”

The bibliography has convinced me to become a Ferber completist. More books ought to be called things like Buttered Side Down and Roast Beef Medium and CHEERFUL—By Request. I don’t know what I’ve been doing, calling my books other things; from now on I shall reform.

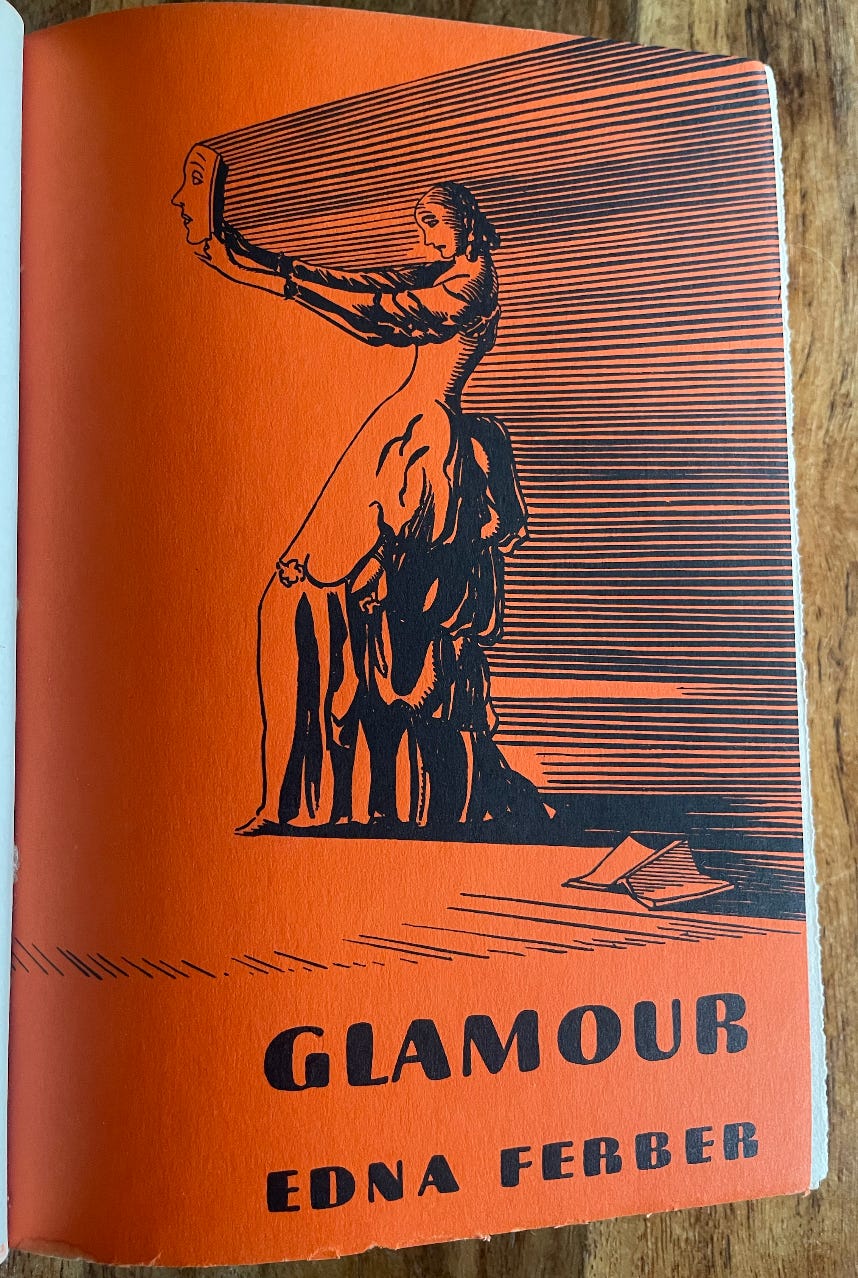

The first entry, “Glamour,” is perhaps my favorite (and get a load of the chapter header illustration! It’s gorgeous). It follows a day in the life of a busy stage actress about to close in one play and open in another.

Ferber, incidentally, is a big fan of the old “She was not a beautiful woman…[Describes a very beautiful woman] method, and does it about as deftly and generously as anybody can.]” She eats, she works, she quarrels lightly with her mother, she sees her child, she has her hair done, she changes into “brown kid pumps, step-in, slim wool dress,” she works. And what she eats!

“It’s going to be a fierce day for you,” said Miss Grassie. “Mutton barley broth, very hot, Walker. Lamb chops, creamed celery, chopped fresh pineapple. That’s nourishing, but light.”

“This settled, they ate scrambled eggs and hot cocoa, and Nesbitt mixed himself a highball. One o’clock. Two o’clock.”

Hey! Taxi! is of course another all-timer. These illustrations make me nearly sick. I want illustrations like this in every book from now on.

This story follows Ernie Stewig, a Manhattan cab driver who loves his wife but thinks kissing her goodbye in the morning would be queer, even “offensive”:

The minute-by-minute descriptions of his day are wonderful:

“Up and down, up and down, putting a feverish city to bed. Like a racked and restless patient who tosses and turns and moans and whimpers, the town made all sorts of notional demands before finally it composed its hot limbs to fitful sleep.

Light! cried the patient. Light!

All right, said Ernie. And made for Broadway at Times Square.

I want a drink! I want a drink!

Sure, said Ernie. And stopped at a basement door with a little slit in it and an eye on the other side of the slit.

I want something to eat!

Right, said Ernie. And drove to a place whose doors never close and whose windows are plethoric with roast turkeys, jumbo olives, cheeses, and sugared hams.

It’s hot! It’s hot! I want to cool off before I go to sleep!

Ernie trundled his patient through the dim aisles of Central Park and up past the midnight velvet of Riverside Drive.”

Also wonderful is “Fräulein, another “brisk day in the busy life of a working woman” story, this time about a German nanny named Bertha working for an American couple (most, but not all of these stories are set in New York) who sees her boyfriend Otto on her one afternoon off a week.

The boyfriend gets one of the best lines in the book:

“Her clothes! You don’t need her clothes!” cried Otto, full of class hatred and beer.

Although it’s a close competition between that and the description of the nanny’s employer, Carlton Schurtz’ sudden decision to propose to his wife several years before the action of the story:

“An emerald,” he resolved, his gaze resting a moment on her ringless left hand against a black coat sleeve. “Square-cut, the size of a Bronx-express headlight. Black velvet by Worth. Gray crêpe, with handmade collar and cuff things, by Molyneaux. Dull green tea gowns. Schiaparelli sports things to watch me drive off from the first tee. One whole closet for shoes and another for hats. Stockings you can stuff into a thimble.”

For he, with his millions, had been around by the time he was fifty-one.

The couple’s two children are introduced in a beautiful little logic puzzle of a sentence:

“If Camilla, now aged three, had been a boy, there would have been no Camilla. Carlton Schurtz, in his mid-fifties, must have male issue to prove his virility and satisfy the egotism of an old bachelor who has married a young wife. Like a last amazing floral set-piece of fireworks terminating an evening of conventional skyrockets and Roman candles, Carlton Schurtz III was produced to the accompaniment of rapturous oh’s and ah’s. Then darkness. The entertainment was ended. Camilla, three. Carlton III, eighteen months.”

Bertha and Otto also attend, at one point, a lightly-fictionalized and heavily-satirized Nazi rally (Ferber was Jewish and would, five years later, initially dedicate A Peculiar Treasure to “Adolf Hitler, who has made me a better Jew and a more understanding human being, as he has of millions of other Jews, this book is dedicated in loathing in contempt,” although by the time the book reached publication, was replaced by a dedication to her family.

Then there’s Wall Street—’28.

A few of these stories fall into the delightful category of “inspecting a good-but-not-great marriage,” which is neither dull nor depressing, but beautifully and poignantly realistic about the differences between two people who are pretty well suited to one another, and reasonably attentive to the other’s differences, but who nevertheless misunderstand one another in pretty substantial ways.

“Certainly Hilda Condon could pride herself on the gift of making a man comfortable. A perfectly managed household. Fresh bed linen daily. Cass’ soap dish was never gelatinous. Hilda never said who was that on the phone, dear. There was his room; there was her room; a dressing room between.”

The last story in the collection, “Keep It Holy,” runs a close second to “Glamour” for me, and similarly follows a single day in the life of a busy woman living in Manhattan, this time a recent arrival from a farm in Connecticut, Linny Mashek, who works for minimum wage at a milliner’s.

“Miss Kitchell, Millinery, Hats Made On The Head, sold guaranteed copies of French models at five to seven dollars…This just came in…You can’t tell a thing in the hand…I love it on you…More over the eye…It’s a little Suzanne Talbot1…It’s a little Rose Descat2…It’s a little Reboux3…This just came in…I love it on you…More over the eye…You can’t tell a thing in…In the littered workroom behind the showroom Linny Mashek stitched and folded and steamed and pressed and cut. It’s promised for tonight it’s promised for tonight it’s promised for tonight.”

“Sundays were the worst. There were the evenings during the week, of course, but they weren’t so terrible. An evening comes to an end. By the time she had eaten her dinner and read the tabloid and perhaps gone to a movie it was ten or after. There were always Things To Do, evenings; stockings to mend, gloves to wash, a dress to press, a letter to write, hair to shampoo, nails to manicure. Then, too, you are tired and sleepy after stitching hats all day, and trying them on customers’ heads, and rushing them through for delivery. But Sunday! Sundays stretched endless hours ahead. You got nowhere. They were like a bad dream in which you walk and walk and make no progress.”

I’ll read almost anything that describes a single, interesting, sometimes-melancholy day in the life of a working girl. Bonus points if it describes her meals in detail. I will never get tired of this kind of thing, not if I live to be 300:

“Linny almost always ate her dinner at Werner’s cafeteria. It was cheap, bright, good, clean. You got your tray, you selected your food, you served yourself. A long counter stretched the length of the farthest room. On it was ranged a bewildering variety of food. To choose amongst it was to illustrate the impressive power of decision in the human mind. Enormous roasts of beef and of pork and of lamb; pans of fish; mounds of vegetables, green, white, gold; bowls of salad; quarter sections of fruit tarts, mosaics of plum and apple and apricot; acres of coffee cake. The catch in it was that, the decision once made, the soup was found to taste strangely like the roast, and the roast like the vegetables, and the vegetables like nothing at all. Still, it was almost hot; and nourishing.”

“A movie. I’m sick of movies, she said to herself. Good and sick and tired of movies. Always the same thing. All that necking. And the couples around holding hands, too, and carrying on. It was always too hot in the movies.”

I know what you mean, Linny! I know just what you mean!

You can find used copies of They Brought Their Women online that are reasonably cheap: Bookfever has a first edition for fifteen dollars, Biblio has multiple copies between seven and twenty dollars, and it shows up fairly often on Ebay, too. That said, if Harper wants to reissue They Brought Their Women someday, and they want someone to write a preface, I’m only a phone call away…

Fresh bed linen daily?!

This is so great, Daniel Lavery.