Interlude: The Problem With The Boxcar Children Is They Never Got To Spend Enough Time In The Boxcar

For the ongoing Boxcar Children series, start here. Parts II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII. Consider this an interlude of sorts in the slowest-possible-moving reimagining of the first Boxcar Children book.

The boxcar in The Boxcar Children carries a disproportionate weight throughout the series.1 The “Boxcar Children,” Henry, Jessie, Violet, and Benny, only live in the boxcar in the first book; they never live there again. There are more than 200 official Boxcar Children novels, and in all but one of their adventures, there is no boxcar. The children find the car in the middle of a freak thunderstorm after fleeing the twin specters of the workhouse and the orphanage:

Faintly outlined among the trees, Jess saw an old freight or box car. Her first thought was one of fear; her second, hope for shelter. As she thought of shelter, her feet moved, and she stumbled toward it.

It really was a freight car. She felt of it. It stood on rusty broken rails which were nearly covered with dead leaves…

Violet passed the hay up to her brother, and crawled in herself. Then Jess handed Benny up like a package of groceries and, taking one last look at the angry sky and waving trees, she climbed in after him.

The two children managed to roll the door back so that the crack was completely closed before the storm broke. But at that very instant it broke with a vengeance. It seemed to the children that the sky would split, so sharp were the cracks of thunder. But not a drop of rain reached them in their roomy retreat. They could see nothing at all, for the freight car was tightly made, and all outside was nearly as black as night.

I couldn’t tell you any of the mysteries the Boxcar Children would go on to solve in the many sequels, although I remember reading more than several. But I could tell you anything you wanted to know about the special pink cup that Benny found in the dump, how Jessie stored the milk bottles in the little river behind the boxcar to keep them cool overnight, how they washed their clothes and cleaned the big iron kettle they cooked their dinners in, how often Henry brought home cheese in waxed paper from his job and where they all made their beds in the car.

They should have stayed in the boxcar forever. They ought to have spent the rest of their lives roaming from town to town across America and helping other desperate children reclaim old rolling stock on spur tracks in former logging camps. There are plenty of books about children who live in houses with their families; there are precious few books about children who live in abandoned freight cars, and Gertrude Chandler Warner, who I’m sure was otherwise a decent and upstanding person in her private life, did her readers a real disservice by hustling the children out of the woods and into their grandfather’s house prematurely.

They should have lived in the train for a thousand years. Or if they had to leave the boxcar, they should have made an equal trade, rather than forfeit their beautiful chores-based mutual independence for the sake of re-inheritance. If they had to have fled the boxcar, let them stay squatters; give them next an abandoned factory, an empty miner’s cottage, a dry cave on a river-island, a ghost town, an unused hunting blind – The Boxcar Children Go Further Underground, The Boxcar Children Flourish Outside, The Boxcar Children Climb A Tree.

Can you imagine the dishwashing when the gay party returned to the freight car? Children do not usually care for dishwashing. But never did a little boy hand dishes to his sister so carefully as Benny did. On their hands and knees beside the clear, cool little "washtub," the three children soaped and rinsed and dried their precious store of dishes. Jess scoured the rust from the spoons with sand.

The Boxcar Children, the first one at least, balances right on the edge of small-c conservative, Protestant work ethic home-ec enthusiasm (they’re very excited to do chores, these children) and DIY punk collectivism (they’re doing chores while running from the state, the cops, and the family), although everyone knows the children end up restored to all three by the end.

Children, especially siblings, often play at running little proto-businesses together; some of my earliest memories of community organizing came from trying to run a baked goods stand with my brother and sister in the summer. My sister, like all eldest children, was a parasitic landlord; she stayed indoors where the A/C was running “supervising” the baking of the cookies (in actuality eating cookie dough for free) while my brother and I manned the stand. But there was something beautiful, even utopian, in our constant squabbling and jockeying for position; like all young children we were fanatically obsessed with “fairness” and would rather have drank poison than allowed either of the others to get even an inch more than their fair share of anything, and it was wonderful to be turned loose upon one another, fighting madly and gleefully in our own weight class without the heavy hand of adult interference from parents or teachers.

I have not spoken to either of my siblings since 2019 and I do not believe I ever will again. We have accumulated all of the memories we will ever make together. Although they are very much alive, they are not “in living memory” with me, nor I with them; to me they exist only as a mental archive. We used to do a lot of chores together, we used to take turns practicing twenty minutes at the piano on weekday afternoons, together we jostled and schemed for power in the court of childhood; the kingship is dissolved, the court is in exile. The end of any childhood is a bit like the French Revolution; things that mattered a great deal at eight years old seem in retrospect like having been the First Valet de Chambre at Versailles in the Ancien Régime. You have to understand, it seemed terribly important at the time.

Eventually the children learn that the grandfather they feared is both richer and kinder than they had been led to believe, and The boxcar is hideously returned to them once they’ve been successfully re-adopted back into their own family, but what was once a home has been transformed into property, and worse than property, a novelty:

Would you ever dream that four children could be homesick in such a beautiful house as Mr. Cordyce's? Jess was the first one to long for the old freight car….

[Mr. Cordyce] led the merry little procession out through his many gardens, past the rose garden, through the banks of purple asters. Then they came to an Italian garden with a fountain in the middle, and a shady little wood around the edge. Among the trees was the surprise. It was the old freight car! The children rushed over to it with cries of delight, pushed back the dear old door, and scrambled in. Everything was in place. Here was Benny's pink cup, and here was his bed. Here was the old knife which had cut butter and bread, and vegetables, and firewood, and string, and here were the letters for Benny's primer. Here was the big kettle and the tablecloth. And hanging on a near-by tree was the old dinner bell. Benny rang the bell over and over again, and Watch rolled on the floor and barked himself hoarse.

The children were never homesick after that. To be sure, a dull and ugly freight car looked a little strange in a beautiful Italian garden. But it was never dull or ugly to the Cordyce children or their dog. They never were so happy as when showing visitors each beauty of their beloved old home. And there were many visitors. Some of them were fascinated by the stories of the wonderful dishes and the shelf. And the children never grew tired of telling them over and over again.

The Boxcar Children themselves, importantly, tell the story of the boxcar over and over again, because the boxcar is the last real thing that happened to them. The boxcar was a house; now it is a parody of a house. The Boxcar Children do not tell visitors the story of The Yellow House Mystery or Surprise Island because these are not real things; only the boxcar was real. When they left it for their grandfather’s house, they were as thoroughly barred from ever truly returning as Adam and Eve were barred from Eden by the cherubim with the flaming sword.

They cannot go back to it even now, with the boxcar sitting in their grandfather’s “beautiful Italian garden”; this is why they compulsively repeat the story to anyone who looks at it, as the widow’s daughters in Perrault’s Diamonds and Toads cannot help but disgorge jewels or vipers from their mouths whenever they speak. They reenact, they obsess, they re-create, they repeat, but they cannot go back. They can show a visitor the pink cup, but they cannot use the pink cup again; it has been disenchanted by the grandfather’s well-furnished kitchens, and is once more a piece of trash fished out of the dump. Here is the kettle, but now there is no longer any need for the kettle; here is the boxcar but where is the forest that made life in the boxcar possible, with blueberry bushes and a stream to keep milk cold in? A beautiful Italian garden is not a forest; it is a visual joke about a forest.

The Boxcar Children “were never so happy as when showing visitors each beauty of their beloved old home,” but their new home has eaten the old one, and it has eaten their happiness with it. All they can do is point at what they have lost and say Someone used to live here. Something used to happen here. You have to understand, it seemed terribly important at the time.

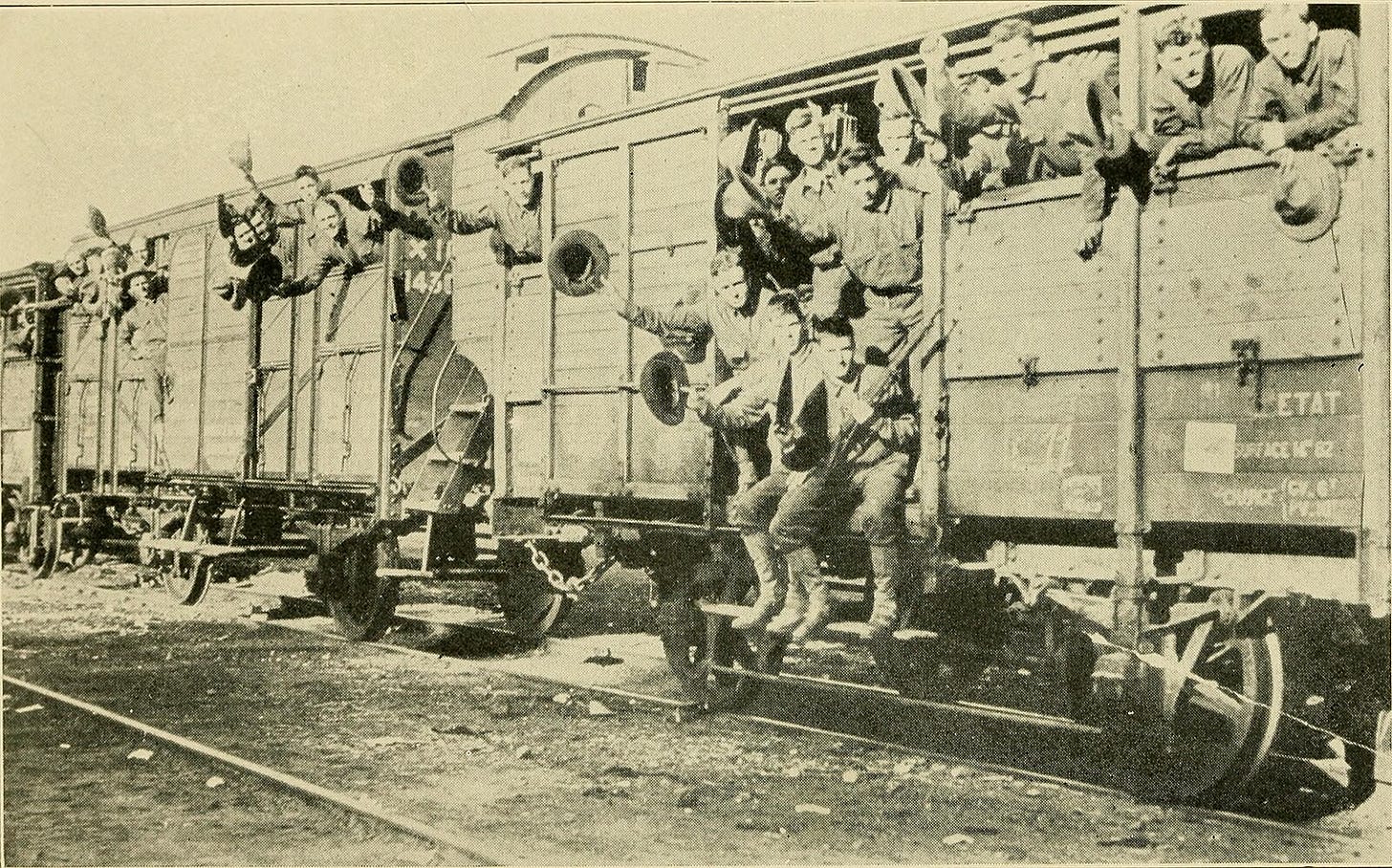

[Image via Wikimedia Commons]

We’re coming up on 100 years of boxcar children, incidentally; the first book was published in 1924. The original author, Gertrude Chandler Warner, wrote the first nineteen titles in the series; the 183 other titles (including prequels, specials, interactive mysteries, and cryptid adventures) were written by a team of ghostwriters.

You get me. I wanted Jamie and Claudia to live in the museum forever (with their wax paper covered sandwiches of course) I wanted the Boxcar Children to stay in the boxcar

This is the deep analysis of TBC that my soul has always craved. Thank you , Danny.