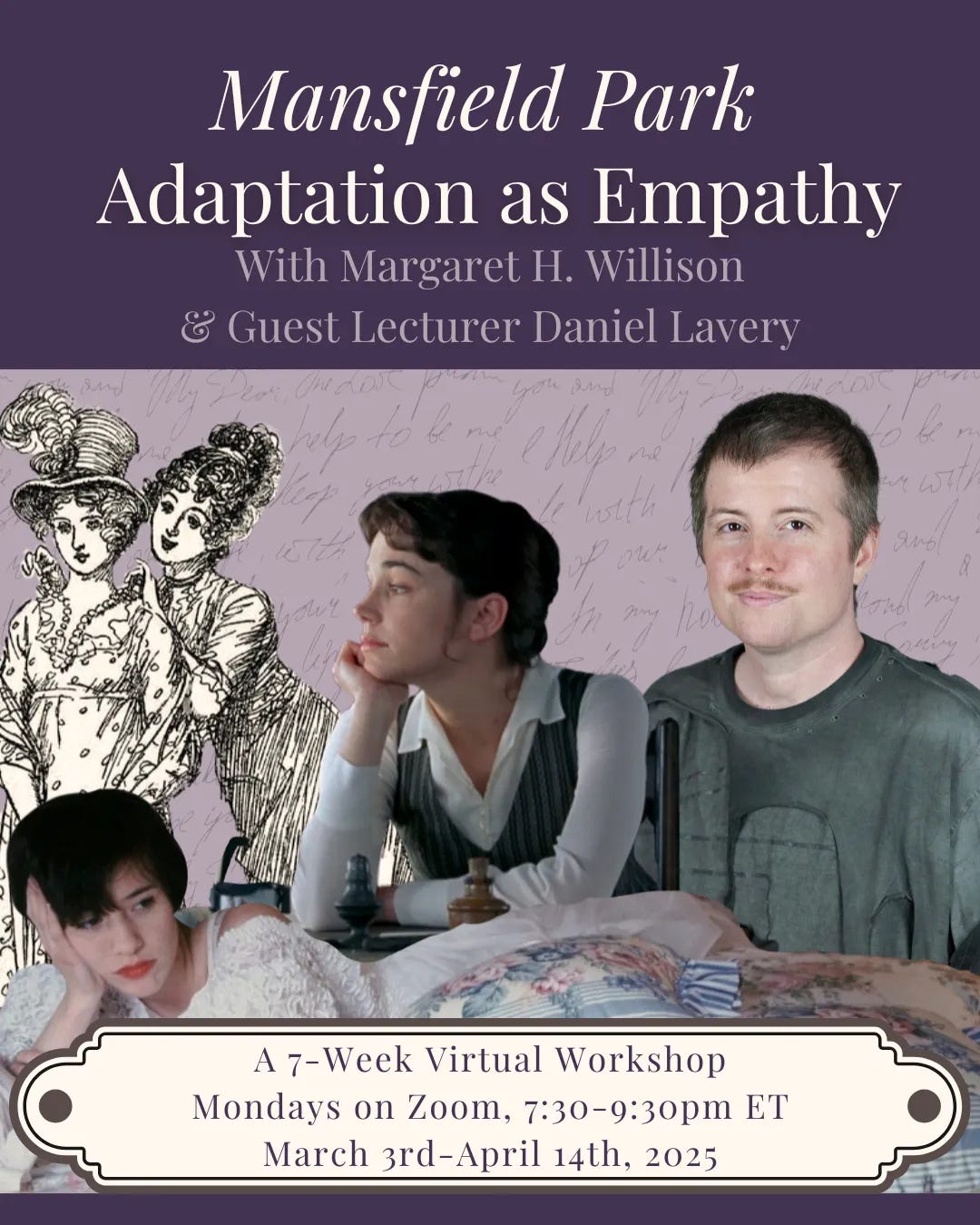

Join Me In Talking About "Mansfield Park" and Marrying Jiminy Cricket With Margaret Willison on March 24th

“The reason so many people like Emma is because it’s a really fun book about a thoughtless woman who marries her conscience, like if Pinocchio married Jiminy Cricket. The reason so many people get mad at Mansfield Park is because Fanny marrying Edmund is like if Jiminy Cricket married his own Jiminy Cricket.”

I’m very excited to join my friend Margaret Willison later this month during her course on Mansfield Park and empathy. I’ll be there to mount a defense of Edmund Bertram that’s only 25% tongue in cheek. I don’t think you’ll walk away newly in love with him, but I do hope and believe you might find him slightly more interesting, funny, and worthy of attention afterwards.

If you’re interested in that sort of thing, you can sign up for the class (or request a scholarship if the cost is prohibitive) here. You can also sign up for Margaret’s newsletter for free here, and I highly recommend that you do.

“Guest lecturer” really makes it sound more formal than it is; I’ll just be joining her for a conversation during the March 24th session, although you can be sure I’ll try to invite myself to further classes.

In honor of the occasion, I’ve released Texts From Mansfield Park from behind a paywall, so you can read it here.

FANNY: ₕₑₗₗₒ

MARIA BERTRAM [disgusted]: I’m thirteen

what are you, ten

You can also read my conversation with Margaret about Edmund and my affection for him and this strange, thick novel here.

Here’s a snippet of our conversation in case you don’t feel like clicking:

I like Edmund for a few reasons. I like that he's at odds with himself, often without realizing it, and that we get to see him try to lie to himself while having a constitutionally honest personality, and how difficult that makes things for him. I like how he's always trying to put a bright spin on hopeless things. He's a little bit of a Stepford Wife in that way. Fanny has this sort of mystical inward journey, her own dark night of the soul, but her story is fundamentally about having the courage to stick to her convictions, and to continue to love the same person she's loved the whole time.

Edmund's story is that he sort of inadvertently places a curse on himself: About a third of the way through the book, he tells Fanny that "it often happens that a man, before he has quite made up his own mind, will distinguish the sister or intimate friend of the woman he is really thinking of more than the woman herself." He's saying this about Henry Crawford and the Bertram sisters, and is perfectly wrong, of course, but it's entirely true about himself, and he goes on to suffer for another 200-some-odd pages as a result of it. He's rerouted away from real human connection by charm, which is such an interesting and, I'm sorry to use the word here but relatable problem, and he's often very funny in an agonizing way.

I suppose I want to defend him most of all because the Henry Crawford charm offensive always, always works on me. Every time I reread Mansfield Park, by the time Fanny hears him reading Shakespeare, I've joined the side of Sir Thomas and everyone else, who want to override her taste, her judgment, her inclination, her values, and say, "Just like him, the way that we like him, and all of your problems will be over," and I value Austen so, so highly for disappointing me on that front, and with such skill. She writes disappointment so beautifully.

Who can be satisfied with Edmund? And who can be satisfied with Edmund after such a short, offscreen change of heart, such a truncated proposal? He's the Ann Veal of Jane Austen: "Her?"

And I’m including here an extended conversation with Margaret, about her aims for the course and the idea of “adaptation as empathy,” to give you a better sense of what the course will cover:

LAVERY: Tell me more about "adaptation as empathy"! Is it at all connected to MP being one of the least-frequently adapted works?

WILLISON: I chose to pair Mansfield Park with my “adaptation as empathy” framework more because I think the text demands active empathy from the reader to work than because of how often it has, or has not, been adapted.

I first designed the framework for my 2021 class on Emma, which is not just one of Austen’s most adapted works, but also the source text for Clueless, the most successful modernization of any of Austen’s novels. So, going into that class, I knew that adaptation was going to be one of my primary foci, and I struck the idea of using adaptation to develop empathy because of how divisive the character of Emma Woodhouse is. One of the incredible strengths of that novel is that if you love Emma, you’re right, and if you hate Emma, you’re also right; she is a genuinely ambivalent character.

However, I find when we read books for pleasure, many of us default to our natural allegiances – charming dilettantes relax into their identification with Emma, conscientious hand-wringers indulge their sense of affront, and both sides miss out on the real treat, which is the tension of feeling simultaneously charmed and affronted by Emma. It’s like a really great yoga pose for your brain. To encourage my students to revel in that tension, I had them think about the choices artists make when adapting an existing work, and then replicate those choices with the explicit goal of creating scenarios that would challenge their natural allegiances.The results were more impressive than I could have imagined– I was made to feel true sympathy for the character of Frank Churchill multiple times, something I would not not have thought possible prior to the class.

That’s the magic I wanted to bring to this reading of Mansfield Park, where the characters are not so much divisive as they are deliberately unsatisfying. There is almost no way to read it and experience the relaxation of a natural allegiance indulged. The charming dilettantes who see themselves in Mary and Henry Crawford must confront how leading with charm corrodes your integrity. Meanwhile, the conscientious hand-wringers are stuck identifying with Fanny and Edmund who, to paraphrase Pride and Prejudice, have just enough merit between them to make one morally strong character– Edmund has all the strength, and Fanny all the durable moral insight. Like you, I love the honest realism of these flawed characters and I am hoping the adaption exercises help all of us take strength from the truth of their depictions despite the frustrating muddle of a world it creates.

LAVERY: What's your own relationship to the book? Do you think of Mansfield Park as misunderstood, or is it low on your own list, and you're looking to see what you can make yourself appreciate?

WILLISON: The first time I read Mansfield Park as a teenager, I felt all the frustration it still provokes in me but none of the admiration for its honesty I now have. I found it so frustrating that I actually wrote my senior research paper about how the absence of dynamism in Fanny’s character results in a fundamentally unsatisfying story. Now, mere months shy of my 40th birthday, I like to think I have a healthy distrust of narrative satisfaction. Life is rarely anything other than a fundamentally unsatisfying story. I think the majority of our narratives about moral people focus on the righteous exceptions, people like Joan of Arc who must make their divine certainty manifest in a world hostile to it. But most moral people are actually like Edmund and Fanny– imbued with confidence only when their morals affirm established power structures and forced to muddle through being a fucking bummer when their morals instead demand they act against prevailing norms.

As grandiose as it sounds, I think much of The State Of The World Today is due to narrative seduction– everyone wants a story where they can be Joan of Arc, but the work we actually have to do to improve things is Fanny Price shit. When one side of the political spectrum lets everyone imagine themselves an avenging hero and the other side, when it’s even trying to live out its morals, must instead demand we all sit in a room and calmly talk through issues our limbic systems wish only to scream about, well. It’s easy to see how one side rapidly gains the upper hand. I cannot lie and say anyone who comes to this class gets to leave feeling like Joan of Arc. But I do hope that examining this narrative right now can help us adjust the scale and rediscover the genuine moral strength required to be a wet blanket. The world is on fire! Wet blankets are highly needed right now!

LAVERY: Which of the Crawfords would most easily charm you out of your principles?

WILLISON: Oh, Mary, without a doubt. Henry’s charm comes from his complete belief in his own bullshit. There’s incredible seduction in the purity of attention such belief can enable, but I have lived long enough to know how it dissolves like cotton candy on your tongue the second you, too, come to believe in it. Mary, on the other hand, charms from strategic necessity. As a fellow charmer, I would find the self-aware schemer beneath the charm so much more disarming, and I would be so much more apt to believe I was the lone confidant trusted behind her curtain, the only one smart enough to see her game. And, as anyone who’s ever watched a con man movie knows, that’s the moment you belief your relationship with the con artist is singular is the moment you’ve become their mark.

LAVERY: And what's your relationship to priggishness? I think it's a book that makes us take our fear of priggishness seriously. I couldn't do that very well when I first read it in college, but I'm less afraid of it now.

WILLISON: I think I accidentally answered this one already in talking about my relationship with Mansfield Park, but that’s okay because I went SO LONG in explaining “adaptation as empathy” that a longer answer here would be unduly taxing to your readers’ attention.

LAVERY: What would be the best-case outcome for this course? What's the absolute best thing it could give students that they might not have had before when it comes to Austen and to MP in particular?

WILLISON: I would love people to come away with some of my hard-won love for Messy Austen. Charlotte Bronte said of Pride and Prejudice “I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen in their elegant but confined houses,” but that is exactly what reading Austen made me long for when I first fell for her books as a teenager. Georgette Heyer and the entire genre of Regency Romances suggest I am far from alone in finding Austen’s carefully-fenced, highly cultivated garden so seductive. As a result, I think many readers are too quick to discard her more unwieldy books like Mansfield Park and Northanger Abbey– because they do not offer the pleasures we have come to expect from Austen, we can overlook the unique pleasures their refusal to conform generate. I want this to be a space where people really connect with that, and where they get to do so with others as ready to discover these joys.

MARY CRAWFORD: What is Fanny Price’s deal

Fanny Price small monkey or homunculus

Fanny Price enchanted doll gift of human appearance?

Fanny Price normal

Can Fanny Price go outside

How to lie to make Edmund like you

I enjoy reading Mansfield Park, although honestly, it's been a while. I do like Fanny and appreciate her bravery in rejecting Crawford. But I think one of the reasons I do like her is that I hate Mrs. Norris so much. Austen created such a moral monster in her. I've never seen a good adaptation that takes Fanny's character seriously. The BBC one from the 1980s is the most true to the book, but I found the actress who played Fanny excruciatingly awkward and mannered. Love to see someone take the novel on and make a strong adaptation that doesn't turn Fanny into Jane Austen.

Cannot wait!